In today’s polarized climate, Americans are being asked to choose between “either globalism or nationalism.” It is a false dilemma since neither side represents the balanced position found in an authentic patriotism that first appeared in ancient times.

However, even ancient forms of patriotism, while sound in their origin, could not keep this balance. They succumbed to unsound forms of the “nationalism” or “imperialism” of their time. They did not have the strength of Christian patriotism, watered as it was by the Blood of Our Lord and Savior.

Thus, a look at what went wrong in ancient patriotism might help avoid problems with the present search for authentic expressions of this most needed virtue.

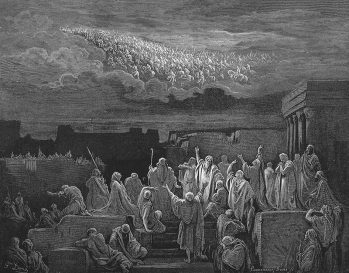

Israel’s Strong Sense of Patriotism

The first example is Israel. The Bible teaches that God called Abraham and formed a Chosen People out of his descendants. The Jews had to fight mightily to preserve their religious identity since pagan populations adoring false gods surrounded them.

In this fight to remain faithful to Jehovah, they developed a strong sense of patriotism. The hardships of their sojourn in Egypt increased these sentiments. This patriotism was further bolstered when Samuel, the last “judge” of the previous tribal system, wielded the universal and absolute power of a monarch. Later, David represented the height of this patriotic ideal as the builder of the Temple of the one true God in Jerusalem, the sacred city he had chosen for his capital.

Salomon’s infidelities, however, led to the creation of the separate Kingdom of Israel in the north, while the Kingdom of Juda occupied the territories of the south, around Jerusalem. The fall of Jerusalem in 586 BC and the Babylonian captivity were deathly blows to the people of Israel.

10 Razones Por las Cuales el “Matrimonio” Homosexual es Dañino y tiene que Ser Desaprobado

After fifty years of exile, the Jews returned to Palestine and reconstructed the Temple. The prophets of the time, Zachary and Malachy, tried to secure the people’s fidelity to God’s law and worship in the face of new threats.

The Fall of Israel Into Two Extremes

Despite the prophets’ efforts, some Jews fell into the trap of the “globalism” of that time represented by the Hellenism that Alexander the Great’s victorious armies popularized all over his empire. The Jewish high-priests, supporters of the Sadducees, even adopted Greek names and introduced Hellenic practices into the society of the Holy City. Others, who followed the Pharisees, adopted what might be called a jingoist “nationalism” of the time. These partisans expressed the hope for a worldly Messiah who would recover Israel’s independence, and make it the ruler of the world.

The real patriotism was represented by the priestly family of the Maccabees, who placed the glory of God above everything else. However, around 63 BC, the Romans invaded and put an end to the last Jewish dynasty, which was also a victim of the division between the globalist Sadducees and the nationalist Pharisees.

The Breakthrough of the Greeks…and Their Limitations

How did Hellenism contribute to the fall of Israel? History records how, in Classical times, all tribes defended themselves and advanced their interests out of a mere gregarious impulse of living together in community. The Greeks had the great merit of breaking out of these small uncultured groupings. They gave their allegiance to their great cities, like Athens or Sparta. In so doing, they advanced a higher good that could be found it the promotion of civilizational values like order, good government, individual freedom, art and the refinements of life.

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

However, these great, highly civilized cities became victims of a narrow-minded isolationism resulting from their pagan religion. Contrary to the general view that geography prevented Greek cities from uniting into a single state, historian Fustel de Coulange writes that their religion of ancestor worship had the effect “over a period of centuries, of rendering impossible the establishment of a social form other than that of the city.” Indeed, “each city, through the exigencies of its religion, had to be absolutely independent,” Each had its law, sovereign justice, calendar, currency, weights and measures. “No one believed that there should be anything in common between two cities.”

Between two neighboring cities, “there was, therefore, something more impassable than a mountain: it was a series of sacred obstacles, the differences of cults, the barrier each city erected between strangers and its gods.” Between two cities, there may be an alliance, but never a complete union, “for religion made of each city a unit which could not join any other. Isolation was the law of the city.”1

Alexander’s Vision

Only someone like the Macedonian leader Alexander the Great could conceive and execute a pan-Hellenic project that created a vast empire stretching from the Adriatic Sea to the Indus River. However, even this empire lost its soul on its way to universal dominion.

The vastness of the empire favored religious syncretism (like Greco-Buddhism) as an attempt to homogenize the populations of Asia and Europe. The resulting hybrid Hellenistic civilization “orientalized” Alexander’s Western states.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

After his death, three powerful dynasties divided his empire and ruled over a vast cosmopolitan trade zone through professional bureaucrats. This soulless, decadent Hellenistic world eventually fell to the Romans in stages. The final blow was when Octavian defeated Mark Antony, Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt, in 31 BC. Octavian took the name Augustus and became the first Roman Emperor.

Roman Patriotism and its Empire

This conquering Rome gave birth to the word patriot, a derivation of pater and patria, (meaning father and fatherland). This concept expressed what the Romans called mos maiorum (ways of the fathers) and contributed to the glory of the city.

“From their pioneer forefathers, Romans inherited respect for strength and discipline, for loyalty, industry, frugality and tenacity (…) The Roman owed his loyalties to the gods, the state and the family. Where the earlier Greeks had cherished their individuality, the Roman always subordinated his personality to greater forces,” writes Moses Hadas.2

This subordination favored the expansion of the small city-state of Rome into a vast Empire, because Rome “was from the outset anxious to extend her political control, first over all of Latium, then over all of Italy, and eventually over the whole Mediterranean basin.”3

Nationalism and Patriotism

Unconcerned by the metaphysical ponderings so prized by the Greeks, the practical Romans “adopted the imperial idea, which appealed to their lust of power.”4 They transformed this idea into a reality by the strength of the Roman legions, which brought prosperity and happiness in their wake. The famous pax romana brought the flourishing of city life in old quarters but also the improvement of new towns around legionary camps or in response to the needs of expanding commerce.

Rome’s Achilles’ Heel

However, this expansive imperialism had an Achilles’ heel: “A pleasant intercommunion … of nationality, language and color, spread from one end of the Empire to the other. In the service of Rome, Syrians and Spaniards, Africans and Britons mingled together without difficulty or wounding discrimination. A wide and indulgent tolerance was the mark of the age. (…) Of religion as such there was no persecution, for the Roman Pantheon was hospitable to every god.”5

Indeed, the continual flux of divinities—some gods melted away while others arrived—resulted in a skeptical attitude toward religion manifested by Stoics and Epicurean philosophers. Later, the masses were attracted by Bacchanalian religions that veterans of Eastern campaigns brought back with them.

“Of the ultimate fate of the Empire there were as yet no apprehensions. It was the universal and comforting belief that Roman rule would endure forever,” says British author and parliamentarian Herbert Fisher.

Science Confirms: Angels Took the House of Our Lady of Nazareth to Loreto

However, that security was shaken by other trends: “Already in the time of Augustus grave anxiety was felt as to the failing birth-rate of Italy. Legislation was attempted, but while the natality of Jews, Egyptians and Germans steadily advanced, the Italian birth-rate continued to fall. The wastage of almost incessant warfare [mostly occasioned by intestine civil wars] the practice of infanticide, the growth of luxury and self-indulgency (…) were among the causes which contributed to the depletion of the manpower in the two leading countries in the Mediterranean. By the age of Marcus Aurelius, there was little left of the virile population of the ancient Greece or of the best breeding stocks of Rome and Italy. (…) A policy was then for the first time initiated of directly opening the Empire to colonization. Blocks of barbarian warriors were invited to settle on the waste places behind the Roman frontiers. Once inaugurated, the process of infiltration continued.”6 The rest of the story is found in Rome’s fall.

The vigor of patriotism of the early ages had built a magnificent Empire. However, it was the victim of its own imperialism because it was interiorly corrupted by Rome’s religious relativism and the resulting skepticism expressed in Pontius Pilate’s question to Jesus: Quid est veritas?

The Ancients did not have the perfect balance between the love of God and country. They could not reach the equilibrium needed for a legitimate love of the fatherland and the orderly love for all mankind. This balance only reached its historical plenitude in Christendom during the Middle Ages, as a fruit of the Catholic faith.

Footnotes

- Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, The Ancient City, in Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, Nobility and Analogous Traditional Elites in the Allocutions of Pius XII, p. 500-501.

- Moses Hadas, Imperial Rome (Time-Life Books, 1965), p. 12.

- Oscar Halecki, The Millenium of Europe (University of Notre Dame Press, 1963), p. 7.

- Ibid. 8.

- Herbert A. L. Fisher, A History of Europe, (Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1935), p. 91.

- Ibid. 91-92.