""""[vc_column_text] The questions about the Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitiae presented to Pope Francis by four cardinals in the form of Dubia (Doubts) remain without an official answer. Rather than clarifying the document, the indirect answers given by churchmen close to the Pontiff have only reinforced the questions raised by the four zealous cardinals, American Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke, Germans Walter Cardinal Brandmüller and Joachim Cardinal Meisner, and Italian Carlo Cardinal Caffarra).1

The questions about the Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitiae presented to Pope Francis by four cardinals in the form of Dubia (Doubts) remain without an official answer. Rather than clarifying the document, the indirect answers given by churchmen close to the Pontiff have only reinforced the questions raised by the four zealous cardinals, American Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke, Germans Walter Cardinal Brandmüller and Joachim Cardinal Meisner, and Italian Carlo Cardinal Caffarra).1

The most recent “indirect answer” comes by way of Francesco Cardinal Coccopalmerio, president of the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts, “one of the closest and most listened-to aides” to Pope Francis.2

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Did Pope Francis Not Respond to the Dubia?

One cannot say that Pope Francis did not actually answer the cardinals’ Dubia, at least indirectly. His actions, gestures, attitudes and omissions reveal his thought as much as explicit words.3 And the support he has given to bishops’ conferences that interpret Amoris Laetitia as a permission, at least in principle, for divorced and civilly “remarried” Catholics to receive sacramental absolution and Communion makes clear his own interpretation of Chapter 8 of Amoris Laetitia.4

Fr. Thomas Reese, S.J., former editor in chief of Jesuit America Magazine, wrote on March 9, 2017, the following in the liberal National Catholic Reporter:

“Cardinal Burke and the pope’s critics are right; the pope is presenting a new way of thinking about moral issues in Chapter 8 of Amoris Laetitia. He is moving the church away from an ethics based on rules to one based on discernment. Facts, circumstances, and motivations matter in such an ethics. Under this approach to moral theology, it is possible to see holiness and grace in the lives of imperfect people, even those in irregular marriages.”

Cardinal Coccopalmerio, an Authoritative Spokesman for Pope Francis

Back to Francesco Cardinal Coccopalmerio.

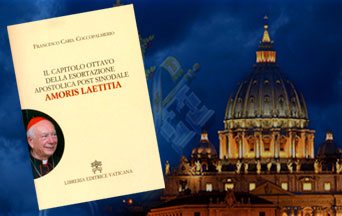

This past February, “at the request of the Pontiff himself” (“su richiesta dello stesso Pontefice”5), he published a thirty-page booklet titled, “Il Capitolo Ottavo della Esortazione Apostolica post Sinodale Amoris Laetitia” (“Chapter 8 of the post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitia”) printed by Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

Strangely enough, Francesco Cardinal Coccopalmerio never came to the book launching of his book or to the press conference that was supposed to take place at the event.

Yet, on February 21, a few days later, he granted an interview to Edward Pentin,6 the Rome correspondent of the National Catholic Register. In that interview the cardinal summarizes the argumentation contained in his booklet.

Asked whether the Pope had reviewed his book on Amoris Laetitia before its publication, Cardinal Coccopalmerio answered negatively but added, “I spoke with the Pope at other times about these questions, and we always thought the same; also during the synods.”

Thus, this interview carries not only the weight of the cardinal’s present office but also of his affirmation that he and the Pope think likewise about the moral problems dealt with in Amoris Laetitia—the object of his book and the interview, as well as of the Dubia presented by the four cardinals.

Let us review a few statements by the president of the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts in that interview. To begin with, one must say that in addition to the vicissitudes common to any interview, the cardinal’s words are slippery, confusing, contradictory and fraught with ambiguity (for the correct doctrine see Box “A Previously Condemned Doctrine” on Veritatis Splendor).[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]""[vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Saint Paul Forbids the Practice of Evil to Draw any Good

The cardinal says that a person often knows that he finds himself in an erroneous situation but is unable to get out of it, “[b]ecause if they did, if they were to leave these unions, innocent people would be hurt.”

He hypothesizes about the case of a woman living with a man who was abandoned by his legitimate wife, and with whom she had three children.7 That woman knows that she is in the wrong and would like to get out of that situation but is unable to do so as that would harm her children and companion. According to the cardinal, she would say, “‘I am leaving this mistaken union because I want to correct my life, but if I did this, I would harm the children and the partner’; then she might say: ‘I would like to, but I cannot’.”

The actions of the woman in this hypothetical example of the cardinal would clearly oppose the teaching of Saint Paul that one may not do an evil in order to draw a good from it.8 For she would remain in a situation of sin, concur with the sin of her companion, as well as give scandal to the children.

In his example (which illustrates his doctrine) the cardinal does not distinguish between a relative good of the natural order—her affection for her companion and children—and the supernatural good—recovering sanctifying grace and practicing true love: charity, which consists in loving one’s neighbor for the love of God. And therefore, by following God’s Law.

Morals Cannot Be Separated From the Spiritual Life

In the moral conception of the illustrious prelate, one does not see a search for “that wisdom which teaches us to lay up treasures in Heaven by exchanging the goods of this world for those of eternity.”9

Although his hypothetical woman makes clear that she will not abandon sin, the cardinal deems her sheer intention (albeit ineffective) sufficient to give her the Sacraments.

“In precisely these cases” the cardinal says, “based on one’s intention to change and the impossibility of changing, I can give that person the sacraments, in the expectation that the situation is definitively clarified.”

Journalist Edward Pentin insists with the cardinal: how can this situation “in which you say it is better for a woman to continue in her sinful situation” be reconciled with the teaching of Saint Paul and the Church Magisterium that “it is never permissible to deliberately do evil for the sake of a greater good.”

The cardinal answers:

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_message message_box_color=”grey” icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-angle-right”]

A Previously Condemned Doctrine

In his interview Cardinal Coccopalmerio attributes the morality of a human act to the intention of its agent and not to its nature or object of the act itself. Thus, even if a person practices a bad act violating some Commandment of the Law of God, the act will be good if the intention is good.

This theory was condemned as being contrary to Catholic doctrine as recently as John Paul II’s Encyclical Veritatis Splendor, based on Saint Thomas Aquinas and on the Council of Trent:

“The morality of the human act depends primarily and fundamentally on the ‘object’ rationally chosen by the deliberate will, as is borne out by the insightful analysis, still valid today, made by Saint Thomas” (No. 78).10

“… [C]ertain moral theologians have introduced a sharp distinction, contrary to Catholic doctrine,11 between an ethical order, which would be human in origin and of value for this world alone, and an order of salvation, for which only certain intentions and interior attitudes regarding God and neighbor would be significant. This has then led to an actual denial that there exists, in Divine Revelation, a specific and determined moral content, universally valid and permanent.” (No. 37)

Declaration of Fidelity

Recalling the existence of intrinsic evil, Veritatis Splendor states:

“… Saint Thomas observes that ‘it often happens that man acts with a good intention, but without spiritual gain, because he lacks a good will. Let us say that someone robs in order to feed the poor: in this case, even though the intention is good, the uprightness of the will is lacking. Consequently, no evil done with a good intention can be excused. ‘There are those who say: And why not do evil that good may come? Their condemnation is just’ (Rom 3:8)’” (No. 78).12

[/vc_message][/vc_column][/vc_row]""""[vc_column_text]

“Let us say, if you agree, that if she leaves this situation, it will harm people. And then to avoid this evil, [says the woman] I continue in this union in which I already find myself.”

Note that the state of sin of the woman in question would hurt not only herself but also her companion—whom she assists in keeping away from God—and her children, who are influenced by their sinful situation. Additionally, a person’s actions affect not only their own external life but “give moral definition to the very person who performs them, determining his profound spiritual traits.” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 71).

Moral life cannot be separated from the practice of Faith, the spiritual life, and the supernatural perfecting of the soul.

“The Road to Hell Is Paved… ”

The intentionalism of the cardinal’s moral conception, insinuated above, becomes clearer below.

But it is well to recall the words of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux that “Hell is full of good intentions or desires,” which gave rise to the popular proverb, “The road to Hell is paved with good intentions.”

Pentin presents to the cardinal a text from the year 2000 issued by the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts—of which Cardinal Coccopalmerio is now president—about the interpretation of Canons 915 and 916 that forbid giving Communion to those who persist in manifest and serious sin, and asks whether that text is still in force.

The text reads:

“Any interpretation of Canon 915 that would set itself against the canon’s substantial content, as declared uninterruptedly by the magisterium and by the discipline of the Church throughout the centuries, is clearly misleading.”

While the cardinal answers in the affirmative, his interpretation of Canon 915 is intentionalist:

“It is always in force. [These canons apply to someone] [w]ho is in grave sin and says ‘I have no intention to change’: These are the Canons 915 and 916. But if someone says: ‘I want to change, but in this moment I cannot, because if I do it, I will kill people,’ I can say to them, ‘Stop there. When you can, I will give you absolution and Communion.’ Or also, I can insist on this intention of yours and say you are not in sin because you have the serious intention to change but at this moment you cannot do it. There are two things to put together. Understand?”

How Many Souls Will Lose Their Faith?

For Cardinal Coccopalmerio the mere intention of abandoning sin (without actually doing so) would suffice for the person to leave the state of sin. His intention plus the “impossibility” of abandoning sin would supposedly take away the sinful character of adultery or concubinage.

Now if you apply that principle to a thief who sustains his family with the products of his thievery, could one not say that he cannot leave that sinful activity because by doing so he would hurt his family and was thus forgiven for stealing? Would the same not apply to a drug or human trafficker?

“Simul Justus et Peccator”

Yet Cardinal Coccopalmerio continues his explanation insisting on the thesis that for a person to be forgiven and even sanctified the intention suffices, and no positive action is required.

“This person is already converted, is already detached from evil, but materially cannot do it. It’s a matter of caring for these situations.”

Human actions would thus be disconnected from their moral nature: a person with “good intention” can remain in sin because he “is already converted, is already detached from evil.”

What would the great penitent saints and the great authors on the spiritual life think about this? Can one at the same time disobey God’s Law and love Him above all things?

Did Our Lord Jesus Christ not say, “If you love me, you will keep my commandments”? And, “Whoever has my commandments and observes them is the one who loves me”?13

It is not the object of morals to make earthly life more comfortable. “Morals are not ordained to just any end but to man’s ultimate end, that is, that supreme value that transcends and subordinates to itself all other values and secondary ends, be they provisional or intermediary.”14

The doctrine expounded by the cardinal recalls Luther’s “Simul justus et peccator”—a Christian is at the same time both righteous and a sinner, according to which, one can sin without losing sanctifying grace and God’s friendship. The cardinal adds the necessity of having a “good” intention.

No Change of Life?—“You Absolve Him”

In his interview, Cardinal Coccopalmerio returns to the topic that good intention is sufficient to be forgiven, without abandoning sin:

“When someone comes to confess and says to you, ‘I committed this sin. I want to change, but I know that I am not capable of changing, but I want to change,’ what do you do? Do you send him away? No, you absolve him.”

In passing, let it be said that such absolution would be invalid because, as the Council of Trent teaches, in order for an absolution to be valid there needs to be “contrition, confession and satisfaction.” True contrition, the same Council explains, “is a sorrow of mind, and a detestation for sin committed, with the purpose of not sinning for the future.”15

Answering two questions of Edward Pentin, the Cardinal insists that the will to change is sufficient for the person to receive absolution and Communion:

“The sacraments are absolution and the Eucharist. The person does the same things, but he sincerely wants to change. Do you see there is an impossibility in this case? One cannot change immediately.”

As a consequence, having the mere desire to leave a sinful situation suffices for receiving Holy Communion. The person continues to sin but the act’s moral specification would change. On the other hand, the cardinal insists on the person’s impossibility of leaving sin, at least immediately.

To deny that a sinner is able to leave sin is to deny the efficacy of divine grace that God never denies a “contrite, humbled heart.”16

“To Change Their Intention, Not Their Style of Life”

Pentin asks, “Do they have to change their style of life before receiving Communion?”

The Cardinal replies, “No, they have to change their intention, not their style of life. If you wait until someone changes their style of life, you wouldn’t absolve anymore anyone at all. It’s the intention.”

Consequently, according to the cardinal, one must change the doctrine on the Sacraments because there is no longer anyone able to abandon sin…

And with that one understands better the doctrine of Amoris Laetitia.

Pentin: How do you recognize a true penitent?

Cardinal: “You have to pay attention to what the penitent says. If you know — you can tell if he is misleading you. But someone who comes to confession, already by the fact that he comes to confess, means he has the intention to change …. If I come to confess, it’s because I have a positive intention, even a small one, but serious, to change. You have to put all your attention on this intention. I’ll do all that I can.”

“The Companion Will Commit Suicide!”

Put against the wall by the interviewer on whether the martyrdom of Saint Thomas More and others who gave their lives for the indissolubility of marriage, Cardinal Coccopalmerio evades the question and takes on a dramatic tone:

“These people— take the women I spoke about in the book— say to everyone that marriage is indissoluble: ‘I am in a bad situation. But I would like to change it precisely because marriage is indissoluble. But at this moment I can’t do it.’

… But how can she leave the union? He [her civilly married spouse] will kill himself. The children, who will take care of them? They will be without a mother. Therefore, she has to stay there.”

One could ask why that man did not kill himself when his legitimate wife left him… As for the children, she would not need to remain in the state of sin in order to care for them. How many widows heroically care for their children, giving them the good example of virtue and entire dedication.

Declaration of Fidelity to the Church’s Teaching on Marriage

Amoris Laetitia as Interpreted by Cardinal Coccopalmerio

Having written a small essay to defend the Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitia and summarized his main argumentation in this interview, one can ask if Cardinal Coccopalmerio helped clarify the exhortation’s famous Chapter 8 from the standpoint of Catholic doctrine.

The answer can only be in the negative. Making it even more urgent that the Pope—instead of giving indirect approval of other’s explanations—give an official and clear answer to the critiques made to that Apostolic Exhortation. This is especially true regarding the questions raised in the Dubia presented by the four cardinals.

Our Lord Jesus Christ ordered the Apostles and their successors: “let your speech be yea, yea, no, no,” and warned, “that which is over and above these, is of evil.”17

In other words, something which is dubious, sibylline, confusing, does not come from Him Who said of Himself, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life,” but rather, from the evil one.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Footnotes

- All emphasis ours.

- Cf. Orazio La Rocca, “Papa Francesco e i divorziati: la risposta ai cattolici intransigenti,” Panorama, February 10, 2017, at http://www.panorama.it/cultura/libri/papa-francesco-e-i-divorziati-la-risposta-ai-cattolici-intransigenti/ (all emphasis ours). Accessed March 17, 2017.

- Cf. Arnaldo Vidigal Xavier da Silveira, “Acts, Gestures, Attitudes and Omissions Can Characterize a Heretic,” in Can Documents of the Magisterium of the Church Contain Errors? (Spring Grove, Penn.: The American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property—TFP, 2015), p. 47-72. (If not stated to the contrary, all emphasis in this article is ours).

- Cf. Catholic Voices Comment, “Buenos Aires bishops’ guidelines on Amoris Laetitia: full text” of September 18, 2016: “Guidelines on implementing Amoris Laetitia written by the bishops of the pastoral area of the Argentine capital, Buenos Aires, … [on] Chapter 8 of Amoris Laetitia in their pastoral practice, namely, the part of the Pope’s document on the family and marriage that refers to access to sacraments for the divorced and remarried.

“After receiving the guidelines on September 5, Pope Francis wrote back approvingly. ‘The document is very good and completely explains the meaning of Chapter VIII of Amoris Laetitia,’ he told them, adding: ‘There are no other interpretations.’” at https://cvcomment.org/2016/09/18/buenos-aires-bishops-guidelines-on-amoris-laetitia-full-text/. Accessed March 17, 2017. - Cf. Orazio La Rocca, “Papa Francesco e i divorziati: la risposta ai cattolici intransigenti,” Panorama, February 10, 2017, at http://www.panorama.it/cultura/libri/papa-francesco-e-i-divorziati-la-risposta-ai-cattolici-intransigenti/, accessed March 17, 2017.

- Edward Pentin, “Cardinal Coccopalmerio Explains His Positions on Catholics in Irregular Unions,” National Catholic Register, March 1, 2017, accessed March 17, 2017.

- In his book, Cardinal Coccopalmerio gives the same example. Cf. Inés San Martín, February 14, 2017, “Vatican’s legal chief says desire to change enough for Communion,” at https://cruxnow.com/global-church/2017/02/14/vaticans-legal-chief-says-desire-change-enough-communion/ accessed March 17, 2017.

- “There are those who say: And why not do evil that good may come? Their condemnation is just” Rom. 3:8.

- “Litany of St. Michael the Archangel,” at https://www.saint-mike.org/library/litanies/stmichael.html, accessed March 17, 2017.

- Encyclical note: Cf. Summa Theologiae, I-II, q. 18, a. 6.

- Encyclical note: Cf. Ecumenical Council of Trent, Sess. VI, Decree on Justification Cum Hoc Tempore, Canons 19-21: DS, 1569-1571.

- Encyclical note: In Duo Praecepta Caritatis et in Decem Legis Praecepta. De Dilectione Dei: Opuscula Theologica, II, No. 1168, Ed. Taurinen. (1954), 250.

- John 14:15; 21.

- Antonio Lanza-Pietro Palazzini, Principios de Teologia Moral (Madrid: Rialp, 1958), I, p. 17, emphasis from the original.

- Council of Trent, Session IV, Chap. 3 and 4, Denzinger Nos. 896-897.

- Ps. 51:19.

- Matt. 5:37.