(The following article appeared in the Brazilian Catholic newspaper, Legionário, on June 15th, 1947. The author speaks with amazing insight about the rise of Islam and makes observations that are very applicable to our days. We have translated and adapted the article for the benefit of our readers. The end of the article refers to what were then current events and which are no longer familiar to

(The following article appeared in the Brazilian Catholic newspaper, Legionário, on June 15th, 1947. The author speaks with amazing insight about the rise of Islam and makes observations that are very applicable to our days. We have translated and adapted the article for the benefit of our readers. The end of the article refers to what were then current events and which are no longer familiar to

most readers. These facts are included to give the context from which the author wrote.)

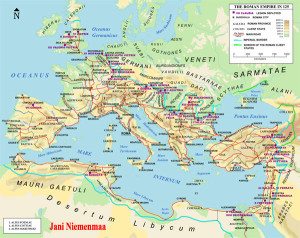

When we study the sad story of the fall of the Western Empire, it is hard for us to understand the Romans’ shortsightedness, tranquility and indifference toward the looming danger. To further aggravate matters, Rome suffered from an inveterate habit of winning. At its feet were the most glorious nations of antiquity: Egypt, Greece, and all of Asia. The ferocity of the Celts had been definitely softened. The Rhine and the Danube constituted a splendid natural defense to the Empire. How could anyone fear that the barbarians, who roamed the virgin forests of central Europe, could pose a serious risk to such an immense political edifice?

Accustomed to this view, the Romans lacked the flexibility to understand the new situation gradually being created. As the barbarians crossed the Rhine and began their raids, they only met weak, indecisive and inadequate resistance from the Roman legions. But the Romans continued to ignore the danger, obsessed on the one hand with an all-absorbing thirst for pleasures, and on the other, misled by what the detestable Freudian terminology would call a “superiority complex.” This explains the deadly tranquility which they kept to the end.

Yet even taking into account the mystery of Roman inertia, the overall picture seems peculiar and perhaps a bit oversimplified. We will understand it in a much more lively fashion if we consider another great mystery that takes place before our eyes and in which we somehow participate: the great inertia of the Christian West facing the resurrection of African-Asian nations. The subject is much too vast to be treated entirely. To understand it well, it suffices to consider only one aspect of this phenomenon: the renewal of the Muslim world.

This is a topic that Legionario, already accustomed to being misunderstood, has approached with an insistence that sometimes seemed inopportune. But the question deserves to be examined once again at greater depth.

Let us quickly recall some general facts about the problem. As is known, the Muslim world spans a territory that begins in India, passes through Arabia and Asia Minor, Egypt, and ends on the Atlantic Ocean. Islam’s zone of influence is immense from all points of view: territory, population, and natural resources. However, until some time ago, certain factors rendered all this power almost completely useless. Obviously, the religion of the Prophet is the bond that unites Muslims from all over the world. But this religion presented itself divided, weak, and totally devoid of notable men in the sphere of thought, command or action.

Mohammedanism vegetated, a fact that seemed to perfectly suit the zeal of the high dignitaries of Islam. The same taste for stagnation and a merely vegetative life was an evil that also affected the economic and political life of the Muslim peoples of Asia and Africa. No man of value, no new ideas, no truly great enterprise could rise and prosper in this atmosphere. Each Mohammedan nation closed up on itself, indifferent to everything but the small and quiet delights of everyday life. So, each lived in its own world, differing from others by profoundly different historical traditions. They were all separated by mutual indifference, incapable of understanding, desiring or carrying out a common task. In this highly depressed religious and political framework, the development of the natural resources of the Muslim world—riches which taken together give the region some of the greatest potential in the world—was clearly impossible. Everything therefore was nothing but ruin, breakdown and torpor.

While the East so dragged along, the West attained the zenith of its prosperity. Since the Victorian era, an atmosphere of youth, enthusiasm and hope spread across Europe and America. The progress of science had renewed the material aspects of Western life. The promises of the Industrial Revolution were seen as creditworthy, and in the last years of the nineteenth century some people even saw the coming twentieth century as the golden age of mankind.

Of course, a Westerner placed in this environment was fully aware of the inertia and impotence of the East. He would see any talk about the possibility of a resurrection of the Mohammedan world as something as unworkable and outdated as a return to costumes, methods of warfare and political outlook of the Middle Ages.

Today, we are still living this illusion. And like the Romans who trusted the Mediterranean that separated them from the Islamic world, we fail to realize that new and extremely serious phenomena are taking place in the lands of the Koran.

vegetative life was an evil that also affected the economic and political life of the Muslim peoples of Asia and Africa.

It is difficult to cover such vast and rich phenomena in a short space. But in a very general way, one can say that, after the Great War (World War II), the whole East — understood in a very broad sense as covering all areas of non-Christian civilization in Asia and Africa — began to take a very pronounced anti-European attitude. This reaction concerned two somewhat contradictory movements, both very dangerous to the West.

On the one hand, the Eastern nations were bearing the Western military and economic yoke with growing impatience and manifesting an increasingly pronounced aspiration to full sovereignty, to develop independently their economic potential and to set up their own large armies. To be sure, this aspiration implied a certain “Westernization,” that is, that they import Euro-American military, industrial and modern agricultural techniques as well as financial and banking systems. On the other hand, however, this patriotic surge caused a renewed enthusiasm for national traditions, national customs, national worship, and national history. It is superfluous to add that the degrading spectacle of corruption and divisions to which the Western world was exposed contributed to encourage hatred of the West. Hence the rise throughout the East of a new interest for the old idols and for a “neo-paganism” a thousand times more combative, feisty and dynamic than the old. Japan is quite a typical, perhaps ultra-typical example of the whole process we are trying to describe. The ideological and political group that lifted her to the rank of major power and aspired to Japanese world domination was precisely one of those neo-pagan groups stubbornly attached to old concepts of the Emperor’s divinity.

In addition, a slower but no less vigorous phenomenon than the one in Japan occurred throughout the Eastern world. Because of this, India is on the verge of gaining its independence; today Egypt and Persia enjoy a privileged situation on the international scene and progress at a rapid pace. Well before this, Mustafa Kemal had renewed Turkey. All these nations, we can say these “powers,” are proud of their past, traditions and culture, and are keen to keep them; and at the same time they are proud of their natural resources, political and military possibilities, and growing financial progress. They grow richer by the day, build cities endowed with effective government mechanisms, a well-trained police, strictly pagan but well-developed universities, schools, hospitals, museums, and, in short, everything that somehow means power and material progress to us. In their coffers, gold accumulates. Gold means the ability to buy weapons. And weapons mean global prestige.

It is interesting to note that the Nazi example strongly impressed the East. If a large country like Germany has a government that abandons Christianity and does not blush to return to the old idols, how is it shameful for the Chinese or Arabs to do the same by remaining in their traditional religions?

All this transformed the Islamic world and produced in all Mohammedan peoples, from India to Morocco, a shudder that means that the millennial slumber is over. Pakistan — a Muslim Hindu state on the brink of independence — Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Egypt are the high points of the movement of Islamic resurrection. But in Algeria, Morocco, Tripolitania, Tunisia, unrest also grows intense. The vital nerve of Islam revives in all these peoples, rekindling in them a sense of unity, a notion of common interests, concerns of solidarity, and a taste for victory.

None of that stayed in the realm of possibility. Today the Arab League, a vast confederation of Muslim peoples, unites the entire Muslim world. It is the contrary of what Christendom used to be in the Middle Ages. The Arab League acts as a large block facing non-Arab nations and fosters insurrection throughout North Africa. The flight of the grand mufti was a clear manifestation of the League’s strength. Even more than this, the release of Abd-el-Krim is an affirmation of the League’s deliberate purpose to intervene in the affairs of Northern Africa by promoting the independence of Algeria, Tunisia, Tripolitania, and Morocco.

Does it take much talent, insight, and exceptional information to realize what this danger means?

The preceding article was originally published in O Legionario, No. 775, on June 15, 1947. It has been translated and adapted for publication without the author’s revision. –Ed.