In the quest for a golden age for workers, few would look beyond free markets in modern times. This position is backed up by economists using the materialistic tools of their trade. Modern statistics, wages, and living standards all point to definite improvements on the part of workers in market economies.

However, many would be surprised to learn that there were pre-modern times when workers enjoyed broad prosperity and rights. Most people are unaware that the Church has long safeguarded and improved the state of workers and all society.

However, many would be skeptical of such claims since they appear to be unsupported by economic data. Moreover, most people are afraid to question evaluations of pre-modern and especially medieval times like that of Thomas Hobbes who described life in those times as “nasty, brutish, and short.” Thus, modern discussion of the medieval economy is often limited to perceptions not facts, skewed judgments not certainties, prejudice not impartiality.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

A Buried Perspective from Oxford

There is economic data to support the claims that workers prospered in medieval times. One place this can be found, regarding England, is in the works of the brilliant nineteenth-century scholar and economist James Edwin Thorold Rogers (1823-1890). Besides his academic career, Prof. Rogers also served as Member of Parliament for several years.

His greatest achievement, however, was his work as professor of political economy at Oxford. He wrote two books analyzing data collected over centuries. Using the economic criteria of his day, he presents an accurate analysis of the past. While his positions were not always popular, no one disputes his erudition and indefatigable research.

In his book, Six Centuries of Work and Wages, Prof. Rogers claims England’s economic history can be ascertained accurately and comprehensively by looking at the kingdom’s public records dating back to the thirteenth century. “No other country possesses such a wealth of public records,” he claimed. The facts he uncovered stand on their own without major interpretation…or misinterpretation.

How a Dark Age Became a Golden Age for the Worker

What Prof. Rogers found in the records was myth-shattering. Although not Catholic himself, his evaluation of England’s Catholic civilization does much to prove the Church’s important role in society. During the three centuries preceding Henry VIII’s rupture with Rome, Prof. Rogers believed the laboring classes were more comfortable and prosperous than any other later period. It was, he claims, a veritable “golden age for English labor.”

“I believe, indeed, that under ordinary circumstances the means of life were more abundant during the Middle Ages than they were under our modern experience,’ he writes. “There was, I am convinced, no extreme poverty.”

A Different Perspective

His works focus on the medieval laboring classes, which he claims were in steady upward ascendance. The wages of a medieval stonemason, for example, were better than those of his nineteenth-century London counterpart. Instead of working fifty-six-hour workweeks, the late medieval worker clearly “worked for only an eight-hour day.”

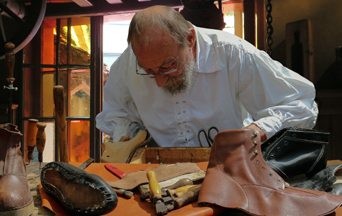

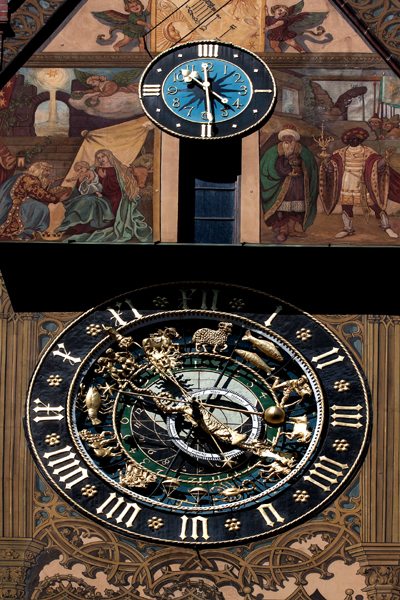

Prof. Rogers describes the institutions and practices that predominated in a prospering society and economy in the time leading up to Henry VIII. Workers were “thriving under their guilds and trade unions,” and there were “peasants gradually acquiring land.” Artisans had great freedom to create works of art found in “handsome churches and conventional buildings of that age.” It was a time of great plenty, that was the fruit of a generous earth and a sturdy yeomanry.

That is not to say England was a paradise without problems. It must also be adapted to the technology and conditions of the time. However, the realm did experience a well-being that is reflected in images of Merry Ole England. Inside a framework of social harmony, the Church provided the safety net and balance that created conditions for prosperity. From Prof. Rogers’ descriptions, one can see that society benefited from the fruits of the Redemption that led men to respect the dignity and worth of all.

The Downfall of this “Golden Age”

The records Prof. Rogers consulted also reveal what led to the downfall of this “golden age.” He claims the turning point was the middle of Henry VIII’s reign. It was then that the search for extravagant pleasures and enjoyment of life led to lavish spending and economic imbalance.

When Henry decided to break with Rome over his divorce, it opened the way for the dissolution of the Catholic monasteries, whose assets he despoiled and then squandered. The high turnover in property ownership and the scramble for riches throughout society led to land speculation and the breakdown of social custom and relationships that had once provided harmony and prosperity to the commonwealth. The Church’s charity that had once provided a safety net for all society was extinguished. The State became an inadequate and cold replacement in caring for the poor, through its workhouses and taxes levied for the support of the destitute.

Destitution and Pauperism

Prof. Rogers notes the period of upheaval led to an alarming growth of extreme poverty, pauperism, and misery that extended even to his day. England never fully recovered from this fall and the workers especially suffered from the loss of the rights and privileges obtained under Christian civilization.

Indeed, numerous historians have related the suffering, poverty, and general decline of morals that followed the dissolution of the monasteries and the suppression of the Church. The great merits of Prof. Rogers’ observations are that they are taken from public records and are told from an economist’s perspective.

His portrayal of medieval economy contrast with the brutish, nasty, and short narrative that more accurately applied to Hobbes’ own Enlightenment times. Prof. Rogers proves that when imbalance and frenetic intemperance enter into an economy, they are highly destructive.

His research demonstrates that the data supports the scholarly claim that conditions of the medieval worker were wholesome and good. Thanks to his studies, one can sustain more solidly than ever that when the passion for justice unites with Christian charity, it provides the conditions for the prosperity of workers and all society.

As seen on The Imaginative Conservative.