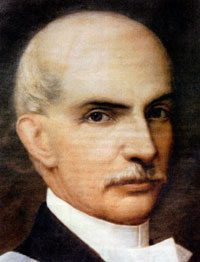

Manly Catholic of intransigent principles, slain by the enemies of the Faith because of his consistency and courage in defense of the Church and Papacy

Gabriel Garcia Moreno was born in Guayaquil, in southern Ecuador on December 24, 1821. His father, Gabriel Garcia Gómez was Spanish, while his mother, Doña Mercedes Moreno, was a member of the local aristocracy. Tragedy visited the family when the father died suddenly in his youth, shortly after losing his fortune. His young widow employed a priest to teach her son his first letters. Later, Gabriel continued his studies at the Colegio de San Fernando in Quito.![]()

FREE e-Book: A Spanish Mystic in Quito

Moved by religious fervor, Garcia Moreno received minor orders in 1838, but became convinced that he did not have a priestly vocation and ended up studying law. After his schooling, Gabriel devoted his life to politics.

He became Commissioner of War in the northern jurisdiction, but in 1846 was involved with some periodicals that were highly critical of Ecuador’s government. Nevertheless, he collaborated with the regime during the threat of invasion by General Flores in 1847. He was an active member of the Municipal Council of Quito and later became Governor of Guayas.

Due to political turmoil, he was exiled in 1848 and traveled to Europe the following year.

When he returned, he dedicated himself to politics once again. In 1853, he successfully lobbied for Ecuador to receive the Jesuits expelled from Colombia.

He soon won a senatorial election, but was exiled a second time before taking his seat. During his deportation, he diligently applied himself to study in France. He worked so hard that his health began to suffer. During this time, he wrote: “I recognize that I have abused my strength and nearly did myself more damage. Neither my head nor my strength are proportional to the energy of my will.”1

Returning, he got involved in the cultural life of the country, where he fulfilled many important functions. In 1857, he was elected mayor of Quito and rector of the local university. Shortly, as a senator, he gained notoriety for his fiery speeches. On April 2, 1861, he became President of Ecuador.

A Providential Mission: Free the Country from Chaos

Originally, Ecuador and Venezuela were part of a larger nation called Great Colombia, which was created by Bolívar in the early 1800s, after the war of independence.

When Great Colombia collapsed in 1830, Ecuador became a nation. Revolutions followed that threw the nation into chaos. Bad government and sectional resentments ravaged the country to such an extent, that the Catholic Church was the only unifying factor in Ecuador.

Garcia Moreno took advantage of this situation to mold the government after the Faith, which was deeply rooted throughout the nation.

His work was difficult because Catholics had been practically orphaned by a lax clergy that often failed in its duties. Seminaries were decadent, religious instruction was wanting and whole sections of the population were left without guidance. Ecuador needed a strong leader. Garcia Moreno was so well suited for this task that even his detractors admit that he was the man Ecuador needed at that critical time.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Historian Calderón García described Garcia Moreno’s character and work as: “Indefatigable, stoic, just, energetic in his decisions, admirably logical in his life, Garcia Moreno is one of the greatest personalities in the history of the Americas.…In fifteen years he completely transformed his little country according to a vast political system that only death prevented him from completing. He was a mystic of the Spanish type, not satisfied with sterile contemplation, he needed action. He was an organizer and a creator.”2

Throughout his entire administration, Church doctrine guided his actions. “His philosophy was inspired in the classical doctrine of Thomism.”3

Resolution of the President: Concordat with the Holy See

When Garcia Moreno assumed the presidency, the Church in Ecuador was beset with insubordination, immorality and laxity, due largely to an abuse of authority that limited the power of the Holy See regarding religious affairs. The president immediately drafted a concordat to correct this abuse.

The document’s first article gives the tonic note of the whole. It stipulates that the Catholic Church would continue to be the State religion and preserve the rights and prerogatives afforded Her by the Law of God and cannon law. All dissident worship was prohibited.

It states: “the instruction of the youth in the universities, high schools, colleges, public and private schools will all be in accordance with the Catholic Religion,”4 because “The Catholic Religion was one of the few bonds of Ecuadorian nationality…Catholicism is a force of political cohesion.”5 Thus, “the fundamental articles [of the concordat] were not attacked, nor were amendments proposed to them.”6

Consecration of Ecuador to the Sacred Heart of Jesus

However, Garcia Moreno’s adhesion to the Faith was not limited to internal affairs. When the Papal States were invaded in 1870, Garcia Moreno was the only ruler in the world to protest. He wrote to the Minister of Foreign Relations of Italy, decrying the Italian government’s robbery of pontifical land.

The grateful Pope sent him a Decoration of the First Class in the Order of Pius IX with a brief commendation, dated March 27, 1871.7

“As a manifestation of solidarity with the Holy See, [Garcia Moreno] decreed in 1873, that the Supreme Pontiff be sent ten percent of the state’s tithes.”8

However, the most symbolic act of Garcia Moreno’s government was the ecclesiastical and civil consecration of the Republic to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. During its ceremonial consummation, the president affirmed: “I recognize the faith of the Ecuadorian people, and that Faith imposes on me the sacred obligation of conserving its deposit intact.”9

Years before, a decree of the Constitutional Convention had declared the Virgin of Mercies Patroness of Ecuador.

Assassinated for His Devotion to the Catholic Faith

This government, led by the religious fervor of its president, worried the Masonic sects, which immediately began planning his assassination.

Perhaps Garcia Moreno foresaw his demise. During this time, he wrote to Pius IX: “What a treasure it is for me Holy Father, to be hated and calumniated for my love for Our Divine Redeemer. What happiness, if your blessing were to obtain for me from Heaven the grace of shedding my blood for Him, Who, being God, willed to shed His Blood for us on the Cross!”10

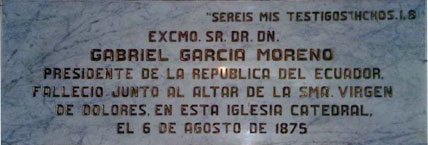

On August 6, 1875, Garcia Moreno entered the Cathedral to make a visit to the Blessed Sacrament. Conspirators interrupted his prayer to tell him he was urgently needed next door at the presidential palace.

Garcia Moreno immediately left the Church. While climbing the steps in front of the palace, a ruffian named Royo struck him in the back of the head with a machete, crying out: “death to the tyrant!” He then almost hacked off the president’s arms as he tried to fend off his assassin’s blows. Meanwhile, three accomplices shot him in the chest.

Mortally wounded, Garcia Moreno was then thrown down onto the plaza, where Royo struck him several more times on the head. While agonizing, he managed to wet his finger in his own blood and write on the ground: “Dios no muere” (God does not die).

He was carried quickly to the Cathedral, where he received Extreme Unction and died.

Learning the sad news, Pius IX declared that Ecuador:

distinguished itself miraculously by the spirit of justice and the unshakable faith of its president, who showed himself always a submissive son of the Church, full of devotion to the Holy See and of zeal to maintain Religion and piety in his whole nation…

So it was, that in the councils of darkness organized by the sects, those villains decreed the assassination of the illustrious President. He fell under the steel of an assassin as a victim of his Faith and of his Christian Charity.11

Footnotes

- Cartas Inéditas. Garcia Moreno to Roberto Ascásubi. Piura, April 20, 1855: in Ricardo Pattée, trans. Cecília F. Vargas, Garcia Moreno e o Equador de seu tempo (Editoria Vozes: Petrópolis, 1956) p. 126.

- Calderón García, Latin America: Its Rise and Progress (London: Unwin) p. 220, in Ricardo Pattée, p. 15.

- Ricardo Pattée, p. 329.

- 3rd article, in Ricardo Pattée, p. 151.

- Belisário Quevedo, Sociologia Política y moral (Quito: Editorial Bolívar) 1932, p. 54, in Ricardo Pattée, p. 152.

- J. Tobar Donoso, La Iglesia Ecuatoriana en el siglo XIX, Vol. I, in Ricardo Pattée, p. 159.

- “El National,” n° 300, October 10, 1873, in Ricardo Pattée, p. 294.

- José Felix Heredia, La Consagración de la República del Ecuador al Sagrado Corazón de Jesús, Quito, Editorial Ecuatoriana, 1935, p, 198; in Ricardo Pattée, p. 295.

- E. MacPherson.

- E. MacPherson.

- The words of Pius IX, in a public audience in Rome, on September 20, 1875, in Gary Potter, Garcia Moreno, Statesman and Martyr, http://www.fisheaters.com/moreno.html.