The modern “center-left” position contains a fatal flaw. It cannot prevent its ideas from being used to inspire even more radical modes of thinking. This tendency expressed itself as French liberalism degenerated into the “anti-infallibilist” movement of the late nineteenth century.

Before the First Vatican Council convened in 1869, French Catholic liberal leaders published a manifesto in the French newspaper Le Correspondant opposing Ultramontane theses, especially the definition of Papal infallibility. Its sole pretext was that the time for such a pronouncement was not opportune. These liberals came to be labeled as “opportunists.”

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

That publication gave hidden opponents of papal infallibility a workable formula to fight against the definition without colliding with Catholic doctrine head-on. Once again, the skillful Bishop Felix Dupanloup of Orléans had found the means to maintain Catholic liberalism’s untenable positions. Those involved generally understood the bishop’s tactic. His followers at the Vatican Council rallied under the banner of untimeliness.

Although his orientation was obviously workable, Bishop Dupanloup could not impose it on more liberal Catholics. Soon, a small but radical anti-infallibilist group, largely German, noisily proclaimed its more extreme position. However, it is surprising that these opponents appeared in such small numbers, as liberal dogmas and methods loathe infallibility.

The liberal Catholics’ goal was, and is, to reconcile the Church with the modern world. To attain this end, liberal Catholics adopt the infiltration of institutions and environments as their only form of apostolate. The goal, they say, is to enlighten, dominate, and convert people to Catholicism. Liberals strive to adapt to the dominant ideas in the target environment. Therefore, each country presents Catholic liberalism with slightly different nuances and characteristic features. However, liberal Catholicism’s fundamental tenets and processes are the same everywhere.

For example, nineteenth-century England was entirely dominated by the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. This influence modeled English society on the worldly ideals of Protestant culture. Liberal Catholics adopted this mentality and formed a type of Catholicism that Henry Cardinal Manning characterized as “watered down, patristic and literary.” As a proponent of an admirably strong Catholicism entirely devoted to Rome, he opposed it.

But there was not always someone like Manning leading a vigorous Ultramontane movement working to prevent Catholic liberalism from reaching its ultimate consequences. In some places, like Germany, nothing stood in the way of liberalism’s development in an ever-more radical direction.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Liberal Catholics were living contradictions, professing in practice what they denied in principle. They defended untenable positions condemned by the Holy See. Their inconsistencies forced them to hide behind the distinction between thesis and hypothesis. Since contradiction never imposes itself, their dangerous infiltration tactics were fatal for them. They ended up being dominated by those they sought to convert. Their increasingly diluted brand of Catholicism could not maintain itself in the environments they infiltrated.

This natural consequence was especially apparent in Germany. German universities were dominated by a veritable scientific mania, eminently erudite, guided solely by blind worship of reason. Liberal Catholic leaders, the vast majority of whom were university professors, were carried away by the illusions of their Protestant colleagues. Disregarding the traditional methods of theological study, they created the so-called historical theology. They proudly fought against Thomism, then reemerging in Italy. They refused to accept any authority beyond that of their peers. They denied the Pope’s right to judge their opinions. They claimed to have reexamined all of the traditions of theological knowledge. They rejected everything that failed to conform to their new humanist standard.

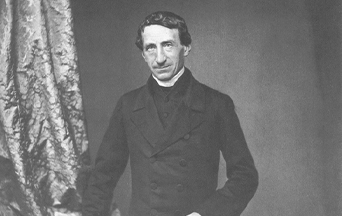

Ignaz Döllinger, a priest and professor at the University of Munich, was the undisputed leader of this movement. Döllinger was a former Ultramontane. He was also a friend of Bishop Dupanloup, with whom he corresponded assiduously. Additionally he also had once taught Lord Acton, the English liberal Catholic leader. He proclaimed himself the judge of the Church’s actions throughout history. Thus, Döllinger is the prototype of a proud and intolerant scientist. Emile Ollivier, who knew him, described him thus: “His face is strong and grave; his gaze has the cold limpidity and impassive penetration of a collector of ideas and facts; and his lips’ ironic rictus excludes all passion other than science.”

Döllinger rejected Bishop Dupanloup’s careful guidance despite his friendship with the bishop and the fact that both served the same cause. He was irritated and insulted by Giacomo Cardinal Antonelli’s1 refusal to name him as a consultant to the Council’s preparatory commission. He wrote a series of articles in the Allgemeine Zeitung, later published under the pseudonym Janus2 in a volume titled The Pope and the Council. Döllinger denied papal infallibility outright and presented all kinds of novel and twisted historical arguments. His passion even led him to falsify texts, as Cardinal Hergenroether proved in his book Anti-Janus, refuting the Munich professor’s errors.

10 Razones Por las Cuales el “Matrimonio” Homosexual es Dañino y tiene que Ser Desaprobado

Döllinger was the spokesman for German liberal Catholics, who held more or less the same opinions as he did. His prestige also impressed liberal Catholics in other countries. Even French academics paid attention, and this weakened Bishop Dupanloup’s party. Thus, an anti-infallibilist current emerged alongside the opportunists. Although allied, their differences caused no little embarrassment to Bishop Dupanloup et al. This infighting undermined the subtle game of distinctions and sleights-of-hand to which this minority had to resort in order to wreak havoc before, during, and after the Vatican Council.

These three positions on infallibility—infallibilists, anti-infallibilists, and opportunists—characterized divisions among Catholics during the controversy preceding the Council. Allied, the last two fought the defenders of orthodoxy uncompromisingly and without the slightest charity.

Footnotes

- Giacomo Cardinal Antonelli was Pope Pius IX’s Secretary of State from 1848 until his death in 1876.

- Janus is the Roman god of time, beginnings and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces, one looking to the future and the other contemplating the past. His name is incorporated into the title given to the first month of the year, January.