In the previous article, we observed the hat as a symbol of dignity; we will now analyze it as an expression of good manners and how its use decayed before it disappeared

“Who’s that lady with the hat?” a friend asked during a Requiem Mass celebrated at the Paulaner Kirche, in downtown Vienna. She was the assistant to a deceased professor.

assistant to a deceased professor.

Her black hat, surrounded with a purple ribbon, emphasized her sorrow for her lost master. Its wide brim delicately shaded her face, separating her from the ambiance so she could better recollect in her grief. At that religious ceremony, she seemed to radiate an aura of suffering and people’s grieving gazes concentrated on that aura of mourning.

With the growing equality between the sexes — the so-called “liberation” of women — hats have been withdrawn from feminine countenances. This is one of the many things lost in modern times, as hats brought out feminine dignity by supporting a ladies’ delicate nature.

In a natural and irresistible way, the hat calls a certain attention even before one is able to make an aesthetic or moral judgment of it. Yes, in a natural way, because it sits right above the face, the part of the body – if not the most visible – certainly the one which people most try to see.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Nothing in a person attracts one’s gaze more than a countenance; through which if one knows a person; one’s traits form a visage which reveals one’s mentality and state of mind. A person’s face demands respect and should only be touched with care, if not reverence. While shading it, the hat places itself at the center of people’s gazes, modifying one’s countenance, manifesting a state of mind, accentuating a person’s mentality and defining their character. As a piece of practical apparel the hat was designed to provide shade, but in fact, it sheds much light on one’s personal qualities!

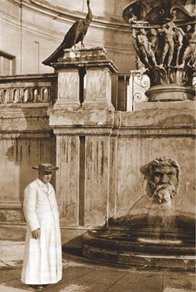

Let us take for example the classical ecclesiastical hat. In the simplicity of its form and the uniformity of its black color, it radiates the seriousness of the religious state which inspires reverence. Saint Pius X wore one with his white cassock, and in his unpretentious simplicity, it accentuated the supernatural expression of the immense dignity of the world’s highest-ranking Hierarch, the Pope [see photo at right]. Yet the modest black hat worn by a humble village parish priest also “leads to discern, through the sensible appearance, something which of itself is not sensible but spiritual” because God is represented here. (Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira)

Humility Is Compatible with the Rich Dress of One’s Office

The judgment of the aesthetic and moral representation of a hat is chosen by the person who wears it. Is it modest, unpretentious or in poor taste? Each type of hat has its own character that is derived from its shape, size, material, color and ornamentation, therefore, the character of the hat is most telling of the character of the person wearing it. Styles vary according to the circumstances of civil life. Over many centuries daily requirements, feasts, gala and funeral occasions gave rise to the appearance of a huge variety of styles that expressed, from the moral standpoint, the image that ladies and men wanted to give of themselves in the ambiences that they frequented. The hat’s style expressed a person’s profession, prestige and social condition in a reasonably accurate manner.![]()

FREE e-Book: A Spanish Mystic in Quito

From the seventeenth century foward, hat styles began to reflect less of the origin and dignity of those wearing it and much more the socio-politico concept in society dictated by fashion.

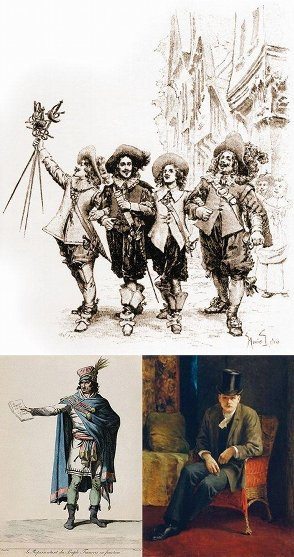

Let us exemplify this with a large-brimmed hat topped by a feather [see photo of Musketeers], like the model worn by the Three Musketeers and other dignitaries of the Ancien Régime. The brim suggests protection and generosity; the feather, lightly rising above with elegant movements, brought to mind the mobility of thought and the transcendental ideals proper to the chivalry of the time. The tone of a conversation among gentlemen could be noticed through the movement of the feathers, first oscillating and nervous, then immobile and, as it were, pensive.

the Ancien Régime. The brim suggests protection and generosity; the feather, lightly rising above with elegant movements, brought to mind the mobility of thought and the transcendental ideals proper to the chivalry of the time. The tone of a conversation among gentlemen could be noticed through the movement of the feathers, first oscillating and nervous, then immobile and, as it were, pensive.

When ladies would present themselves, men would remove their hats with their plumes in a harmonious winding movement that gave a note and measure of courtesy in accordance with the lady’s social standing. The hat was one of the elements one used to express good manners.

Social norms determined the circumstances and ways to remove or tip one’s hat in society, hence, honoring each one according to their place in life.

The French Revolution adopted styles suitable to the egalitarian and utilitarian philosophy of the Enlightenment. Its style [lower left photo] contained a renunciation of splendor.

It embodied a brutal rupture with the past. The absence of a brim made patent the confinement of ideas and revolt against centuries-old rules of good taste. Instead of plumes, a bunch of cereals stalks symbolized the primacy of the practical over the marvelous and ideal. Under the influence of such symbols, egalitarian heads bubbled with hellish effervescence while sending the heads of others to the scaffold, causing many revolutionaries, as undaunted and inelegant as the straw on their hats, to later roll relentlessly under the cold blade of the guillotine.

During the French Revolution there appeared the first hats with a high crown and reduced flaps [lower right photo]. They were inspired by the “people,” in whose name the Revolution was made and these were the forerunners of the top hat that dominated men’s fashion in the nineteenth century. In France, the douceur de vivre had come to an end, and the common black top hat and suit accurately expressed that sadness. Although the politicians, ambassadors, nobles and industrialists who wore it gave the somber appearance of undertakers, the top hat still retained some elegance and gravity.

Modesty of Dress and the Love of God: An Effective Way to Defend the Family

Its raised crown required solemn and measured movements. Its majestic height and silky reflections almost replaced the light movements of the plumes of yesteryear but flexibility was no longer present as it was replaced by a tall stiff cylinder. From the beautiful plume that moved with grace to the black stiff cylinder, the world switched from the elegance of the ancien regime to the practical, geometric objectivity of the industrial century.

Men gave up top hats and women their beautiful hats almost entirely. “They’re useless,” “old fashioned,” “have no place in modern life,” is the recurrent mantra one hears when talking about hats. On behalf of functionality, one hardly even notices the loss of dignity brought about by the disappearance of hats. One can only ask if people’s heads have become emptier as a result of the black cylinder into which it has been inserted.