In 1878, Pope Leo XIII ascended to the papal throne. The following year, Pope Leo elevated Father Newman to the cardinalate. Thus, the two men who most influenced the formation of nineteenth-century English Catholics, Manning and Newman, had become Cardinals of the Holy Church. In this capacity, both men could use their prestige as Princes of the Church to propagate their ideas.

Given Newman’s advanced age, the pope authorized him to continue residing in England, even though he was assigned to the Curia. Cardinal Newman dedicated himself to studying and reviewing his work until his death in 1890. To posterity, he bequeathed the fruit of a life devoted to intelligence. His life was marked by the glory of being one of the founders of the Oxford Movement, from which came great converts who gave life to nineteenth-century English Catholicism.

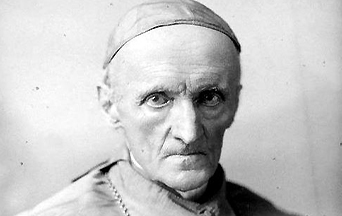

Somewhat younger and more active, Cardinal Manning continued his fruitful apostolate. He was always faithful to orthodoxy. He never diluted his principles to attract sympathy, nor did he give up the rights of the Church to escape difficulties. He inspired Catholics with zeal and enthusiasm, throwing them into the work of restoring the true Religion to his homeland. Despite Protestant prejudices against him, his rectitude, energetic personality, and indefatigable apostolate won the sympathy of English public opinion. These qualities earned him a prominent position in British society that owed nothing to great politicians of the time, Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

In June 1890, Manning completed 25 years as a bishop. Great feasts were prepared to celebrate the jubilee. They were a genuine apotheosis. The whole nation applauded the great Englishman who raised England in the eyes of world opinion. Catholics joyfully expressed gratitude to the pastor who guided them with a firm and sure hand for a quarter of a century. The Cardinal entered the ceremony held in his honor in the archbishop’s noble hall, led by the Lord Mayor of London. His clergy and laity, as well as the Irish, praised a life so full of toil and triumph. Responding to the Irish, the archbishop could not help recalling the glorious past of the land of Saint Patrick. After declaring that every drop of his blood was English and that he loved England as a child of her soil, he continued: “As for Ireland, I love her not only for her kinship with England but also for her faith and the martyrdom she endured.”

The Duke of Norfolk greeted him on behalf of the laity. In reply, the Cardinal gave an admirable account of himself. He recalled that he had dealt with many people about many things. Then he added: “It is impossible that some of my actions have not incurred the disapproval of many or personally displeased others. Your affection has covered all that with silence. Now, about to account to God for my life, I declare that I have not voluntarily offended anyone.” Shortly before his death, he wrote in his diary, “I am not conscious of having allowed any pebble or even grain of truth to be lost.”

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

London dock workers joined the celebrations by taking a collection among themselves. They thus expressed gratitude for the Cardinal’s intervention in their famous 1889 strike. Moved, Cardinal Manning applied the amount to the foundation of a hospital for victims of work accidents. His prestige in working-class circles led the Protestant newspaper Echo to lament that the official Anglican Church had no one capable of achieving such popularity, which it credited to his boundless devotion to improving people’s living conditions.

Sensing death approaching, Cardinal Manning piously prepared for it. Having begun a diary in 1880, he recorded those thoughts suggested by his meditations. He also wrote of his appreciation for people and events throughout his life. He made careful examinations of conscience. We know from this document that, to him, no cross seemed as heavy as being opposed— especially in his diocese—much more by Catholics than by the Church’s enemies.

Manning died on January 14, 1892, eighteen months after Newman. Toward the end, his health no longer allowed his prodigious activity of yore, but he continued to govern the diocese firmly. In early 1892, he became weaker. On January 13, he asked for Extreme Unction. The next day, as Msgr. Herbert Alfred Henri Vaughan, who would become his successor, celebrated Mass at his bedside, the Cardinal serenely surrendered his soul to God.

Representatives of Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales, as well as countless ecclesiastical dignitaries, the entire diplomatic corps, members of the aristocracy, England and Ireland’s best-loved personalities and a vast crowd, led him to the tomb. As the coffin passed, countless people knelt and prayed. England once again consecrated the apostolate of the great Cardinal Manning.

Science Confirms: Angels Took the House of Our Lady of Nazareth to Loreto

Expressing the nation’s grief, one of the speakers said that the death of the two cardinals ended an era, making way for another. In fact, the disappearance of the two men who most influenced the formation of the Catholic movement in England ended the legal prejudice against the Church’s rights in the country during the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, the consolidation of these efforts would begin.