The following analysis was written by the Association of the Founders in Brazil, an organization of disciples and followers of Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira and his school of thought and action. In light of recent developments, we feel the following commentary to be especially timely

A reading and analysis of the news over the last weeks clearly shows growing tensions in Latin America, where there is a great political-ideological battle of crucial importance for the future of all countries in the area, particularly Brazil.

Paradoxically, it is in little Honduras where this historic battle is raging most virulently at present.

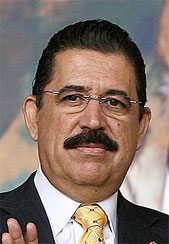

The clandestine return to Honduras of deposed president Manuel Zelaya – an initiative led by Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez – and the subsequent transformation of the Brazilian Embassy into the general headquarters of Zelaya and a group of his closest followers, increased tensions to an incredible degree and caused Brazil to cross an extremely dangerous threshold in international relations.

In an unheard-of gesture totally opposed to the country’s diplomatic traditions, Brazilian diplomats decided to intervene directly in Honduras – violating Honduran sovereignty and disrespecting its institutions and international laws in an unmistakable act of subservience to Chavez’s expansionism.

Facing the gravity of the present situation and inspired with Christian patriotism, the Association of the Founders addresses the public regarding the direction of Brazil’s foreign policy, which is causing growing perplexity and anxiety in countless Brazilians. In so doing, we draw inspiration from the longstanding and consistent action and principles that inspired the eminent and intrepid Catholic thinker and leader, Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira.

I – Fabricating a “Coup d’état” Ghost

There are moments when the international scene is overtaken by some political or religious event which, like a sudden gale, overthrows everything.

Public opinion becomes enveloped in an emotional climate in which well-pondered reflection and balanced judgments are impaired but are nevertheless communicated as undeniable realities.

Honduras, a small country in Central America to which public attention is not habitually turned, has become the epicenter of one of those phenomena. The excuse was the political events that led to the deposition of then president Manuel Zelaya on June 28 of this year.

Torrential news analyses and abundant political reactions lacking impartiality and objectivity insisted that an arbitrary action of political barbarism had been perpetrated against a president legitimately and calmly carrying out the mandate for which he was elected; some even spoke of a return to the “dark times” of military coups d’état.

Led by members of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA), certain Latin American politicians, speaking on behalf of a democracy that many of them deny by their actions, urged a vehement condemnation of the “coup” in Honduras. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva himself joined the chorus condemning the so-called coup.

However, authoritative voices around the world began to point out the true nature of the events in that country. In fact, what had been happening in Honduras was a creeping coup against the institutions of its Constitution led by none other than Manuel Zelaya with the intimate cooperation of Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez.

II – The Truth About Honduras: Zelaya Attacks the Constitution and Challenges the Country’s Institutions

In January 2006, Manuel Zelaya assumed the presidency of Honduras, after winning the election as a member of the conservative-leaning Liberal Party.

Conditioned by an acute crisis in public finances, a fruit of corruption and high oil prices, he began to draw closer to the Venezuelan leader.

Attracted at first by the tempting conditions for buying oil and later by an invitation to join ALBA – which the country did in August 2008 after a sharp dispute in the National Congress — Zelaya reneged on his election platform, announced he was a leftist anti-imperialist, and manifested growing approval of Hugo Chavez’s ongoing maneuvers to destabilize several Latin American countries.

Politically worn out and the object of serious accusations of corruption and connections to drug traffic, Zelaya launched the idea of a plebiscite in March 2009 to reform the Constitution and perpetuate himself in power according to the Chavez book of tricks already successful in Bolivia and Ecuador.

The Honduran Constitution has immutable clauses which include obligatory rotation in the presidency. Breaking that clause is a “crime of treason against the country.” The Constitution also requires immediate cessation of the public mandate (including the presidency) of anyone who proposes or supports a reform of the constitutional provision that prohibits a president from running for a second term.

Indifferent to such constitutional obstacles, President Zelaya issued a decree calling a referendum to establish a Constituent Assembly anyway.

At the end of May, the Court of Administrative Disputes, in a lawsuit filed by the prosecutor and the state attorney general, suspended all practical effects of that decree, deeming it unconstitutional.

The government itself, admitting the illegality of said decree, decided to present a new, slightly modified version, yet riddled with the same defects.

The Superior Electoral Court declared the referendum planned by the executive branch illegal, as well as all preparations for it, particularly for usurping the prerogatives of other branches, which is a felony according to the Honduran Constitution.

At that point, President Manuel Zelaya announced his intention not to respect the decisions of the Judiciary and asked Hugo Chavez to help him organize the referendum. Materials to hold the referendum were brought in from Venezuela.

Zelaya tried one last maneuver by ordering the military to support the referendum, which had been declared illegal. The Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces refused and was summarily dismissed.

On 26 June, the Attorney General asked the Supreme Court for an arrest warrant against Manuel Zelaya on charges of treason, conspiracy against the form of government, abuse of authority and usurpation of his function. The said court ordered the military to arrest Zelaya for those offenses.

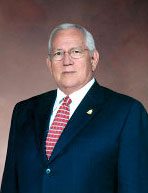

On June 28, Zelaya was arrested and removed from the country. With only five dissenting votes, the Honduran National Congress had Roberto Micheletti sworn in as the new constitutional president of Honduras.

The appointment was consistent with the Honduran Constitution, as the vice president had resigned months earlier to become a candidate in the November elections.

Since an account, however brief, about the institutional crisis in Honduras would be inconvenient for Zelaya, Chavez and their “fellow travelers,” it was necessary to spread the simplistic and partisan idea that the military had carried out a “coup d’état.” Large media conglomerates obligingly spread the “party line.”

In fact, the maneuver calling Manuel Zelaya’s removal a “coup” that must be condemned contained an ideological ruse. By craftily omitting all attacks by Mr. Zelaya against the Honduran constitutional order while claiming to defend it, they also sought to favor the geopolitical strategy of Hugo Chavez and his “twenty-first century socialism.”

As the real facts began to emerge, it became clear that what happened in Honduras was a series of institutional acts to defend the rule of law; and thus the version of an arbitrary action by the military began to crumble.

It should be noted that, despite criticizing the political events, the U.S. State Department never described what happened in Honduras as a coup.

Later, a study by the U.S. Library of Congress – an advisory and non-political consultative organ – deemed the destitution of President Manuel Zelaya constitutional. The study objects only to the legality of his expulsion from the country.

The most relevant document on this point was perhaps the one issued by the Honduras Catholic Conference of Bishops.

In a statement read by Cardinal Oscar Andrés Rodriguez, the Honduran bishops claimed to have sought information from all relevant bodies of the state and civil society and concluded that the decisions that led to the deposition of President Manuel Zelaya were legal and that the state’s democratic institutions remain in full force. The bishops added that they were waiting for an explanation of the expulsion of the former president from the country.

III – Elections and Diplomatic Pressures

Since the deposition of Manuel Zelaya, the government of Roberto Micheletti became the object of countless diplomatic pressures which we will not describe here. However, it is fitting to emphasize the pro-Zelaya orchestration led by the Organization of American States (OAS), under the direction of the socialist, José Miguel Insulza.

Honduras was summarily expelled from the OAS only a few weeks after the latter unconditionally approved the return of the Castro dictatorship to the organization. This is in addition to the OAS’ startling silence regarding Zelaya’s power-encroaching maneuvers and Chávez’s military threats to the country. The OAS was warned by the Honduran Bishops Conference that it should pay more attention to all the illegal things happening before June 28.

Because of its unabashed bias, the OAS became discredited to play any mediating role, which led the parties to hold direct talks under the auspices of the President of Costa Rica, Oscar Arias.

Manuel Zelaya, ignoring his own attacks on the Honduran institutions and his violations of the fundamental law of the country, remained adamant in his demand for a return to power without any conditions, which powerfully contributed to the failure of all attempts at negotiation.

As the diplomatic row stemmed, large demonstrations were held in the streets of Honduras, especially in Tegucigalpa. Hondurans of all walks of life showed the world their opposition to Hugo Chavez’s intervention in their country’s affairs and their ideological refusal of “twenty-first century socialism.”

Facing the failure of negotiations and widespread opposition by the Honduran people to Zelaya’s maneuvers, the November elections in the country remained as the only peaceful solution. Several countries welcomed this solution and the U.S. Department of State did not rule it out.

Coup allegations would eventually crumble with the completion of those elections, scheduled before the deposition of Manuel Zelaya and kept on schedule by the government of Roberto Micheletti. That would consummate the defeat of Chavez’s political strategy in Honduras.

It was then that Brazilian diplomacy began to take the lead and openly defend the interests of the Bolivarian bloc by frustrating any solution that did not meet the interests of Chavez.

IV – A Radical Maneuver: Zelaya’s Clandestine Return

Social and political peace reigned in Honduras. Thus, it was urgent to disturb the political arena and prevent the elections from taking place.

A radical maneuver was needed to rekindle the crisis. Nothing could be more useful than Zelaya’s clandestine return to the country.

Everything indicates that Hugo Chavez actively participated in the logistics of Mr. Zelaya’s return to the country. Chavez himself admitted that he knew about everything and disclosed that it was “a covert operation.”

Chavez’s confession only reinforces the certainty that Zelaya is a political puppet serving the interests of the Venezuelan caudillo.

From the moment that Manuel Zelaya took “refuge” in the Brazilian embassy in Tegucigalpa, Brazil visibly began to participate in the Chavista enterprise.

It becomes increasingly difficult to believe that Zelaya’s showing up at the door of the Brazilian embassy was the result of chance, since his stay there and the active collaboration of the Brazilian government have served its interests. Note also the coincidence with the speech by President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva at the U.N. General Assembly, during which he demanded an immediate return of Manuel Zelaya to office and condemned “coups d’état” such as the one in Honduras, while at the same time defending the Castro regime.

In a radio interview with a Honduran station, Zelaya said his plan to return to Honduras was prepared in consultation with Lula and [Brazilian Minister of Foreign Affairs] Celso Amorim. But even if he were lying, the confidence shown by Hugo Chavez in regard to Brazil is indicative of how the Venezuelan leader counts on Brazilian diplomacy to carry out his adventures and how the latter is complicit with his geo-political interests. It is understandable therefore that Manuel Zelaya has reaffirmed how essential Brazilian support is and reiterated his thanks to President Lula.

The fact is that Brazilian diplomacy, rather than demanding that Manuel Zelaya use discretion and refrain from any political demonstration, has allowed him to turn the Brazilian embassy into his own headquarters where he began to call for an uprising in Honduras and the overthrow of Micheletti. The possibility was even mentioned that Zelaya might install a parallel government there. The gravity of the situation is accentuated when one considers that several dozen Zelaya followers settled in the embassy with him, many of them with cloths hiding their faces while guarding the entrance to the building; it is not even certain that all of them are Hondurans.

Soon after Zelaya’s first harangues to his followers from the balcony of the embassy and in interviews given in the building, Zelaya supporters looted shops, destroyed property, burned tires and blocked roads; two lives were lost as a result of these disorders.

It is easy to understand why, in a statement released by the Foreign Ministry of Honduras, the government of President Lula was accused of meddling in that country’s internal affairs, and why Honduran Foreign Minister Carlos Lopez Contreras declared in an interview that “the government of President Lula has a serious international responsibility not only with the government of Honduras but also with the public and the stores looted by mobs instigated from within the mission of Brazil in Tegucigalpa” (“Chanceler de regime de facto acusa Brasil,” O Estado de S. Paulo, 9/26/2009).

In fact, Brazil, in an assault on the sovereignty of Honduras, has explicitly intervened in the country’s internal affairs in violation of international law, as noted by several experts. That attitude was reinforced by statements from President Lula that Zelaya has no deadline to leave the embassy and that “Brazil has nothing to talk about with these gentlemen who have usurped power.”

The desire to frustrate any negotiated settlement that fails to meet the interests of Hugo Chavez, has surfaced in the emergency meeting of the OAS, in which Brazil has aligned itself with Venezuela, rejecting the proposals of American diplomats.

The situation remains serious. In fact, those who planned for Zelaya’s return were counting on tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of his followers taking to the streets to support him, as Madrid’s newspaper, ABC, noted. But once again, it clearly turned out that the left failed to muster popular support.

All that was left for Zelaya, always from within the Brazilian Embassy, was to call for a final offensive by social movements and to preach acts of civil disobedience, as he did. This at the very moment that a member who chairs the Commission on Security and Drug Trafficking denounced to the Congress of Honduras, based on intelligence reports by the military and police in Central American countries, a massive campaign to smuggle weapons from El Salvador into Honduras to carry out terrorist acts in the country (“Denuncian masivo tráfico de armas hacia Honduras,” El Heraldo, 9/29/2009).

Is Chavez — with the possible assistance of Cuba, Nicaragua and other allies – preparing a bloodbath for Honduras? And in that case, will Brazil’s misguided diplomacy be ready to go ahead with this enterprise that can degenerate into violence and meet a tragic end?

Understandably, the U.S. ambassador to the OAS, Lewis Amsel, has described Zelaya’s clandestine return as “irresponsible” in addition to not serving “the interests of his people and of those who support a peaceful solution to the restoration of democratic order.”

The whole situation created with the “protection” given to former President Manuel Zelaya at the Brazilian embassy is telltale of the fact that the diplomacy of the Lula government has decided to cross a very dangerous threshold and assume the leadership of the geopolitical and ideological strategy of the so-called Bolivarian axis. As Veja magazine aptly put it in an editorial, “supporting Zelaya does not mean defending democracy; it means supporting the Chavez dictatorship” (9/30/2009).

V – Two Crumbling Myths

In the firmament of Latin-American diplomacy, two maxims emerged and became accepted almost as self-evident.

The first presented Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez as a histrionic, eccentric leader leading a revolution confused in its concepts and innocuous in practice. According to this version, the wild and crazy threats of Chavez were nothing but empty rhetoric.

The second maxim presented President Lula as a counterweight to Chavez’s radicality, prepared to contain his outbursts, as Lula is supposedly a moderate and pragmatic leftist leader and a reliable actor and necessary player in the resolution of local disputes.

So the left in Latin America is supposedly divided into two blocks, one of the radical left (led by Hugo Chavez) and a moderately leftist block (led by Lula).

The truth is that both maxims contributed to demobilize and weaken any resistance to the advancement of the left in Latin America.

Meanwhile, the two leaders were making substantial progress in their strategies, which were nothing but two sides of the same coin.

Anyone who focused more acutely on the diplomatic reality of the region would have realized that when Chavez’s disapproval rate rose or when he launched the boldest moves of his so-called Bolivarianism, President Lula and his diplomacy have consistently flocked to aid Chavez or members of his bloc.

Yet, mysteriously, many media and political analysts continued to repeat the two maxims, almost like a mantra.

Over the years, events have proved those versions wrong and, indeed, the two myths have now crumbled.

In fact, Lula never seriously tempered Chavez’s attitudes. And the proof is that the Venezuelan caudillo managed to pursue his radical program in Venezuela, where he openly implants a dictatorial socialist regime (which Lula has classified as an “excess of democracy”) extending his influence or interference to several countries; openly giving cover to the FARC terrorist guerillas and making alliances, including military ones, with Russia, China, Libya, Algeria and Iran – a clearly anti-American axis.

In a recent analysis, the respected magazine The Economist warned that there is a method to Chavez’s madness: “His avowed calculation is that by helping to stir up trouble for America in many places simultaneously, he can bring about the collapse of ‘the empire.’ The regimes he is so assiduously cultivating are, by this account, the nucleus of a new world order.” And the magazine warns that the world should start to take his designs more seriously (“Friends in low places,” 9/15/2009).

President Manuel Zelaya’s clandestine return to Honduras and his reception at the Brazilian embassy fit right into the context pointed out by The Economist.

In an outburst, the Lula-Worker’s Party diplomacy revealed its true face, showing it is willing to play rough and to actively support Chavez and his “twenty-first century socialism,” working to destabilize Latin America and increasingly undermine the influence of the United States in the region.

Conclusion

The Honduran crisis is highly revealing and is a serious warning sign. The government of President Lula, despite certain appearances, is not interested in solving it in accordance with Honduran institutions. Instead, they are willing to force the small Central American nation to surrender to Chavismo.

Zelaya and Lula

In its subservience to the designs of a left-wing ideology, Brazil’s diplomacy does not reflect the beating heart of Brazil as a whole, as public policies have long failed to take into account the conservative and Christian fibers of the nation’s people – one of the most prestigious and compelling components of the nation’s mentality.

The aggressiveness and radicalization that increasingly mark our diplomatic policies, in addition to possibly dragging Brazil to an undesirable position of belligerence, are averse to the mentality of average Brazilians.

What will our compatriots think when they see themselves involved in conflicts they never sought, only because the ideological fanaticism of some has led them to misadventures such as the present one?

What uneasiness, disconcertedness and hallucinatory sense of being sidetracked from the nation’s historic mission will Brazilians feel when they see the tactical capabilities of the country’s geographic configuration, the immense riches of her subsoil, her booming agriculture and dynamic industry being employed to spread an ideology alien to their longings and contrary to their Christian principles?

It is urgent for Manuel Zelaya to leave the Brazilian legation and stop using it as a headquarters from which he issues calls for a revolt that could lead to a fratricidal struggle among Hondurans. If our government continues to sponsor the Chavista adventure of Manuel Zelaya, it will be responsible for it to a large degree.

Honduras needs peace and respect for its sovereignty and not war cries coming from the Brazilian embassy in Tegucigalpa.

More important than anything else, little Honduras, Brazil and all Latin America must be safe from the intrigues, threats, incursions, and a possible future dominance of “twenty-first century socialism.”

In our view, we need to form a broad front in Brazil – not so much based on party affiliation but on her real interests – which effectively opposes the excesses of a diplomatic policy that has long ignored our legitimate national interests replacing them with an imperialist ideology; an ideology that is trying to revive in our usually peaceful continent a wake of humiliation, confrontation, misery and pain that Marxist ideas have imposed on Russia, the countries of Eastern Europe, China, North Korea and Cuba, to mention just a few.

We close this statement by lifting our prayers to Our Lady Aparecida, Queen of Brazil, begging her not to allow alien ideologies to disturb peace in Latin America, turning Brazil into a focus of insecurity and disintegration.

São Paulo, October 3, 2009

Associação dos Fundadores

Adolpho Lindenberg

Caio Xavier da Silveira

Celso da Costa Carvalho Vidigal

Eduardo de Barros Brotero

Paulo Corrêa de Brito Filho

Plinio Vidigal Xavier da Silveira