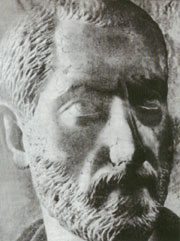

look of a man accustomed to analyzing the world with a truly admirable sense of calm.

If we compare the features of this third-century Roman, represented in a splendid sculpture from the Capitoline Palace, with those of the famous Apollo Belvedere, its irregularities become evident. In this sense, we could not exactly call this man handsome.

Nonetheless, no one can deny that his countenance possesses a certain element of beauty, mainly a moral beauty. The contours of the face and skull are well proportioned. All of his features are balanced, strong, and regular, and all find their highest and most vivid expression in his gaze. It is the lucid, calm, and serious look of a man accustomed to analyzing the world with a truly admirable sense of command and with confidence in his own abilities. It is a look that reveals a soul of manly temperament, capable of confronting the trials and uncertainties of life with strength and nobility.

Such is the character of the Roman soldier, as we know from history. He had those qualities that enabled him to spread Rome’s great accomplishments: the Empire, law, literary and artistic masterpieces.

In the same third century, Saint Sebastian served as the commander of the imperial bodyguard under the Emperors Diocletian and Maximilian. This guard comprised the army’s elite and, for the people of Rome, embodied the ideal of manliness.

We know of no existing document that describes the actual features of this glorious martyr, but everything leads us to believe that he would have been even stronger and more serious than the anonymous Roman in the first picture.

This is so because Saint Sebastian was a Catholic. Grace, which elevates and fortifies nature, would, far from weakening the virtues of the Roman, render these same virtues incomparably greater.

How, then, could the noble Praetorian officer of the guard resemble this youth, who, while riddled with arrows, looks the very opposite of Christian mortification, fortitude, and seriousness?

The painting presents a youth comely of face and body, quite assured of his good looks and satisfied with showing them off. His face has a sentimental and capricious expression. His posture is that of one who, though somewhat weary of standing, indolently enjoys the sun and the breeze. The tree serves him as a convenient prop, and he adroitly manages to support his feet comfortably on two sawed off stumps. The arrows cause him not the least pain. Nothing in his person conveys the impression that he is going to die. Thoughts of God and of eternal life, a prayer for final perseverance, prayers for Holy Church, a vigorous rebuke or a word of kindness to his torturers – none of this is expressed or represented in the picture.

One could say that this youth, bored with being alone, merely waits for someone to find him and return him to his everyday life. In short, this is a morally mediocre figure, concerned exclusively about himself – and with the world insofar as it affects him. He belongs to the moral family of banal souls.

Artistically, the work is a masterpiece, ascribed to the immortal brush of Botticelli. But the master should not have titled it Saint Sebastian. Rather, he should have left out the arrows, placed the youth on the ground, and called the work Vain Young Man Basking in the Sun.

Why these comments? To help us perceive all the evil that the pagan Renaissance caused to souls by spreading an impalpable but contagious state of mind through its art, a state of mind that discreetly contradicted all the ideas of the Church about moral perfection.

Furthermore, it is a warning for Catholics in face of the much more serious deviations and aberrations of numerous modern artists!