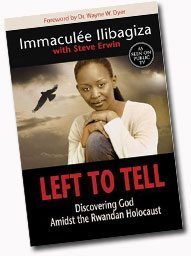

Left to Tell is the personal story of Immaculée Ilibagiza and her harrowing survival of the Rwandan Genocide of 1994.

Left to Tell is the personal story of Immaculée Ilibagiza and her harrowing survival of the Rwandan Genocide of 1994.

While many other books have dealt with the subject, this volume stands out, because in addition to the riveting account of horror and survival, there are many valuable lessons that can be drawn from the storyline.

Immaculée was born into a middle class home. Her parents were both highly respected Roman Catholic members of their community. They were educated Tutsis, and, as such, they got along with the Hutu members of their community.

In 1994, militant Hutu nationalist groups, impassioned by the death of Rwanda’s Hutu president, began attempts to exterminate the Tutsis. The infamous Rwandan Genocide of 1994 had begun. Over the next 100 days, some estimates claim over one million Tutsis were killed.

When the genocide ended, almost all of the Tutsis in Immaculée’s community had been slaughtered. She only survived by hiding in a tiny bathroom with seven other women for ninety-one days. To avoid discovery, they could only move twice a day and never spoke.

Left to Tell is intensely captivating. Besides being inspiring and terrifying, it is also highly educational and full of lessons to be learned.

First, it shows that that in a society which lacks respect for God’s laws, the barrier between apparent tranquility and violence is paper-thin. Before the killing began, Hutus and Tutsis worked, married, went to school, played and even prayed together. Once the violence erupted, these friendly relations were immediately exchanged for violence and bloodshed.

A second lesson is the danger of false optimism. How many times in history have the good suffered the effects of a danger they could have defeated, but refused to face?

When the Rwandan genocide began, Immaculée’s brother advised the family to leave the country. Blinded by false optimism, they refused. By the time they perceived the extent of the catastrophe, it was too late.

A third lesson is the value of confident prayer. Immaculée prayed fervently during her ninety-one days in hiding. During that time, there were thorough searches of the house on a daily basis. To make matters worse, the Protestant minister who had hidden the eight women threatened many times to turn them in since his entire family, who did not know of the women’s presence, were radical Hutus.

During the searches, machete-wielding killers suspected Immaculée’s presence. Many times they even called out her name, but never found her.

Despite the likelihood of her capture, Immaculée prayed with tremendous confidence. This confidence in Our Lord and Our Lady was most inspiring because, humanly speaking, her situation was hopeless.

Immaculée finishes the book, forgiving the murderous Hutus who slaughtered her countrymen. Thankfully, her forgiveness is not an apology for their actions, but a true Catholic forgiveness, in which she admonishes their crimes and declares that they must be held accountable for them. Nevertheless, she realizes that personal hatred is self-destructive.

Without giving it an unqualified seal of approval, the TFP heartily recommends this book, especially in the light of the lessons it teaches. The reader will certainly derive his own lessons from this worthwhile read.