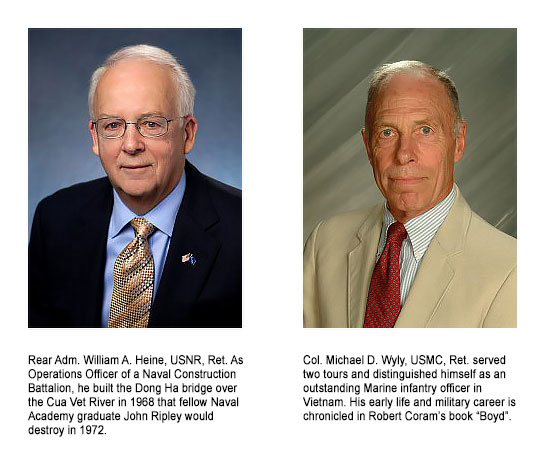

Review of An American Knight by Rear Admiral William A. Heine, USNR, Retired and Colonel Michael D. Wyly, USMC, Retired. Both men were classmates of Colonel John Ripley, Class of 1962, U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis.

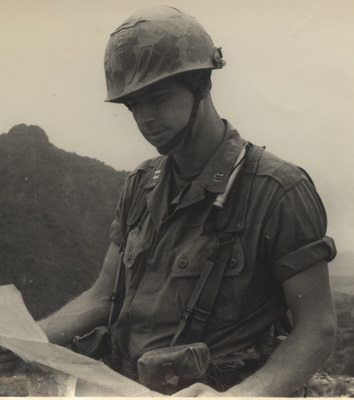

A lone U.S. Marine hand-walked, gripping the girders underneath the bridge over the Cua Viet River in the midst of a fire fight, on Easter Sunday, 1972. South of the bridge, a beleaguered battalion of fewer than 700 South Vietnamese Marines was the last ditch defense of the town of Dong Ha. North of the bridge, a column of 200 Soviet-built tanks and 30,000 North Vietnamese soldiers moved south.

The bridge was their destination and their means of rapidly reinforcing the communist forces already in the Republic of Vietnam. As advisor to the South Vietnamese battalion, Captain John W. Ripley, received the order to destroy the bridge. He did so, single-handedly.

It would take him three hours hand-walking out with the explosives and back again for more. At one point he passed out from fatigue on a girder, only to be awakened when a round from the main gun of an enemy tank slammed into the bridge and jolted him awake. “‘The idea that I would be able to even finish the job before the enemy got me was ludicrous,’ Captain Ripley is quoted. ‘When you know you’re not going to make it, a wonderful thing happens: You stop being cluttered by the feeling that you’re going to survive.’”

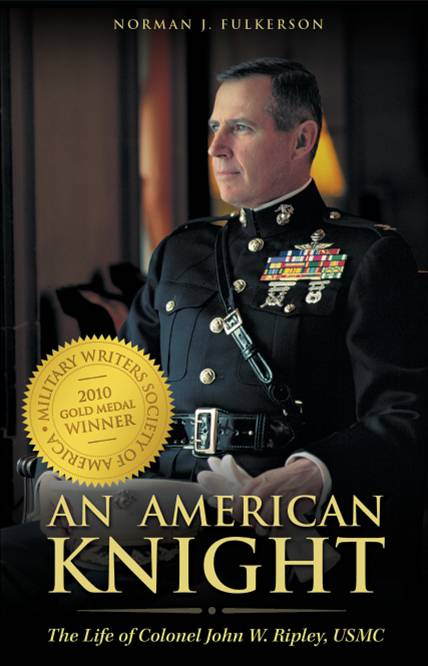

The captain would retire from the Corps as a full colonel in 1992. The writers of this review have known him since we were all 18-year-old plebes reporting to the U.S. Naval Academy in the Class of 1962. “Rip” as we called him died of an apparent heart attack in October 2008 and we each had conversation with him within a week of his death, knew him in the course of our own military careers, knew he was the hero who single-handedly destroyed the bridge, but did not know how much a hero, had never heard Rip’s words quoted above, until we read Norman Fulkerson’s An American Knight. If you understand the title, you do not need to read the book. But read it anyway. It is an uplifting story.

From Fulkerson we also learn that when asked to sign a contract for a possible movie about his actions, Rip imposed two conditions. Whoever portrayed him would not use profanity and would not be unfaithful to his wife.

When it came to being an officer of Marines, Rip epitomized what this means in a way Hollywood might never understand.

Simply put, Rip was a gentleman.

Hollywood images of tough guys swearing and womanizing may attract throngs of ticket-buyers seeking an evening’s entertainment, but they fail to capture what service to one’s country and courage under fire really are. John captured them both, true to life.

Fulkerson’s writing style is without pretense. One editor described the book as “an easy read.” It follows the chronology of Colonel Ripley’s life in sequence. No flashbacks or fast forwards. We meet his parents and the small town Radford, Virginia, where he grew up. We meet his bride to be and learn of his courtship and marriage. But without the author having to tell us, we sense where the story is taking us, that when Rip is called upon, he will do his duty, no matter the odds.

And so it was with we who knew him. When we were all teenage midshipmen Rip’s future had an inevitability about it. That he would be a Marine officer was a certainty. On this, he was thoroughly focused. Likewise, that he would stay in uniform for a full 30 years. That his specialty would be infantry.

Our images of military life were formed in World War II. “Marine” meant hitting the beach in a landing craft with a drop-ramp bow and charging on foot against the enemy. That we would one day go to war to fight for our freedom seemed equally certain. Rip wanted to do that because he believed in what the country stood for. Add all this together and you knew Rip would be called upon to do his duty, to exercise immense courage under fire, and that he would rise to the occasion, never flinching. And with that ever-present broad smile on his face.

Rip had two tours of duty in Vietnam, the first as an infantry company commander. Here we read of his forbidding his Marines to shoot a pig because “it belongs to a farmer who needs to sustain a family.” And the same humanitarian thread continues as the bridge at Dong Ha finally blows into “massive chunks of concrete and steel spiraling through the air” while Rip holds in his arms a Vietnamese child whom he rescued from the impact area just in time.

Rip’s story does not end when the bridge blows up. As a colonel he is assigned back to his Alma Mater at Annapolis. There, he sets an example to the young midshipmen in his charge, guides and mentors them, earning respect and love above and beyond anything we remember witnessing or hearing about in our own careers. His calm manner, his inner toughness, and his ready smile—all life-long traits—made it a morale boost just to be in the same room with him.

Norman Fulkerson first met Colonel Ripley in 1993 when the Colonel delivered a speech for the launching of the book Nobility and Analogous Traditional Elites in the Allocutions of Pius XII at The Mayflower Hotel, Washington, D.C. In the ensuing years he kept in touch, personally, and read articles and books recounting the Colonel’s actions at Dong Ha, Vietnam, in 1972. He met Marines who had served with Colonel Ripley.

The more the author learned of “Colonel Ripley the man,” the more he found himself thinking what a model citizen and model officer the colonel was. Finally, in 2007, a year before Colonel Ripley died unexpectedly, Mr. Fulkerson began to conceptualize a book about the Colonel’s life. The material in An American Knight is drawn from a combination of conversations with Colonel Ripley; meetings and interviews with Marines and family members: several books and articles that have documented the Colonel’s courage in Vietnam, and the content of Colonel Ripley’s speeches that the author had attended over the years.

An American Knight is more than sound military history. It is the story of a life led without pretense or affectation, an example of doing one’s duty selflessly, and, in this way is a story the youth of our country are starved for. Adults should read it for inspiration of how to rear their children and our children should read it to learn that great things can be done by people who come from the simplest beginnings, that bravado is not a requirement, that honor is sacred, and that modesty and courtesy are the keys to respectability. We should hope our grandchildren will put the book down and reflect, “Maybe I could do that” and know, when they too are called upon to act in some unforeseeable situation, “there was one who went before me and rose to the occasion. I can too.”