Photo Credit: Walters Art Museum, CC BY-SA 3.0.

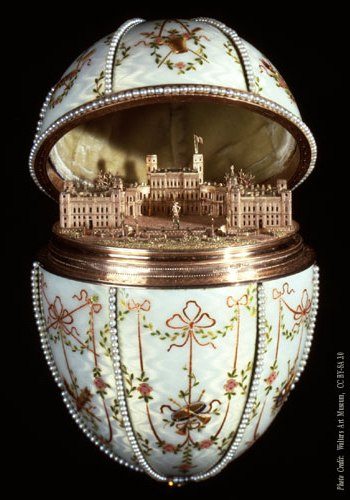

What’s small, white, oval, and has a miniature replica of the Russian Gatchina Palace inside? You’re not mistaken if you initially thought of an egg. Of course, the Gatchina Palace Fabergé Egg isn’t your average grade A large white egg that you would buy in a carton at the supermarket. Fabergé Eggs are anything but average. They are, in a word, sublime.

The egg in question was made by Mikhail Perkhin in 1901 for Tsar Nicholas II, who gave it to his mother, the dowager empress Marie Fedorovna, as an Easter present. Mikhail Perkhin was a workmaster in the House of Fabergé, the jewelry firm started by Gustav Fabergé, a German jeweler who settled in St. Petersburg. It was Gustav’s son, Peter Carl Fabergé, who was the initial creator of the highly celebrated Fabergé Eggs.

Defining the Sublime

According to Sir Edmund Burke, “the sublime is the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.” In his book Return to Order, John Horvat II defines the sublime as: “those things of transcendent excellence that cause souls to be overawed by their magnificence.” These are moments when panoramas, works of art, architecture or even excellent cuisine provoke a jaw-dropping and enthusiastic “Wow!” to escape from our lips. A Fabergé Egg provokes the same reaction.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

The detail of the Gatchina Palace egg is stunning. At a mere three inches tall, the cannons, windows, trees and flag of the palace are clearly distinguishable. The exterior of the egg is skillfully crafted of gold, enamel, silver-gilt, diamonds, rock crystal, and seed pearls. These precious materials are individually treasured, but using them together to create a single object makes them priceless. However, what makes the Fabergé Egg so valuable is not the monetary price of the materials, but the skill and mastery of craftsmanship used to create it.

The Sublime: A Fruit of Christian Civilization

Why make something so precious in the form of an egg? The answer is simple: this is a fruit of Christian civilization. Civilization works precisely in this manner. It takes that which is ordinary and makes it extraordinary. Civilization uplifts and elevates even the most common and practical aspects of life. In the Middle Ages, Christian civilization flourished throughout Europe, and gave rise to the establishment of universities, the construction of grandiose cathedrals and the end of slavery. It goes to show that, because of Christian civilization, even a form as plain as an egg can be made into a treasure worthy of a king.

History of the Fabergé Eggs

The custom of gifting an enameled Easter egg to the dowager empress Marie Fedorovna was started by her husband Tsar Alexander III in 1885. Although the reason why Alexander III started giving the jeweled eggs to his wife at Easter is unclear, it is a fitting present in relation to an ancient Easter tradition. Early Christians celebrated Easter by giving presents of colored eggs to one another. The symbolism was threefold. Eggs dyed red represented the blood Our Lord had shed. It was also part of the Lenten fast to abstain from eating eggs. Lastly, when the egg shell was cracked open and left empty, it symbolized the empty tomb following Jesus’ resurrection. This custom continued through history and became a widely practiced tradition in Russia and Europe. The Fabergé Egg could be called the culmination of the Easter egg tradition. It is the apotheosis of the Easter egg.

The first commission Peter Carl Fabergé received was for the Hen Egg. Like a Russian nesting doll, it contained a spherical gold yolk that enclosed a jeweled hen, which in turn opened upon a minute diamond replica of the imperial crown from which a small ruby pendant hung. The empress was so enamored by the egg that Tsar Alexander bestowed the title “goldsmith by special appointment to the Imperial Crown” on Peter Fabergé, and from thenceforth commissioned him to make a new egg every year. Tsar Alexander entrusted the design of future eggs to Fabergé, so long as each one was unique and contained a surprise. After Alexander III’s death, his son, Tsar Nicholas II, continued the custom by presenting an egg to both his mother, the dowager empress Marie Fedorovna, and his wife Alexandra Fedorovna.