Many Catholics today are unaware of the immense contributions of the Ultramontanes of the nineteenth century to the resurgence of Catholicism worldwide. Prof. Fernando Furquim de Almeida (1913-1981) studied the Movement and produced dozens of articles detailing its work. We have edited these articles and will be featuring them. They highlight the actions of Ultramontane leaders in England, Spain, Italy, France and Ireland.

In 1832, Pope Gregory XVI condemned French Priest Félicité Robert de la Mennais’s liberal errors in the Encyclical Mirari Vos. Since this action preceded the emergence of the English Catholic movement, it made it easy for Nicholas Cardinal Wiseman, Archbishop of Westminster and a decided ultramontane, to prevent some of the more extreme liberal errors from contaminating that Movement.

Unfortunately, the same did not stop the French deviation of so-called Catholic liberalism. The bishop of Orleans, Most Rev. Felix Dupanloup, gathered the remnants of France’s liberal Catholic wing around him. He especially promoted the systematic and relentless employment of the famous distinction between thesis and hypothesis.

Of course, Catholic liberalism did not appear in all countries with the same characteristics. The target environment shaped its errors, often producing movements fighting each other over details but allied in the fight against Ultramontanism.

The intense social life of the nineteenth-century English upper classes resulted from their educations at Oxford and Cambridge. Their alumni spread the dominant mentality of these universities throughout the country. From the humblest worker to the Royal Family, almost no one remained uninfluenced by their elegantly humanist teachings, filled with patristic quotations with an Anglican interpretation.

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

For their part, the Irish were the great strength of English Catholicism, as their homeland’s periodic famines forced them to emigrate. Since they were not under the influence of large universities, the English saw them as ignorant. The English prejudice that the intellectual level of the Catholic clergy and laity was shallow was widespread. Catholic liberals took advantage of those sentiments to penetrate England, applying the methods used by English university students to Catholic intellectuals.

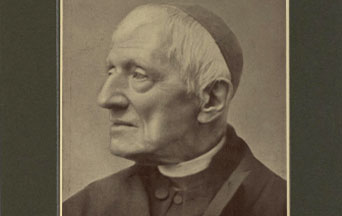

Oxford Movement converts were usually Ultramontanes and rallied around Cardinal Wiseman. Unfortunately, the same was not true of the Movement’s one-time leader, Fr. John Henry Newman. Imbued with the spirit acquired in his youth, he fluctuated between orthodoxy and liberalism. A lack of definition marred all his works.

Fr. Newman’s preconceived ideas about the cultural level of Catholics caused countless frictions with both Cardinal Wiseman and his own companions. Fathers Frederick Faber and John Dalgairns, Newman’s friends and collaborators in founding the Birmingham Oratory, were forced to separate from him. They opened a new Oratory in London that soon became a stronghold of Ultramontane Catholicism.

In 1848, a group of liberal Catholics led by Richard Simpson took Fr. Newman’s prejudices to an extreme. Its mouthpiece, The Rambler magazine, had the specific purpose of disseminating historical studies. Yet its first issue already showed the influence of Ignaz von Doellinger, the famous leader of Catholic liberalism in Munich.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Von Doellinger sought to rewrite Church history using only investigative methods proper to historical science. This approach completely ignored the supernatural element. The new magazine proclaimed its plan to do the same. The dangers of this scientific exclusivism became apparent later. It led to the creation of historical theology, whose teachings tenaciously opposed the Thomism being reborn in Italy. These attitudes led several German bishops to combat papal infallibility at the First Vatican Council and earned von Doellinger the sad celebrity of apostasy.

However, at the time of its founding, many found the journal’s intellectual attitude reasonable. The Rambler was welcomed even by Cardinal Wiseman, unafraid of serious and conscientious scientific investigation.

In 1856, The Rambler acquired a brilliant collaborator with the return to England of Lord John Acton, who had finished his studies in Germany with Doellinger. He was the son of an Englishman and a German noblewoman, the grandson of a minister of the King of Naples and a nephew of Cardinal Acton. After his father’s death, his mother married Lord Granville, an English politician. Granville greatly influenced Acton.

This young aristocrat put all the prestige of his social situation at the service of Catholic liberalism. His life’s ideal was to write a history of freedom. He proclaimed himself a “man who renounced everything in Catholicism incompatible with liberty and everything in politics incompatible with the Catholic faith.” Extremely intelligent and highly connected across Europe, his membership gave The Rambler a new impetus.

In 1859, Lord Acton became director of the journal, which quit historical studies and became the mouthpiece of Catholic liberalism in England. Other than von Doellinger, its writers included Bishop Dupanloup, the Comte de Montalembert, Father Auguste Gratry, and other European liberal Catholic leaders.

Science Confirms: Angels Took the House of Our Lady of Nazareth to Loreto

The old Catholic group that had opposed Cardinal Wiseman’s reestablishment of the Church from the beginning was a natural ally of The Rambler. Always fearful of confronting Protestantism, its members could only welcome this attempt to mold Church doctrine to their ideals.

Disorganized and incapable of enthusiasm, the English liberals would not have been formidable except for the support they received from Most Rev. George Errington, coadjutor Bishop of Westminster. Concerned about his own struggles for the conversion of England, Cardinal Wiseman entrusted the administrative part of the diocesan government to Bishop Errington, an accomplished administrator.

The rise of Catholic liberalism completely altered their relationship. Driven by his natural conformism and the necessity to constantly intervene to reconcile differences between the faithful of the archdiocese, the coadjutor bishop often took positions contrary to the Cardinal’s. These actions seriously harmed the latter’s apostolate and served as a shield for liberal Catholics. Bishop Errington destroyed the good harmony that had hitherto existed in the government of the archbishopric.

Between Newman’s indecision and Lord Acton’s boldness, every position was represented. However, Bishop Errington and The Rambler were key. By 1860, England seemed to follow in the footsteps of other European countries, where liberalism again claimed leadership in the Church and tenaciously opposed the progress of orthodoxy.