Religious persecution is a frequent topic of discussion in our country and for good reason. The mere mention of Kim Davis or the Little Sisters of the Poor, is sufficient to conjure up images of a heavy-handed bureaucracy and unjust laws that brook no restraint. Upholding one’s Christian beliefs on polarizing issues such as evolution, global warming, “gender identity” and most especially homosexual “marriage,” can today destroy a man’s career, ruin his business, and perhaps worst of all, make him a social outcast. Not even a diligent county clerk in a backwoods corner of Kentucky or an exemplary order of nuns, who care for the poor, are exempt from harassment. All that is necessary to bring down the wrath of the state—and sometimes even one’s neighbor and fellow church members—upon you is to uphold anti-secularist principles.

Religious persecution is a frequent topic of discussion in our country and for good reason. The mere mention of Kim Davis or the Little Sisters of the Poor, is sufficient to conjure up images of a heavy-handed bureaucracy and unjust laws that brook no restraint. Upholding one’s Christian beliefs on polarizing issues such as evolution, global warming, “gender identity” and most especially homosexual “marriage,” can today destroy a man’s career, ruin his business, and perhaps worst of all, make him a social outcast. Not even a diligent county clerk in a backwoods corner of Kentucky or an exemplary order of nuns, who care for the poor, are exempt from harassment. All that is necessary to bring down the wrath of the state—and sometimes even one’s neighbor and fellow church members—upon you is to uphold anti-secularist principles.

In the face of such persecution, an individual has two options. He can either speak up or conveniently stay in his comfort zone. This alternative is not unique. It is exactly what early Christians faced. Their example should inspire us, most especially American men, to stand firm.

“Death to the Atheists, Search Out Polycarp”

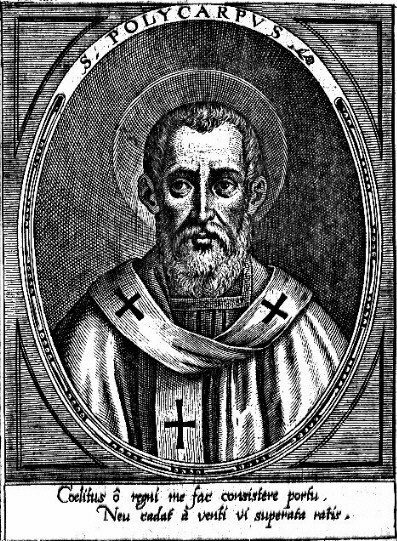

The first three centuries of the nascent Church, as told by Jacques Zeiller in his book Christian Beginnings, is truly the most dramatic period in Church history. All of the Apostles, with the exception of Saint John, followed the heroic example of Our Lord. They defiantly denounced error, defended the truth with fiery zeal and courageously gave their lives rather than concede one “jot or tittle” of Divine Law. Before giving the ultimate testimony of their Faith, however, these indomitable men passed on that same unwavering Faith with its precepts, to four men whom history refers to as the Apostolic Fathers. One of the greatest of these was Saint Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna.

He was preceded in death by Saint Germanicus. As this young man stood in the arena, heroically waiting to be devoured by lions, a proconsul pleaded with him to deny his Faith in order to obtain pardon. The youthful Germanicus not only refused his offer, but provoked a hesitant beast in the arena by slapping it. Whereas the raucous Roman spectators were impressed by this, they cried for yet more Christian blood. They looked upon those who did not worship the false gods as heathens and, desiring the death of the most ardent Christian of the time, they clamored, “Death to the Atheists, Search out Polycarp.”1

“I Will Put You to Death By Fire”

Saint Polycarp was not alarmed at the bloodshed and remained in the city. While praying for his flock, he saw—in a vision—his pillow go up in flames and recognized it as a sign. He calmly turned to his friends and said, “I will be burned alive.” It was very fitting that he, being the last link with the Apostles who walked with Our Lord would die in a Christ-like way. He, like our Savior, was betrayed by one of his servants and when soldiers arrived, he asked only for an hour to pray in his own “garden of olives.”

When his turn came to enter the arena of execution, a voice from heaven was heard: “Courage, Polycarp, play the man.” In modern terms it would be the equivalent of saying, “man-up” and that is exactly what this paladin of virtue did. The same frenzied crowd, which had witnessed the death of Saint Germanicus, now screamed with delight at the sight of this holy bishop. With a look of gravity on his face, Saint Polycarp pointed his finger at the godless masses, then raised his eyes to heaven and said, “Down with the atheists.” For this act of defiance, the proconsul threatened to turn the lions on him if he failed to insult Christ.

“I have served Him for 86 years,” Saint Polycarp replied, “and He has never done me wrong. Why then should I blaspheme my King and Savior?” Seeing him scorn the beast in such a way the proconsul responded, “I will put you to death by fire.”

Death of Polycarp

“You threaten me with a fire which burns for a time and then goes out,” the saint replied. But do you know the fire of the judgment to come, which will devour the wicked? Come now, waste no more time.” It was a more eloquent way of saying “bring it on.”

The fire thus set, eventually encompassed the saint but to the amazement of the crowd it did not touch his body but rather formed a vault around him. His flesh was not consumed, but rather, like a loaf of bread, turned brown or transformed as gold in the crucible. Nor was there a foul odor. On the contrary, eyewitnesses recounted the smell of a delicious aroma, like incense or precious spices. Fearful of the impact such an edifying scene might cause on this pagan audience, an executioner leaped forward and plunged his sword into the saint’s body causing an even more extraordinary occurrence. From the gapping wound flew a dove and such a quantity of blood that the fire was completely extinguished.

After his death, the persecutions did not end. However, they became even more violent under the Emperor Trajan Decius who desired the ultimate extermination of Christianity. He imposed an act of adherence to pagan worship and reverence to the emperor’s statue. Those who offered incense were given a certificate called a libellus.2 Those who refused met the same glorious fate as Saint Polycarp.

Over the next century, persecutions waxed and waned while the Church grew in number and fervor. Thus the Faith unleashed by Our Lord continued to spread like an unchecked tidal wave and forced unjust rulers to change tactics.

“They Wanted Apostates, Not Martyrs”

Those who carried out the merciless slaughter quickly learned how the blood of the martyrs truly is the seed of new faith. From the blood-soaked soil of the first centuries a wellspring of even more fervent Christians sprang up; emboldened by the examples of those who had gone before them. Thus, the magistrates of the time became less anxious to punish defiance than to obtain adherence to false gods and an obnoxious religion.

The early Christian theologian Origen said it best. The judges of the time, he reasoned, might have been upset to see the followers of Christ face death with such soul-stirring courage, “but their joy was boundless when they were able to triumph over a Christian.” Their objective therefore was not to make more martyrs but more apostates.3 And so it is today.

Early Christians Did NOT Live In Catacombs

While the examples of early Christians are inspiring, many speak of martyrdom today as something inevitable. This is dangerous because it can produce, even in well-meaning Catholics, a sheep-like attitude that gives up the fight before it even begins.

This idea gains traction from a fundamental misunderstanding of the time period. Contrary to common opinion, early Christians did not live in those underground cemeteries called “catacombs.”4 While it is true they were forced to celebrate Mass there during times of intense persecution, believers of the time did not hide themselves nor their politically-incorrect beliefs. They spread the Faith through example but also by word and deed. Whereas their exemplary Christian life distinguished them from others in society, it by no means segregated them from it.

This was especially so regarding military service. The Church holds it a duty to defend one’s country in a just war. Whereas the issue of “conscientious objection”5 was raised, it had nothing to do with shedding enemy blood. Rather, it was because the Christian warriors admirably refused to participate in pagan services that were so closely associated with military life of the time. One does not need to use much imagination to surmise what those warriors would say about freely mixing men and women in our American Armed Forces today.

What can we learn from the early Church?

Contemporary Tyrants Want Weak-kneed Apostates, Not Heroes

First of all we are not being asked to obtain a libellus—yet. Nor are we being fed to hungry lions for refusing. The last thing modern-day-“emperors” in the West desire, most especially in America, is a repeat of the soul-stirring examples of faith like Saint Polycarp.6 Like their predecessors in history, contemporary tyrants want weak-kneed apostates, not heroes. Now is not the time, therefore, to seek a fictitious catacomb existence in the comforts of our homes. Nor is it acceptable to give in on a single point of Church teaching so as to be liked by others. Early Christians did not seek the applause, much less the approval, of others. In fact, they shunned those who offered incense to false gods as heretics, while they considered themselves to be among “the few, the happy few.”

What our secularized world needs most today is not sheep, but rather lions who keep always before them the promise of Our Lady at Fatima: Her Immaculate Heart will triumph. It is not the time for romantic dreams of dying peaceably, for Christ; it is time to boldly confront the errors of the day, for Christ. And this must be done with the same firmness of those great saints of old.

It is time to oppose, in peaceful and legal means, the militantly anti-Christian culture. That is our coliseum. It is time for true men to enter that arena, in order to denounce error, defend truth, encourage, inspire and, as Winston Churchill counseled England during hard times, “never give up.” It is time, therefore, for courage. It is time to “play the man!”

Footnotes

- Jacques Zeiller, Christian Beginnings (Hawthorn Books, 1960). The account of Saint Polycarp’s death can be found on pages 57-63.

- From the Latin liber meaning book, but also used to describe a petition.

- Ibid., p. 102.

- Jacques Zeiller, p. 114.

- Ibid., p. 116.

- While we speak of the West, we are not ignorant of the countless Catholics who have suffered martyrdom over the last century in countries dominated by Communism and Islam. We might not know their glorious stories but they are most certainly known to God.