We were recently asked to comment on the fact that the custom of granting awards to the best students is being abolished in several schools. At the root of this new policy is the idea that the public bestowal of awards is doubly harmful: exciting vanity in the beneficiaries of the honors and provoking feelings of guilt or inferiority complexes in the others.

Thus, we decided to discuss how this theme vitally concerns the maintenance of sanity in ambiences, develops an appreciation for time-honored customs, and is essential for the life of a civilization.

This problem far transcends scholastic environments, touching directly upon honors and punishments in all human societies.

According to the doctrine of Saint Thomas, the fact that a person possesses authentic qualities and is recognized and honored for them by society is a good that surpasses health or riches, being inferior only to the grace of God, which transcends every other good (cf. Summa Theologica, II-II, q. 29, a. 1; II-II, q. 129, a. 3).

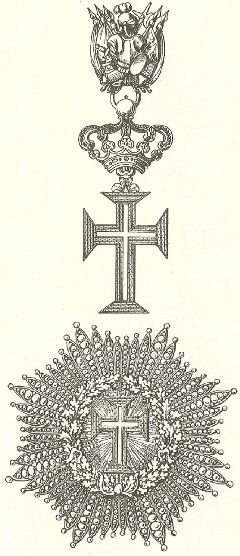

Order of Christ.

Thus, to deprive the best of their rightful honors is a flagrant injustice because it inflicts injury, and a most grave injury, precisely upon those who deserve the contrary.

Moreover, the awarding of honors does not make truly virtuous men proud, but stimulates them to advance farther in virtue. As for the others, it does not degrade them; rather, it invites them to a laudable imitation.

This was taught by Saint Pius X in the brief Multum ad excitandos of February 7, 1905, concerning the Supreme Order of Soldiers of Our Lord Jesus Christ, usually called the Order of Christ. This is the highest honorific Order of the Holy See, and, therefore, of all Christendom. He said:

“Rewards granted for merit contribute tremendously toward stirring in hearts the desire to practice generous acts, for if singularly deserving men of Church or society are vested with glory, they serve as a stimulus for all others to follow the same path to glory and honor. Following this wise principle, the Roman Pontiffs, our Predecessors, looked upon the knightly orders with special affection as another such stimulus to good. Through their initiative, many orders were created; others that had been previously instituted were restored to their original dignity and endowed with new and greater privileges.”

In this spirit, Holy Mother Church established various honors to stimulate the laity. She also provided a variety of honorific titles to reward her priests, of which the titles of monsignor and honorary canon are characteristic examples.

In this same spirit, the Church established ceremonies suitable for inflicting a note of disgrace upon those deserving of it. We need only mention the terrible ritual of

demotion of priests, or, in the Middle Ages, the analogous ceremony for knights who were deemed unworthy of the title.

Our first picture shows the medal denoting singular rank in the Order of Christ. Everything about it—its form, its color, the fact that it is to be worn openly on the chest—indicates the Church’s intention that it be visible to all and thus loudly proclaim the merits of its bearer.

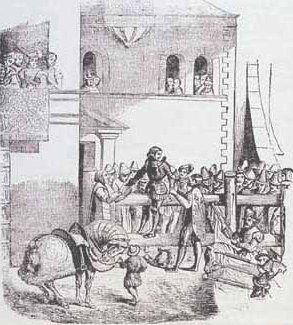

The other picture, a woodcut from 1565, shows a knight being demoted. Knighthood was a sacramental. Thus, the demotion of a knight was done not only with the intervention of the Church, but with her full approval. The picture shows a knight who dishonored his rank by some infamous crime mounted with derision

on the cross-beam of a fence, as if on a wooden horse. To one side, a page holds his charger, which he has been compelled to dismount. The ceremony is half-over. The knight has already been divested of his helmet and gauntlets, which lie cast on the ground.

Two knights in ceremonial attire are now removing his brassards; in such manner, piece by piece, he will be stripped of all his armor. Gathered in the place of execution or at nearby windows, the public attends the ceremony, at once horrified and edified by it.

Reminiscences from days of yore, one might say. No. That ceremony, unfortunately secularized, still exists in all modern armies in the form of military demotion. And, even today, the Holy Church punishes infamy for the great benefit of defense of public morality, just as it also constantly and maternally confers honors upon deserving laymen and clergymen. The bestowal of honors is so well known and frequent that examples are superfluous.

As for the application of punishments for infamy, the Colombian magazine El Catolicismo (April 25, 1958), furnishes an example in the discreet words of the Cardinal Archbishop of Bogota, the essence of which is contained in the following paragraphs:

We, Crisanto Luque, Cardinal priest of the Holy Roman Church, titular of Saints Cosmas and Damian, by the grace of God and by the Apostolic Holy See, Archbishop of Bogota and Primate of Colombia,

Considering:

First, that Canon 2356 of the Code of Canon Law so disposes that bigamists…are ipso facto infamous, and, if they disregard the admonitions of the Ordinary and remain in their unlawful relationship, they should be excommunicated or punished with a personal interdict depending upon the gravity of their fault….

That by means of public documents, it was proven that Dr. Hernando Diaz Rubio and Mrs. Olga Pardo Pardo contracted between themselves a so-called civil marriage in Ibarra, Ecuador…, Dr. Diaz Rubio being bound by a previous marriage yet knowing intimately Mrs. Pardo Pardo;

We thus declare:

First, by the very fact of having ventured to contract this so-called civil matrimony, they are infamous and are subject to all canonical consequences of infamy by law…(Canons 2356 and 2294, sec. 1, Code of Canon Law);

This decree notifies the guilty parties and reminds them of their duty to separate under threat of being excommunicated if they remain in their unlawful relationship, and it is published by the press so that it might produce the desired social effects.

In short, to confer public awards and inflict ignominious public punishments conforms to the morals and practices of the Holy Church. In our opinion, any pedagogical method that denies this cannot be considered effective, much less inspired.

This article was originally published in Catolicismo, January 1959