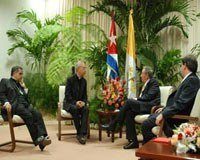

As the Vatican’s Secretary for Relations with States, Archbishop Dominique François Joseph Mamberti has just made an extensive five-day official visit to communist Cuba on June 16-20.

Already on the first day of his stay, the prelate held a joint news conference with the Cuban Foreign Minister in which he welcomed the “ongoing dialogue” with the regime and expressed his hope that dialogue “will be strengthened” by his visit. He optimistically concluded that positive fruits “can already be seen.” However, in his remarks, Archbishop Mamberti refused to include among those “fruits” of the dialogue with the communist regime, meetings with Cuban dissidents and visits to political prisoners. For lack of a better argument, he claimed he was merely carrying out an “official visit.”

In short, the Vatican diplomat was all smiles toward the communist regime while frowning on the opposition and, ultimately, on the enslaved Cuban people.

Among the “fruits,” the high-ranking prelate appeared to include “mediation” with the regime led by the Archbishop of Havana, Cardinal Jaime Lucas Ortega y Alamino, who has a well-known track record as a collaborator of the regime. In fact, the only “fruits” the cardinal seems to have garnered do not go beyond the mere transfer of a dozen sick political prisoners.

These were being tortured in prisons far from their homes but are now being tortured near their homes. He also obtained parole (which is not the same as unconditional release) for Ariel Sigler, a regime opponent who was a famous athlete and is now confined to a wheelchair because of privations and torture. Actually, by releasing him, the regime avoids the risk of having such a well-known political prisoner die in jail and become a martyr.

With his trip, statements and silence, Archbishop Dominique François Joseph Mamberti continued the mysterious, enigmatic and baffling collaborationist ritual of high-ranking Vatican officials who have traveled to the island prison

over the last decades. These range from the infamous Nuncio, Archbishop Cesare Zacchi, who praised the alleged “Christian virtues” of dictator Fidel Castro, to the steps of his predecessor as Secretary for Relations with States, Archbishop Agostino Casaroli, who in 1974 said that Cuban Catholics were “happy,” all the way to the present Secretary of State, Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, a strong proponent of “dialogue” with the regime. In this regard, I have often found myself in the painful need of writing articles which are always well-documented yet never contested.

In fact, we are now witnessing more than “mediation.” This is literally a “rescue” of the Cuban regime on both foreign and domestic levels, driven by the island’s bishops and by Vatican diplomacy. On the foreign level, the European Union is allowing itself to be impressed and stunned by this ecclesiastical “rescue” operation and has thus postponed until September a possible hardening of its stance toward the Cuban dictatorship. Domestically, this “rescue” will demoralize the faithful Catholics of the island and those Cubans who heroically oppose their shepherds’ collaboration with the communist wolves.

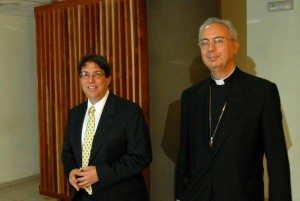

In this regard, the auxiliary bishop of Havana, Most Rev. Juan de Dios Hernández, during the visit by the Vatican envoy, acknowledged that “resistance” can be found among Catholic Cubans to the said rapprochement between clergy and wolves. He took advantage of the occasion to try to anesthetize the consciences of the faithful by claiming that “we must be patient.”

With this diplomatic “bailout,” the Holy See and the Cuban bishops not only benefit and contribute to the survival of the Castro regime, but also help, by the principle of communicating vessels, to strengthen the regimes of Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia and Nicaragua, ostensive allies of communist Cuba.

In so doing, they also encourage revolutionary radical currents in Brazil and other countries in the region acting as Trojan horses. Accordingly, the responsibility of these churchmen before God and History is far from small. Indeed, at stake is the now over fifty-year regime of slavery of twelve million Cubans, the uncertain future of many countries in the region; and the very future of the continent with the world’s largest Catholic population.

Armando Valladares, a former Cuban political prisoner, was U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Commission on Human Rights in Geneva during the Reagan and Bush administrations.