There are few places on Earth more beautiful than Hawaii. While this idyllic paradise may be the destination spot for tourists and honeymooners, Joseph de Veuster was eager to go there for a completely different reason. It was Joseph’s missionary zeal that attracted him to Hawaii where he volunteered to care for those stricken with leprosy. He eventually contracted the disease and died a painful death. The world would come to know him simply as Father Damien the Leper priest. On October 11, 2009, he was canonized a saint by the Catholic Church and will be remembered throughout history as a heroic example of Christian compassion.

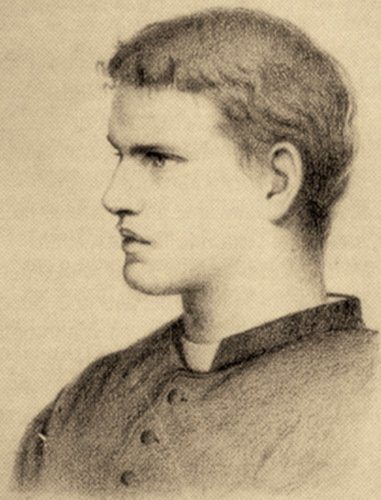

Father Damien sensed from early on, in his vocation, that he was not called to a common missionary life. He dreamed of doing apostolate among the savages. After joining the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in his native Tremeloo, Belgium, he prayed daily before an image of Saint Francis Xavier for this intention.

After completing his studies, he was sent to the Hawaiian Islands in March 1864 and was ordained a priest some months later at Our Lady of Peace Cathedral in downtown Honolulu. His first years on the archipelago were spent primarily on the Big Island of Hawaii, but it was not long before fortuitous events prepared the way for the fulfillment of his life’s dream.

The first occurred in 1865 when an epidemic of leprosy threatened to wipe out the native Hawaiian population. Seeing no other option than quarantine, the Hawaiian Legislature and King Kamehameha V signed a decree banishing the lepers to a neighboring island.

A “Royal Soul” Goes to Kalawao

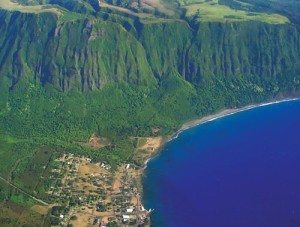

The mere mention of Molokai was enough to send shivers up the spine of nineteenth century Hawaiians. This island, located just southeast of Oahu, became the final destination and burial place of over 8,000 Hawaiians diagnosed with the terrible disease. The first settlement, where Father Damien spent most of his time, was established in the village of Kalawao located on the eastern side of a peninsula that protrudes off the northern coast of Molokai.

The first lepers to arrive found dreadful living conditions. There was very little food and shelter, inadequate medicine and absolutely no hope. Many lepers refused to leave the boats that docked on the tiny island of Okala, just offshore from Kalawao, and were thrown overboard. Those who could not swim drowned in the turbulent Pacific Ocean.

They were sent there to die and they knew it. Seeing themselves abandoned in such a callous way, they gave themselves up to all sorts of vices. Treated like animals, they quickly began to act like animals. Losing all human joys, they feverishly grasped at those of the beasts and subsequently gave themselves over to a sinful life.1

Those in Honolulu who were spared the disease grew increasingly indignant with the neglect of the lepers. On April 15, 1873, an impassioned plea for a sacrificial soul appeared in a Hawaiian newspaper. “If a noble Christian priest, preacher or sister should be inspired to go and sacrifice a life to console these poor wretches,” it read, “that would be a royal soul to shine forever on the throne reared by human love.”2

On May 4, 1873, Bishop Louis Maigret, the vicar apostolic, realizing the lepers needed stable spiritual support, asked for a volunteer among four Sacred Hearts Fathers, for the Molokai mission. Father Damien was chosen and accepted what was virtually a death sentence with joy and resignation. “Remember that I was covered with a funeral pall the day of my religious profession,” he said, “here I am, Bishop, ready to bury myself alive with those poor unfortunates.”

Suffocating Melancholy and Unbearable “Black Thoughts”

Amid the generalized chaos of the inhabitants of Kalawao, there were a group of Catholic lepers who remained steadfast. When Bishop Maigret and Father Damien arrived on May 10, 1873,3 they were met by this group who had rosaries dangling from their necks. Unable to contain their joy, they threw themselves at the bishop’s feet in tears.

Father Damien wasted no time in spreading a blanket of hope where there had previously been only despair. He spent the first weeks at Kalawao building proper housing for the homeless.

“Remember that I was covered with a funeral pall the day of my religious profession,” he said, “here I am, Bishop, ready to bury myself alive with those poor unfortunates.”

During this time he slept under a pandanus tree, which grows on rocky soil and attracts scorpions and other undesirable creatures. He refused to sleep under a roof when the lepers he went there to serve had none.

This suffering was mild compared to the spiritual hardships he would endure. For most of the time he spent on the peninsula, he was alone. He pleaded for a confessor but often went as long as five months without seeing another priest. During that time, he spoke of a suffocating melancholy that caused him unbearable “black thoughts.”

On one occasion, a supply ship with a priest on board stopped offshore. In hopes of making a confession, Father Damien took a small boat out to meet the vessel. The captain feared contagion and thus refused to let him board. Not allowing this to deter him, Father Damien humbly screamed his sins, before receiving absolution from the priest above. Years later, that same captain converted to the Faith and admitted doing so because he was so touched by the scene.

Giving Them a Sense of Purpose

Father Damien possessed herculean strength and refused to let these trials depress him. He was known to carry out his apostolic endeavors with a boundless energy, an iron resolve and a childlike enthusiasm. His good deeds were the most varied imaginable.

and organized a choir for Mass, and a band whose members played instruments he made by hand.

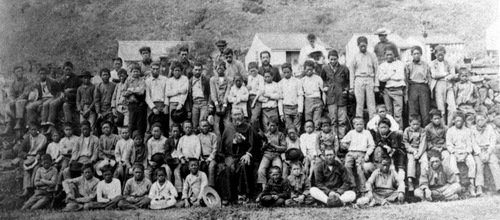

Besides taking care of his priestly responsibilities, he also found time to organize a choir that sang for masses held in Saint Philomena’s Church that he built. This zealous priest also organized a band whose members played instruments he made by hand. He taught them to farm, raise animals and assist in building everything from cottages to the coffins4 used in funerals held daily. Besides making their coffins, Father Damien also assisted in digging their graves.

What the lepers most admired about Father Damien, however, was his heroic ability to overcome the natural revulsion for their disease. On one occasion, he was hearing the confession of a woman whose side had been eaten away by maggots, thus exposing her intestines and rib cage. The holy priest tranquilly absolved her sins with the same intestinal fortitude with which he treated her wounds.

People were amazed at the gentility with which he cared for the sick. One witness said he saw Father Damien “bandage the most frightful wounds as though he were handling flowers.”5 On other occasions, he was even forced to amputate rotting limbs that emitted a foul odor. This, along with their breath, which Father Damien said would “poison the air,” caused him an almost “unconquerable nausea” and “headaches that lasted for days.” It is for this reason that he took up smoking6 to combat the stench surrounding the sick and dying when he administered their sacraments. It also purged the foul odor from his clothes once he had left their presence.

His Christ-like love for the lepers allowed him to conquer his nausea in record time. Two weeks after his arrival, he wrote in his diary how all his “repugnance toward the lepers has disappeared.”7

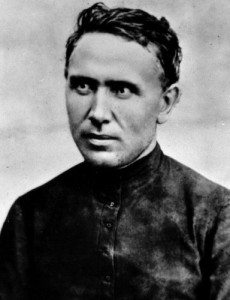

Photo taken by William Brigham.

Combating “Leprosy of the Soul”

Stories such as these might lead some to consider Father Damien a humanitarian whose only desire was to alleviate physical suffering. What troubled him most, however, was not the leprosy of the body, but rather what he called “leprosy of the soul.” As a true missionary, his primary concern was the spiritual well-being of his parishioners that gave him the wisdom to instruct each according to their needs.

“In one place I speak only gentle, consoling words,” he explained, “in another I have to be harsh, to stir the conscience of some sinner; at times I have to thunder and threaten unrepentant sinners with eternal punishment.”8

Such was the case when Father Damien encountered a man making a visit to one of the active volcanoes on the Big Island, which the locals worshipped as a “god.” They interpreted each eruption as a sign of an angry deity that needed appeasement. Witnessing such foolish paganism, Father Damien stopped the man long enough to give him a short sermon on hell9 as the two of them contemplated the molten lava that danced before their eyes.

“In one place I speak only gentle, consoling words. In another I have to be harsh, to stir the conscience of some sinner; at times I have to thunder and threaten unrepentant sinners with eternal punishment.”

On other occasions, his zeal for souls drove him to go beyond mere words in his fight against the sin of impurity. It was the custom among some impenitent lepers to participate in drunken festivals while they danced to the uli-uli, a drum made from a large gourd. The beat of this instrument created the rhythmic cadence of the native hula. The dancing and drinking invariably degenerated into sordid acts of debauchery that often included children.

Father Damien made war against such depravity by making regular walks around Kalawao, cane in hand, listening for the distinctive sound of the uli-uli. If the culprits saw him approach, they fled in terror because they knew what was coming. When he caught them unaware he entered the spiritual “battlefield” swinging his cane, breaking cups, smashing gourds and bruising flesh. He made it crystal clear that his love for them was not of the sentimental type so common in the modern world.

Died Like a “Child Going to Sleep”

It was not long before Father Damien succumbed to the terrible scourge of leprosy. His custom shortly after arriving on Molokai was to address his parishioners by saying “we lepers” even before he showed signs of having contracted the disease. By burying himself on the island, and doing so without the slightest fear of touching and caring for them, he became a leper. This was confirmed in 1884 when he was soaking his feet in scalding hot water without feeling any pain.

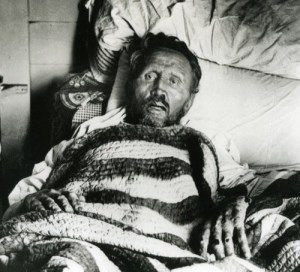

Photo taken by Sidney Bourne Shift.

During the remaining years of his life, he continued to work hard, but with much greater effort. The five-minute walk to the hospital for a man who used to enjoy perfect health now caused him so much pain and fatigue that he would cry all night.10 Yet he never quit.

In 1888, a terrible storm passed through Kalawao and destroyed the steeple atop Saint Philomena’s Church. Despite his frail health, Father Damien organized a crew to replace it. Father Corneille Limburg was there during the later part of the year and was astonished to see our saint “in the thick of it, on top of the church, in fact, putting on the roof.” The visiting priest went on to describe this victim whose leprosy was far advanced: His face was puffy, the flesh on one of his ears was broken, his eyes were red and his voice hoarse. Father Limburg continued,

You should have seen the wild activity he was directing, giving his orders, now to the masons, now the carpenters, now to the laborers, all lepers. You would have said he was a man in his element and perfectly healthy. This tells you that Father Damien seems not to want to stop until he falls.11

A few months later, Father Damien was on his deathbed. After receiving Holy Communion “like a seraph”12 on the morning of April 14, he died the following day, “like a child going to sleep.”13

He was buried under the same pandanus tree, outside Saint Philomena’s Church, under which he had slept upon his arrival to the peninsula.

Among Saint Damien’s biggest admirers were the last two queens of Hawaii, Esther Kapiolani and Lydia Liluakolani. In striking contrast to the Revolutionary way monarchs are historically portrayed, these great ladies visited the colony several times and were received by the lepers like the mothers they were.

One of the holy priest’s biggest detractors was the Presbyterian minister Charles McEwen Hyde. He made the mistake of calumniating Saint Damien in a letter where he described the hero of Molokai as a “coarse, uncouth, dirty man” who contracted leprosy through his own “carelessness.” This letter, written four months after the saint’s death, was eventually published in the English Churchman and was later widely reproduced.

This injustice provoked the anger of fellow Presbyterian and world-renowned author Robert Louis Stevenson who happened to be visiting Hawaii at that time. Mr. Stevenson took it upon himself to write a refutation that turned out to be perhaps the most objective eulogy of the saint one can find. He then paid to have it published in an English newspaper before it spread throughout the entire world.

In it, he points out the battlefield upon which Saint Damien gave his life and eloquently contrasted it with the comfortable life chosen by the Reverend Hyde.

“When we sit and grow bulky in our charming mansions,” Mr. Stevenson said, “and a plain, uncouth peasant steps into the battle, under the eyes of God, and succors the afflicted, and consoles the dying, and is himself afflicted in his turn, and dies upon the field of honor — the battle cannot be retrieved as your unhappy irritation has suggested. It is a lost battle, and lost forever. One thing remained to you in your defeat — some rags of common honor; and these you have made haste to cast away.”14

Thanks to Mr. Stevenson and devout Catholics the world over, Saint Damien will never be forgotten. He will always be remembered as a man who went to the most beautiful place on earth in order to care for the most hideous of God’s creatures. In so doing, he became a hero who died on the battlefield of honor.

Footnotes

- Vital Jourdain, SS.CC., The Heart of Father Damien, 1840 – 1889 (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1955), 90.

- Ibid., 93.

- The feast day assigned to Saint Damien.

- “Damien the Leper,” http://www.ewtn.com/library/MARY/DAMIEN.HTM.

- Vital Jourdain, SS.CC., The Heart of Father Damien, 1840 – 1889 (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1955), 142.

- Gavin Daws, Holy Man: Father Damien of Molokai (University of Hawaii Press, 1989), 83.

- “Building a Community — Starting from Scratch (1873 – 1876),” http://www.damienmolokai.com/node/171.

- Vital Jourdain, SS.CC., The Heart of Father Damien, 1840 – 1889 (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1955), 179.

- Ibid., 47.

- Gavin Daws, Holy Man: Father Damien of Molokai (University of Hawaii Press, 1989), 157.

- Ibid., 199.

- Ibid., 211.

- Vital Jourdain, SS.CC., The Heart of Father Damien, 1840 – 1889 (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1955), 375.

- Robert Louis Stevenson, “Father Damien — An Open Letter to the Reverend Dr. Hyde of Honolulu, February 25, 1890,” http://www.fullbooks.com/Father-Damien.html.