France was once defined by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand as a nation of one religion and 500 cheeses. By way of contrast, he defined America as a country with one cheese and 500 religions. While the French diplomat might have been accurate about religion in America, his assessment of America’s cheese-making abilities was entirely incorrect. For some time now, American “artisans,” as they are called, have been producing world-class cheeses that rival those of France, and by doing so, they prove that Kraft is not the only game in town. To find them however, we must get off the beaten path.

France was once defined by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand as a nation of one religion and 500 cheeses. By way of contrast, he defined America as a country with one cheese and 500 religions. While the French diplomat might have been accurate about religion in America, his assessment of America’s cheese-making abilities was entirely incorrect. For some time now, American “artisans,” as they are called, have been producing world-class cheeses that rival those of France, and by doing so, they prove that Kraft is not the only game in town. To find them however, we must get off the beaten path.

Cheese History

An artisan is someone who uses distinctive or original recipes to make cheese in small batches by hand. They are comparable to those who might produce a piece of furniture or clothing that has a unique design. Their artistry is comparable to bees who extract the sweet nectar from local flowers in order to produce honey that is particular to a certain area.1

In the case of American cheese makers, their creativity results in a product that is refreshingly home-made and is the result of a tradition that dates back to the early seventeenth century. It was then that farms on the East Coast, most especially New England, began making cheese. It had been a predominantly at-home or on-the-farm industry because the milk had to be consumed quickly or processed in other ways. The cream which floated to the top was used for butter leaving what was left — skimmed milk — for making cheese.

Until the early 1800’s, there was no such thing as a cheese factory because there was simply no need for one. With the influx of European immigrants and the sudden growth of America, all that changed. Civilization and the cheese-making craft eventually moved west towards the Great Lakes. What started out small would become a quite large industry.

Cheese factories, often family operated, began popping up all over Wisconsin where the cow population kept pace with humans. It was not long until the railroads reached this region and along with it came a greater demand for cheese. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, cheese factories continued to multiply across southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois.

In 1903, a Canadian-born businessman named James L. Kraft started a wholesale cheese business in Chicago. After a bumpy start, the company would go on to develop thirty-one varieties by 1914. Two years later, Kraft invented a way to pasteurize cheese that eliminated the need for refrigeration. He was granted a patent for a product that came to be known as processed cheese.3 Thus the “one-cheese” myth was born.

What most people do not know is that while some companies were sacrificing quality for quantity, others were not.

Cheese Artisans of America

Ig Vella was only three and a half when his father, Thomas “Gaetano,” opened Vella Cheese Company in 1931. He vividly remembers the trips to San Francisco, with his father, to help throw the cheese wheels out the back of the family’s truck.

Both Thomas and his young son personally knew J.L. Kraft who, at that time, was using a horse and buggy to distribute cheese. Mr. Vella points out that “a lot of people started trying to make cheese but got out of the business because they realized it was spelled W-O-R-K.”

“There are still people trying to cut corners,” he continued, “especially on the raw milk cheese varieties.” Mr. Vella does not cut corners and his attention to detail has paid off. He remembered very vividly when he made his first Asiago, a cheese named after the town near Venice. An Italian couple came into his store and sampled a bit. “This is better Asiago than we get back home in Italy,” they both commented.

Visitors from Toma, Italy, had the same surprise when they entered the store and sampled Mr. Vella’s Toma cow’s milk cheese, originally developed in their region of Italy. Overcome by the taste of the American version, they exclaimed, “Molto buono, molto buono [very good].”

While European visitors rave over what they discover in America, Mr. Vella is not surprised. “We just never got the recognition for the quality of our cheeses, especially in the last 25 years — but we have always been there,” he adds with emphasis.

American “Somewhereness”

The secret to great American cheeses is actually no secret at all. The success they enjoy comes from their ability to take advantage of the rich resources offered in their particular region. It is what author Rowan Jacobsen calls terroir, a French word that means “taste of place.” He is the author of American Terroir4 and describes how such creativity is “anathema to a certain conservative European school of gastronomes, who believe that the Land of the Golden Arches is incapable of producing foods and drinks that embody a particular ‘somewhereness.’”5 He affirms that the American version of terroir rivals that of Europe.

Al and Catherine Renzi are but one example. They started Yellow Springs Farm in Chester Springs, Pennsylvania ten years ago and later discovered the horticultural riches of the land they owned after doing a botanical survey. This eventually led to a plant nursery and later a few goats which Mrs. Renzi defined as just a “friends-and-family thing.” Over the years, they were able to get a permit from the PDA (Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture) to make and sell goat cheese. They have come a long way since then and are now members of both the American Cheese Society (ACS) founded in 1983 and the Chester County Cheese Artisans.

Their Red Leaf cheese won an ACS award in 2010 while their Nutcracker took first place. Red Leaf is actually wrapped in sycamore leaves that grow on their property. Both cheeses, she says, are examples of their intent to integrate the horticultural plant richness of the landscape with the cheese.

The interest in local food in America, she went on to explain, is encouraging people to understand that just as the French have their great cheeses, so does America.

“They are as unique and varied,” she continued, “as our local indigenous botanical resources, micro climates, histories and cultures. That is really the essence of why there can be a Chester County Cheese Artisan. We have the richness of sycamore and black walnut trees and that’s what makes our cheese special. It is what our goats eat. It’s the geology of the land that produces the herbaceous layer of pasture they stand on. It’s the weather, the climate, the air.”

There is a long history of what she defined as a “dairy heritage” in this area and it embraces everything from Breyer’s ice cream to Philadelphia cream cheese.

“France is in trouble”

The Renzis went to Italy and met with a lot of cheese makers who were more than willing to share their recipes. However, they were told that a recipe alone is not what makes good cheese.

Your cheese will never turn out like ours, the Italians said, because you have different goats which eat different foods. You have different climate, air, water. You are different. Your essence of being is different. In final analysis the Renzis were told to go home and “make your own cheese.”

In this way, the Americans learned more than the art of making good cheese and acquired a valuable lesson in organic society which respects regional differences. This is very good news for cheese lovers since France, always known for its great cheeses, is actually in decline. Mr. Jacobsen attributes this to the eating habits of the newer generations which are changing. “French consumers,” he says, “are going to the supermarket.”6

American cheese maker Mateo Kehler found this out first hand when he last visited France. He and his brother Andy are producing world-class cheese at their Jasper Hill Farm in Greensboro, Vermont. He spoke with French cheese-maker Herve Mons who affirmed that terroir in France “has been defined” and is actually in decline.

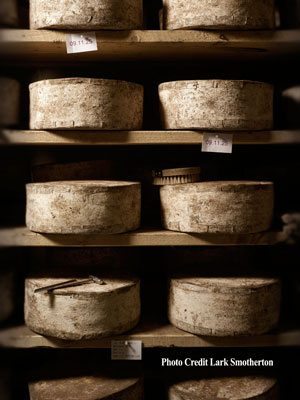

During that trip, Mr. Kehler presented his Winnimere cheese to a top French affineur to get his opinion. An affineur is a person who oversees the affinage or aging process of cheese making. Fifty percent of what one tastes in the final product is the result of proper aging. It is for this reason that cheese makers will often send their cheeses to the best affineurs, even if it means sending their cheese to the other side of the country.7

After taking one taste of Jasper Farms products, the French affineur was forced to admit, “no such cheese has been made in France for thirty years.” Mr. Kehler presented the same cheese to a French consul-general — the man charged with furthering French culture abroad. The stunned Frenchman tasted the cheese, looked up and said, “France is in trouble.”8

Jasper Farms is not the only cheese maker turning heads abroad.

Capturing the Gold

Rebecca Sherman Orozco is the communications director for American Cheese Society and told me about the World Championship Cheese Contest which is held every two years.

“Overall, U.S. cheese makers dominated the competition,” she said, “earning gold medals in 46 of the total 77 categories judged.” Wisconsin dominated with twenty-one gold medals. One of them went to Carr Valley Cheese in La Valle, Wisconsin, which is one of the oldest producers in America.

You may not have heard of it but Carr Valley has been around since 1902 and therefore predates Kraft. Its website describes the producer’s “passion for cheese-making excellence” that runs deep. Today, fourth-generation owner Sid Cook is one of a small handful of certified American master cheese makers. This distinction is only awarded to veteran Wisconsin craftsmen who complete a rigorous fifteen-year advanced training and education program.9

At the 2012 World Cheese Awards held in the United Kingdom, Jasper Hill captured the gold for its Harbison cheese, against over 2300 other cheeses from all over the world.

The success which American cheese artisans enjoy is no surprise to Mrs. Renzi of Yellow Springs Farm. When I asked her opinion of Talleyrand’s comment on cheese in America, her response was simply, “Things have changed.”

Actually, no, they haven’t. Great cheese makers have always existed in America. They are proof that within a land that appears to only offer universal sameness, one finds wonderful examples of American somewhereness. This is yet another marvelous example of the regionalism that can be found when one gets off the beaten path.

Footnotes

- John Horvat, Return to Order, York Press, p. 208.

- http://www.kraftfoodscompany.com/ca/en/about/history.aspx{/ ref} The American military bought six million pounds for the troops fighting in World War II.2http://www.successful-stock-trading.com/kraft-foods-stock.html

- http://www.amazon.com/American-Terroir-Savoring-Flavors-Waters/dp/B004TE8FP0/ref=la_B001IOBDH6_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1364936652&sr=1-2

- Rowan Jacobsen, American Terroir, Bloomsbury USA, pp. 2-3.

- Rowan Jacobsen, Pg. 233

- ttp://www.slashfood.com/2008/07/04/whats-affinage-and-whos-the-affineur/

- Rowan Jacobsen, Pg. 233

- http://www.carrvalleycheese.com/