On the 150th Anniversary of Two Events of Transcendental Significance for the Life and History of the Church

The year 2020 marks the 150th anniversary of two events of transcendental significance for the Church’s life and history. The first is a positive event, which was the proclamation of the dogma of papal infallibility (July 18, 1870). The second event was a negative episode, which was the taking of Rome by the revolutionary hordes at the service of the House of Savoy. At that time, the Pope was despoiled of his temporal power (September 20, 1870).

This short article will put the two events in the context of the life and pontificate of their main protagonist, Blessed Pius IX, the last Pope-King.

The conclave that met on June 15, 1846 to elect a successor to Gregory XVI was one of the shortest in history: it lasted only 36 hours, after which Cardinal Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti, Bishop of Imola, was elected and adopted the name of Pius IX.

The first acts of his pontificate, especially the choice of his closest advisors and the release of hundreds of political prisoners, left his contemporaries perplexed.

Was Pius IX a liberal?

This question has been asked by historians1 and the answers have varied.

Some see him as a liberal who—mugged by reality—converted, becoming a “reactionary.” Others present him as a pragmatic diplomat who made a miscalculation when he thought he could placate the revolutionaries with a policy milder than his predecessor, the austere and energetic Gregory XVI. Still others say that he was not a liberal and that his policies, permeated with clemency and liberality, were dictated more by his conciliatory temperament than by ideology, and that the Revolution sought to take advantage of this, appointing him as a “liberal” Pope, ready to carry out its designs.

Whatever the answer, the fact is that, as soon as Pius IX cleared up the misunderstanding and energetically put an end to the revolutionary consequences they intended to draw from his acts, everything changed. The revolutionary sectarians responded by inciting the Roman populace to mutiny. The mobs stoned the Pontifical Palace, and the Pope had to leave the Eternal City secretly, taking refuge in Gaeta in the Kingdom of Naples. Meanwhile, the revolutionaries stalked the streets of Rome, sowing terror through an orgy of blood and desecration of churches and convents. Finally, they declared the civil power of the Pontiff to be over and proclaimed the “Roman Republic.”

The Pope appealed to Catholic powers, which uprooted the revolutionaries from Rome and the other pontifical territories. After a few months, Pius IX returned to his capital.

* * *

However, the Revolution was determined to end the temporal power of the Popes forever by unifying Italy. Controlling a centralized State is easier than coercing the various small local sovereigns of the Italian peninsula, which included the Pope, the Kings of Piedmont and Naples, the Grand Duke of Tuscany and the Dukes of Modena and Parma.

Thus, Piedmont troops occupied several provinces of the Papal States. On March 26, Pius IX issued an excommunication “against all usurpers of the Church’s possessions.”

The Pope was left with only Rome and the surrounding Patrimony of Saint Peter, which he was willing to defend by arms. This time the Catholic powers did not heed his appeal, so Pius IX addressed the faithful worldwide. Young and old, noble and plebeian, men rushed to fight for the Pope. They wrote one of the most glorious pages in the history of the Church, immortalized by the legendary figure of the Papal Zouaves. These soldiers were the personification of honor and courage, faith and detachment. However, their value did not prevent them from being crushed by the incomparably superior number of an adversary that was better armed and equipped.

* * *

But Pius IX was not a man to be bent by the force of arms. Amid all these tribulations, he continued to rule the Church with wisdom and courage. He faced even tougher battles that might be called hand-to-hand struggles, against the declared or disguised errors, the external foes or internal enemy, which are a hundred times more dangerous.

Three moments of this arduous and incessant thirty-year struggle deserve to be highlighted: the definition of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin; the Encyclical Quanta Cura with the Syllabus; and, finally, the First Vatican Council with the proclamation of Papal Infallibility.

“I am the Immaculate Conception”

Pius IX was an eminently Marian Pope. He consecrated his pontificate to the Blessed Virgin. As soon as Providence entrusted him with the Keys of Saint Peter, he manifested his intention to proclaim the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of the Mother of God. The general longing of Christian piety favored this proclamation. From ancient times, bishops and religious orders, emperors and kings, and entire nations appealed to the Apostolic See to define this universally accepted truth as a dogma of the Catholic faith.

Before agreeing to this welcome wish, the Pope wanted to hear the opinion of the theologians and consult the sentiments of the faithful in the Catholic universe. He established a commission of cardinals and theologians, commissioning them to study the matter diligently. He wrote to all the world’s bishops, inquiring about the piety and devotion of the faithful of their dioceses to the Immaculate Conception of the Mother of God. Each bishop was asked his opinion about the projected definition. The unanimous favorable responses made the Pope feel that the time had come to proclaim this prerogative of the Blessed Virgin solemnly.

In the presence of more than two hundred cardinals, archbishops and bishops from all over the Catholic orb, Pius IX signed the Bull Ineffabilis Deus on December 8, 1854. In it, he declared, pronounced and defined as a doctrine revealed by God and a truth of Catholic faith “that the most Blessed Virgin Mary, in the first instance of her conception, by a singular grace and privilege granted by Almighty God, in view of the merits of Jesus Christ, the Savior of the human race, was preserved free from all stain of original sin.”

The Queen of Heaven and Earth showed how pleased she was with Pius IX’s definition. Our Lady appeared on February 11, 1858, in Lourdes to the humble Bernadette. When the little girl asked who she was, Our Lady answered: “I am the Immaculate Conception…”

Blow to Modern Errors: Naturalism, Rationalism, Materialism and Anarchism

The proclamation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception was a blow to the modern errors of naturalism, rationalism, materialism and anarchism. Saint Pius X, the last century’s greatest Pontiff, described this blow in his letter commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of that dogmatic definition.

The Pope explains that these errors stem from the denial of Original Sin and the consequent corruption of human nature. The logical result is the denial of the need for a Redeemer. The proclamation of the Immaculate Conception of the Mother of God forces people to admit the existence of Original Sin (from which she was exempt) and all its consequences.2

A First Milestone in the Rise of the Counter-Revolution

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira considered the proclamation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception to be “a first milestone in the rise of the Counter-Revolution.” He writes:

“The new dogma also deeply shocked the essentially egalitarian mentality of the French Revolution, which since 1789 had despotically held sway in the West. To see a mere creature elevated so far above all others, enjoying an inestimable privilege from the very first instance of her conception is something that could not and cannot fail to hurt the children of a Revolution which proclaimed absolute equality among men.”3

He later wrote that the proclamation of the Immaculate Conception was “one of the truly counter-revolutionary acts of Pope Pius IX’s pontificate.”

It was also the first time in the Church’s history that a dogma was proclaimed by a Pope, using the privilege of papal infallibility—even before a council defined it. This counter-revolutionary act challenged the revolutionary claims that placed the council above the Pope.4

American Jesuit historian Fr. John W. O’Malley comments upon this unprecedented act of Pius IX, drawing an interesting conclusion:

“The definition [of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception] was a papal act, pure and simple and in that context a victory for Ultramontanism.”5

The United States and the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception

In 1846, the American Bishops chose the Blessed Virgin Mary, conceived without sin, as the Patroness of the United States of America.

“On Dec. 8, 1854, eight years and four months after the American bishops had chosen Mary Immaculate as the Patroness of the United States, Pope Pius IX solemnly declared the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary to be an article of faith. Numerous petitions for the definition of this doctrine had poured in during the preceding years; and Pope Pius IX had written the encyclical Ubi primum in which he asked the bishops of the world (1) how great the devotion of the faithful was toward the Immaculate Conception and how great their desire for the definition of this doctrine; and (2) what was the opinion and desire of the bishops themselves.

“The American bishops, assembled in the Seventh Provincial Council of Baltimore, May 5-13, 1849, had given a favorable reply to both questions … informing the Holy Father that the faithful in the United States were animated with a great devotion to the Immaculate Conception, and that they the bishops, would be pleased if the Holy Father declared the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception an article of faith.” (see Marion A. Habig, O.F.M., Land of Mary Immaculate, at https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/land-of-mary-immaculate-4089, accessed 9/30/2020, 6:23:58 PM)

On December 8, 1854, when Pope Pius IX read the declaration defining the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, it was the Bishop of Philadelphia, Saint John Neumann, who held the book from which the Pope read. (“St. John Neumann & The Immaculate Conception,” at https://www.americaneedsfatima.org/Saints-Heroes/st-john-neumann.html.)

In a letter to a friend, Saint John Neumann wrote: “I have neither the time nor ability to describe the solemnity. I thank the Lord God that among the many graces He has bestowed on me, He allowed me to see this day in Rome.” (Fr. Michael J. Curley, C.SS.R., Bishop John Neumann C.SS.R.: A Biography [Philadelphia, Penn.: Bishop Neumann Center], p. 239.)

From Gallicanism to Ultramontanism

Exactly ten years later, on December 8, 1864, Pius IX surprised the world with two bombshell documents: the Encyclical Quanta Cura and the Syllabus.6

The publications of Quanta Cura and the Syllabus were badly received by almost all governments of the time because they were dominated by sectarian liberalism. Some, like Napoleon III, even prohibited the bishops from publishing them. The revolutionaries provoked violent incidents in some places. However, there was no lack of gratitude and support for the Roman Pontiff.

French historian Adrien Dansette, after narrating the ecclesiastical resistance in France to the Syllabus concludes: “Pius IX had dealt Catholic liberalism a blow from which it was to take more than twelve years to recover. Meanwhile, the Roman power continued to extend. The great upsurge of pontifical authority, which had already carried the Church in France from Gallicanism to ultramontanism, was soon to take the papacy to the height of prestige represented by the [First] Vatican Council.”7

A Manifestation of the Strength and Vigor of the Church

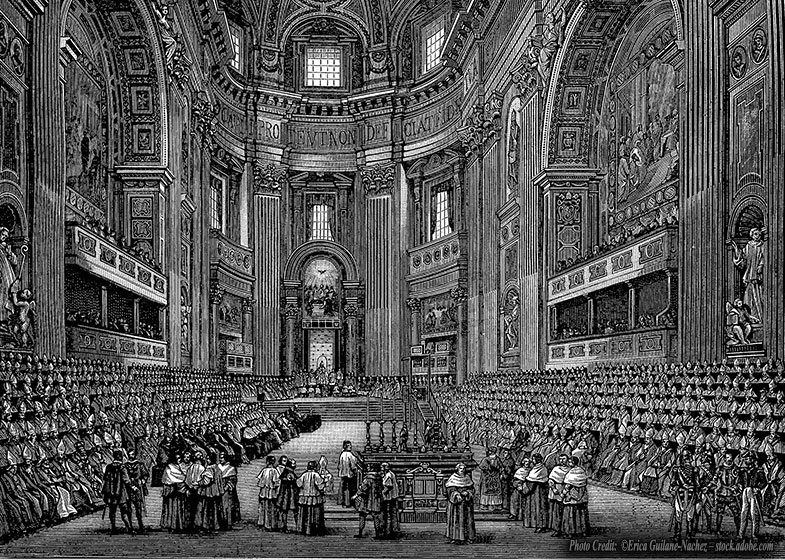

In 1867, Pius IX took advantage of the commemorations of the Eighteenth Centenary of the Martyrdom of the Apostles Peter and Paul to announce his intention to convoke an ecumenical Council. This message was declared before 53 Cardinals, nearly 500 Bishops, ten thousand priests and an incalculable number of faithful from all over the world.

At the end of the centennial festivities on June 29, 1868, he published the Bull Aeterni Patris, designating December 8 of the following year for the opening of the Council and the Vatican Basilica as the site of the assembly.

The Catholic world’s reaction to the announcement was of great joy and enthusiasm: the Holy See, trodden underfoot and politically persecuted, fought even by some of its children, was giving a full test of strength and vigor by issuing a real challenge to its enemies.

The governments of Catholic nations counted on influencing the Council’s decisions. Indeed, since Constantine (fourth century), it had been the custom for Christian princes to participate in the Council, personally or through their ambassadors. To the general surprise and dismay of many, Pius IX did not invite any sovereign or head of state. The Pope made it clear that he wished to solve the internal problems of the Church without any external pressure and that therefore the Council would be exclusively ecclesiastical.

Infallibilists, Anti-infallibilists, “Opportunists”

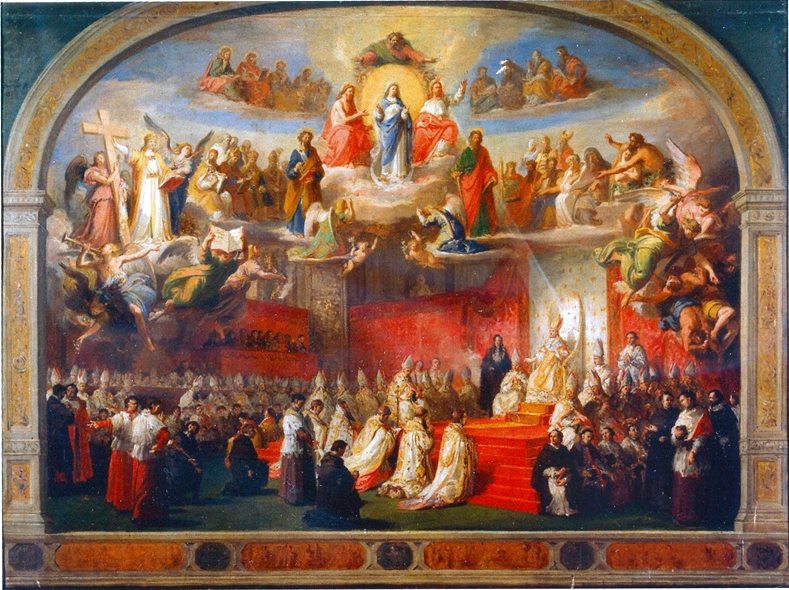

The opening ceremony of the First Vatican Council (the twentieth ecumenical one) was presided over by the Pope and attended by seven hundred Council Fathers and twenty thousand pilgrims. It was solemnly inaugurated in St. Peter’s Basilica on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception in 1869.

The camps were already divided: on the one hand, the pro-infallibility majority, led by Cardinal Manning, Archbishop of Westminster. He had converted from Anglicanism and vowed to do everything to define the Pope’s dogma of infallibility. The cardinal was joined by the bishops of Italy, Spain, England, Ireland and Latin America. The minority camp consisted of anti-infallibilists and “opportunists.” The latter were ironically called opportunists because they considered the definition of the Pope’s infallibility “inopportune.” Most saw this excuse as a skillful formula to fight the dogma without clashing head-on with Catholic doctrine. The minority opposition included the German bishops, almost the entire episcopate of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and a third of the French bishops.

Photo Credit: ©Erica Guilane-Nachez – stock.adobe.com

As the European political situation deteriorated daily, there was the risk that a war might interrupt the Council’s activities. Thus, 480 bishops of the majority addressed a Postulatum to the Holy Father, asking that the scheme on pontifical infallibility be immediately discussed, leaving the other issues on the agenda for later consideration.

“I Felt Such Indignation That the Blood Went to my Head…”

After the Pope accepted the request, the Council Fathers began to discuss the draft Constitution De Ecclesia Christi, focusing on chapter XI, on the Primacy of the Roman Pontiff, which included the definition of infallibility.

The debates were heated, and the minority provoked many incidents. An anti-infallibility bishop took his attacks on the prerogatives of the Roman Pontiff so far that the Cardinal-President of the assembly had to interrupt him, sounding his handbell vigorously. Indignant protests were heard in the plenary.

Saint Anthony Mary Claret, former Archbishop of Santiago de Cuba, even had a minor stroke, as he recounts:

“Since, on this matter [papal infallibility], I cannot compromise for anything, or with anyone, and I am willing to shed my blood, as I said openly in the Council when hearing the nonsense and even blasphemies and heresies that were said, I felt such an indignation and zeal that the blood rose to my head and produced a cerebral affection.”8

After heated debate, the arguments against infallibility were refuted one by one. The bishops of the opposition minority decided to abstain from voting, withdrawing from Rome the day before the vote.

Amid Lightning and Thunder, Like Moses at Sinai

On July 18, 1870, the solemn promulgation of the pontifical dogma of infallibility took place. After the Mass of the Holy Ghost, the enthronement of the Gospels, and the singing of the Litany of Saints, the Pope blessed the Council six times.

The Secretary announced that a restricted session was to begin. As he was about to order the faithful to leave, the Pope ordered that they be allowed to attend the voting and proclamation.

After the solemn reading of the Constitution, Pastor Aeternus, the Secretary addressed the Council Fathers:

“Most Reverend Fathers: Do you approve the decrees and canons contained in this Constitution?”

The same Secretary communicated to the Pope the result of the vote:

“Most Holy Father: All but two have approved the canons and decrees.”

Pius IX then stood up, replaced the miter and with great calm and majesty, pronounced the words:

“The decrees and canons contained in the Constitution that has just been read pleased all but two Fathers. We too, with the approval of the Holy Council, as they were read,

DEFINE THEM AND WITH APOSTOLIC AUTHORITY CONFIRM THEM.”

“Long live Pius IX! Long live the infallible Pope!” were the cries of joy that echoed through the vaults of St. Peter.

During the whole ceremony, one of the most violent storms in the memory of the Eternal City raged. Amid lightning and thunder—as in Sinai, when the Lord gave Moses His Law—the pontifical infallibility was proclaimed. At the Pope’s last words, the atmosphere calmed down and, suddenly, a ray of sunshine swept through the dark clouds, illuminated the Pontiff’s venerable and majestic countenance, then lighted the whole room.

* * *

The next day, France declared war on Prussia. The French and German bishops rushed to their dioceses. The general concern caused by the war cut short the Council.

In those countries dominated by sectarian liberalism, the definition of papal infallibility provoked a religious persecution against Catholics. In Germany, this clash was adorned with the sound (and fallacious) name of Kulturkampf (German: “culture conflict”).

Sustained and encouraged by the Pontiff, both pastors and faithful reacted magnificently to the attacks. The persecutions served to bind Catholics together and increase their loyalty to the Chair of Peter.

A Great Sacrilege

The war caused France to withdraw its small garrison protecting Rome, leaving the city at the mercy of the House of Savoy.

Pius IX maintained his habitual—and supernatural—tranquility throughout the new crisis. He dealt with ecclesiastical matters as if the most fierce struggles were not being prepared around him. On September 19, the twenty-fourth anniversary of the events of La Sallete, he signed the decree recognizing the apparitions of the Virgin of Tears. At five o’clock in the afternoon, he went to the Scala Santa and climbed up them on his knees, begging God that, by the infinite merits of the Most Precious Blood of Jesus Christ, shed on those steps, have mercy on His Church.

Meanwhile, Piedmontese troops, commanded by General Raffaele Cadorna, reached the Aurelian Walls and placed the Eternal City under siege. The papal force, commanded by General Hermann Kanzler, totaled 13,157 men facing more than 50,000.

After a terrible cannonade, which lasted five and a half hours, the Pope’s heroic defenders were ordered to suspend the combat. Pius IX, seeing that he could not face the assault, had determined that the resistance should last just long enough to make it clear in the eyes of the world that the Vicar of Christ yielded only to violence.

On September 20, after a three-hour cannonade breached the Aurelian Walls (Breccia di Porta Pia), the Piedmontese infantry group of the Bersaglieri entered Rome.

The Pope was thus sacrilegiously stripped of what remained of his territorial sovereignty. From then on, the Roman Pontiff considered himself a prisoner in the Vatican until the Lateran Treaty in 1929, which created the Vatican City State.

Hatred of the Wicked, Title of Glory

Pius IX died on February 7, 1878, at 86. He had ruled the Church for thirty-one years, seven months and twenty-two days. He was the first Pope to surpass the traditional “twenty-five years” of the Prince of the Apostles, and to whom the aphorism was not applied: “Non videbis annos Petri”—“You shall not see the years of Peter.”

His death filled the whole Catholic world with consternation. Catholics everywhere paid him the homage due to a great Pope. Undoubtedly, Pius IX was one of the greatest Pontiffs in the history of the Church. He used exceptional energy to defend the rights of the Church and the Apostolic See. He committed himself with unreserved devotion to make them triumph. He knew how to magnify the influence of the Papacy in the eyes of his contemporaries. The Papacy obtained a prestige and authority known perhaps only to the great medieval Pontiffs.

That is why he was so loved and venerated by the faithful. And also why he was so hated and persecuted by the enemies of the Church and Roman See. This latter is one of his greatest titles of glory.

Updated October 21, 2020.

Footnotes

- In his well-documented biography of the great Pope, Italian historian Roberto de Mattei discusses “the myth of the ‘liberal Pope.’” Cf. Pius IX, (Herefordshire, England: Gracewing, 2004), 12-16. See also Daniel-Rops, The Church in an Age of Revolution (1789-1870) (Garden City, N.Y.: Image Books, 1967), 15-18; E. E. Hales, Pio Nono: A Study in European Politics and Religion in the Nineteenth Century (Garden City, N.Y.: Image Books, 1954), 18-43; Adrien Dansette, Religious History of Modern France (New York, N.Y.: Herder and Herder New York, 1961), v. I, 247-51.

- Saint Pius X, Encyclical Ad Diem Illum, February 2, 1904, n. 22, available at http://www.vatican.va/content/pius-x/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-x_enc_02021904_ad-diem-illum-laetissimum.html.

- Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, “A First Milestone in the Rise of the Counter-Revolution,” at https://tfp.org/a-first-milestone-in-the-rise-of-the-counter-revolution/.

- Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, “Three Reasons the Church’s Enemies Hate the Immaculate Conception,” at https://tfp.org/three-reasons-the-churchs-enemies-hate-the-immaculate-conception/.

- Cf. John W. O’Malley, Vatican I: The Council and the Making of the Ultramontane Church (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2018), p. 103.

- W. F. Hogan, “Syllabus of Errors,” New Catholic Encyclopedia, at https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/syllabus-errors.

- Adrien Dansette, op. ci., v. I, 300.

- Saint Anthony Mary Claret, letter of July 1, 1870, to Father José Xifré, in San Antonio Maria Claret / Escritos autobiográficos y espirituales, (BAC: Madrid, 1959), p. 924.