Many Catholics today are unaware of the immense contributions of the Ultramontanes of the nineteenth century to the resurgence of Catholicism worldwide. Prof. Fernando Furquim de Almeida (1913-1981) studied the movement and produced dozens of articles detailing the movement’s work. We have edited these articles and will be featuring them. They highlight the actions of Ultramontane leaders in England, Spain, Italy, France and Ireland.

The help of the Oblates of Saint Charles, which Father Henry Manning founded in 1856, enabled him to broaden the scope of his apostolate.

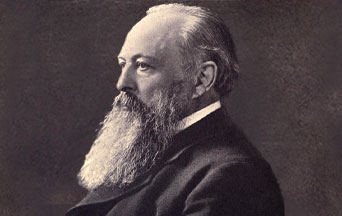

One of Father Manning’s great concerns was the increasingly liberal publication, The Rambler. He feared that Lord John Acton’s magazine would win the trust of the unsuspecting faithful and turn the English Catholic movement away from orthodoxy. To oppose it, he planned to use the Dublin Review, founded by Nicholas Cardinal Wiseman and Daniel O’Connell. The Review, he hoped, would facilitate the great return to the Church that the Oxford Movement was leading.

The Dublin Review was created to clarify the doubts of Protestants in good faith. It was not, however, prepared to combat deviations within the Church. A complete overhaul was needed. The magazine was entirely refashioned. Father Manning decided it would be written by Oxford converts who remained faithful to orthodoxy. The new writers’ team was led by the mathematician and theologian William Ward, who lived up to the trust placed in him. In a short time, he transformed the Dublin Review into a combative and genuine English counterpart of Louis Veuillot’s famous l’Univers.

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

The English episcopate viewed The Rambler’s bold articles with apprehension. They supported Father Manning’s reforms at the Dublin Review. However, Father Manning believed he could change Acton’s publication by appealing to the goodwill and obedience of its editors before taking drastic measures. Father Newman seemed the right man to mediate an accommodation. Although Father Newman criticized the Rambler writers’ aggressively independent tone vis-a-vis ecclesiastical authority, as well as its editors’ dry and sterile intellectualism, he maintained good relations with them. He assiduously corresponded with John Moore Capes, the magazine’s director until 1858, and his successor, Richard Simpson.

A meeting between Father Newman and John Acton was arranged in London. The Oratorian asked that The Rambler work gradually to raise the intellectual level of Catholics and avoid purely theological questions. Acton had with him an article by Ignaz von Doellinger that had been reported to the Holy Office. Acton indignantly protested against those who had denounced it just because Doellinger maintained that there was a close link between Jansenist ideas and those of Saint Augustine. The obstinacy of The Rambler’s writers and the attitude with which they received Newman’s intercession were consistent with that spirit of rebellion. Commenting on the interview, Acton wrote Simpson that he would like to see Newman’s reaction “to this news, groaning at length and rocking back and forth in front of a fireplace, like an old woman with a toothache.”

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Naturally, faced with this mindset, Father Newman’s good offices would not succeed. As the magazine failed to change its conduct, the episcopate decided to intervene more energetically. On June 16, 1859, the Most Rev. William Ullathorne, Bishop of Birmingham, whose influence in church circles was second only to Cardinal Wiseman’s, wrote Newman. Bishop Ullathorne informed him that Simpson must resign as The Rambler’s director. He urged the Oratorian to take suitable measures to resolve the matter once and for all. Not without difficulty, Father Newman got Simpson to obey. Publisher James Burns, Acton, Doellinger, and Simpson insisted that Newman assume the director’s position.

Agreeing after long hesitation, Father Newman did not impose on The Rambler the necessary modifications to put it on the right path. Thirty years later, he tried to justify himself by saying he planned to gradually change the paper’s orientation, especially its editors’ way of being. At the same time, he did not wish to sacrifice the reputation of men he believed to be, deep down, sincere Catholics. He thought it would be “disloyal, selfish, objectionable, and cowardly to make acts of confession and repentance on his own and to proclaim a change of direction.”

The first issue published under the new direction did not satisfy the episcopate. After a long conversation in which he failed to convince Newman of his error, Archbishop Ullathorne demanded that he resign but gave him time to do so. In the July issue, which would be the last under his administration, the future cardinal published an article titled “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine.”1 Alarmed by certain statements in this work, Bishop Thomas Brown, O.S.B. of Newport, denounced it to the Holy Office. This action helped considerably to shake the remnants of confidence that English Catholics still placed in the celebrated Oratorian.

Science Confirms: Angels Took the House of Our Lady of Nazareth to Loreto

English Catholics, including many Oxford converts, had already turned against Newman. Indeed, the Catholic University of Dublin failed because he tried to ally himself with Young Ireland, which had seriously damaged O’Connell’s apostolate. Further, Newman had broken with Father Frederick Faber and shown undisguised ill-will toward Cardinal Wiseman’s work. His influence had diminished, and his present hesitation helped to nullify it altogether. Without clearly allying himself with the liberals, it was evident that Newman sympathized with them.

Thus, obeying an order of the Bishop of Birmingham, Father Newman did not wholly abandon the magazine. One day, proofreading a study on Saint John Chrysostom, he saw a violent article by Simpson against the Encyclical Mirari vos, which had condemned Lamennais and L’Avenir in 1832. Indignant, Newman demanded that the article not be published. The editors refused his request, and he withdrew definitively. Despite everything, he did it discreetly not to harm the magazine. Subsequently, the public assumed it continued under his guidance.

Freed from this moderating influence, the writers laid bare their liberal convictions. That forced Newman to send the Tablet a reluctant note communicating he had severed all connection with The Rambler. Offended, John Acton broke definitively with Father Newman, who thus ended his collaboration with the mouthpiece of liberal Catholics.