The following article is adapted from the book Liberation Theology: How Marxism Infiltrated the Catholic Church written by Julio Loredo de Izcue.

✧ † ✧

Interpreting the pastoral line of Leo XIII in their own way, Americanists saw it as an incentive to continue on the path of Liberalism. “The title which above all others he has merited and which history will award is this—the pontiff of his age,” Archbishop John Ireland commented. “The reconciliation of the Church with modern times is Leo’s work.”1

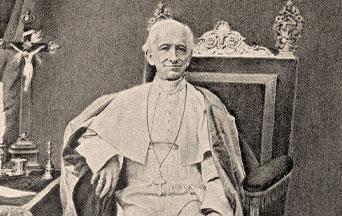

To dispel all doubt, in 1895 Pope Leo XIII wrote to American bishops the apostolic letter Longinqua oceani, in which, after expressing his joy at the growth of the Church in America, he expressed some concerns and advised pastors to be particularly vigilant.

The translation into French and subsequent dissemination in Europe of the life of Fr. Issac Thomas Hecker (1819—1888), founder of the Paulist Fathers and a leading figure in the Americanist movement, revered by European liberal Catholics almost as a patron saint, led the Roman pontiff to act more resolutely. On January 22, 1899, he wrote the letter Testem benevolentiae, addressed to James Cardinal Gibbons, archbishop of Baltimore, and delivered to all the bishops of the United States.

Leo XIII condemns the view that “the Church should shape her teachings more in accord with the spirit of the age and relax some of her ancient severity and make some concessions to new opinions.” He went on to condemn the “opinion of the lovers of novelty, according to which they hold such liberty should be allowed in the Church, that her supervision and watchfulness being in some sense lessened, allowance be granted the faithful, each one to follow out more freely the leading of his own mind and the trend of his own proper activity.” The Church, the pope states, cannot hide any aspect of her doctrine or discipline on the pretext of appearing more acceptable to modern man lest she risk losing her identity.

Touching a key part of the Americanist spirit, Leo XIII censures the prevalence of active virtues over supernatural or passive ones, and concludes, “We are not able to give approval to those views which, in their collective sense, are called by some ‘Americanism.’”2

In Europe, the letter Testem benevolentiae was correctly interpreted as a condemnation of liberal Catholicism. Many bishops reproduced it in their diocesan publications. Almost all Americanist leaders wrote submissive letters to Leo XIII, beginning with Archbishop Ireland, whose letter was published in French in L’Osservatore Romano of February 24, 1899. In it the archbishop of Saint Paul speaks of mere “misunderstandings” and rebuffs the charge of “Americanism,” calling it a “danger which was not understood by all the people of the United States” and which, according to him, is only attributable to the “astonishing confusion of ideas” created by “enemies of the Church in America.” The prelate closes the letter protesting against his accusers: “We cannot but be indignant that such an injury has been done to us—to our bishops, to our faithful people, to our nation, in designating by the word ‘Americanism’ . . . such errors and extravagances as these.”3

The overly kind reception of such letters by Vatican authorities together with the lack of any disciplinary measures, conveyed the impression that the Americanist crisis had been overcome. That impression was further reinforced in a series of articles by democratic priest Fr. Pierre Dabry who, as Albert Houtin put it, “seems to have revived the courage of democratic Catholics.”4

Americanism and Modernism

Americanism in the late nineteenth century served as a rallying banner for left-leaning people who, some years later, would show sympathy for modernist errors. Archbishop John Ireland’s views, for example, were so dangerously close to those of Modernism that he fully expected to be condemned by St. Pius X during the modernist controversy of 1905—1914. Most Rev. John Lancaster Spalding (1840—1916), bishop of Peoria and founder of the Catholic University of America, also tended to modernist doctrines. “While Spalding stopped short of the modernists’ attempts to reformulate dogma,” historian Robert Cross comments, “he shared their desire to destroy the sharp separation between secular and spiritual.”5

In its theological implications, Americanism foreshadowed Modernism. If the Americanists’ support for Modernism was not more vocal, it was due essentially to the cautiousness imposed on them by the letter Testem benevolentiae. In his 1907 encyclical Pascendi Dominici gregis condemning Modernism, St. Pius X pointed to an element common to the latter and Americanism: “With regard to morals, [the modernists] adopt the principle of the Americanists that the active virtues are more important than the passive.”6

Describing the modernist controversy, Msgr. John Tracy Ellis, a historian of American Catholicism, quotes Daniel Rops of the Académie Française who affirms that “the Americanism of Archbishop Ireland and Fr. Hecker constitute[d] a practical prelude to Modernism.”7 For his part, Italian theologian Fr. Emanuele Chiettini also noted that Americanism contained in germ “many of the errors later condemned by Pius X under the generic name of Modernism.”8

Footnotes

- Ireland, Church and Modern Society, 1:408, 423.

- Leo XIII, apostolic letter Testem benevolentiae (Jan. 22, 1899).

- John Ireland, Letter to Leo XIII (Feb. 22, 1899). We quote from a contemporaneous English translation. “Ireland to the Pope,” The New York Times, Mar. 22, 1899.

- M. Dabry, in Vie catholique, Mar. 14, 1899, quoted in Albert Houtin, L’américanisme (Paris: Librairie Émile Nourry, 1904), 369. An article published in L’Italie on March 6, 1899, sheds light on the story of the apostolic letter Testem benevolentiae by showing the extent to which liberal errors had penetrated high-ranking levels. The draft was written by Cardinals Satolli and Mazzella, both ultramontanes, and contained a clear condemnation of Americanism. Then, according to the French publication, fortunately, with his usual wit and secret sympathy for Americanism, the pope intervened. “Aided by Cardinal Rampolla, who also quietly favored the cause of Americanism, he introduced radical changes to the draft of Cardinals Satolli and Mazzella. They cut, expurgated, patched, changed it, and added pieces. The original document became absolutely unrecognizable.” (Houtin, L’américanisme, 370—71)

- Cross, The Emergence, 40.

- St. Pius X, encyclical Pascendi Dominici gregis (Sept. 8, 1907), no. 38.

- Daniel Rops, “Il y a cinquante ans, le modernisme,” Ecclesia Lectures Chrétiennes, no. 77 (Aug. 1955), 13. See Msgr. John Tracy Ellis, “Les États-Unis depuis 1850,” in Nouvelle histoire de l’église (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1975), 718.

- Emanuele Chiettini, s.v. “Americanismo,” Enciclopedia cattolica (E.C.) (Vatican: Ente per l’Enciclopedia Cattolica e per i Libro Cattolico, Soc. p. a., 1948), 1:1056. On the connection between Americanism and Modernism, see Margaret Mary Reher, “Americanism and Modernism: Continuity or Discontinuity?” U.S. Catholic Historian, no. 1 (1981): 87—103; R. Scott Appleby, “Modernism as the Final Phase of Americanism,” The Harvard Theological Review 81, no. 2 (Apr. 1988): 171—92.