Speaking with a friend recently, we chanced to talk about money and coins. He is a coin collector and had just visited a coin shop nearby. I mentioned my own studies of medieval economy and its coinage. Much to my surprise and delight, he reached into his inner coat pocket and pulled out a gros tournois coin minted almost 750 years ago in France.

Speaking with a friend recently, we chanced to talk about money and coins. He is a coin collector and had just visited a coin shop nearby. I mentioned my own studies of medieval economy and its coinage. Much to my surprise and delight, he reached into his inner coat pocket and pulled out a gros tournois coin minted almost 750 years ago in France.

For me it was something of an emotional experience. I had seen pictures of the coin and knew a bit of its history. But I had never actually held the coin in my hand. When my friend handed it to me, I was thrilled by the chance to “touch history.”

The Origin of the Coin

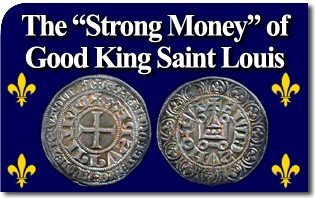

This is no ordinary coin. It is small, slightly larger yet much thinner than a dime. It is also beautiful with inscriptions and symbols full of meaning upon its faces.

It should be explained that this coin was born of prosperity, since the value of the then-standard denier, or penny, was inconveniently small for use in trade and commerce. Introduced in 1266, this medieval silver coin, worth 12 denier, provided the added value needed to favor France’s expanding economy.

It was called the gros tournois because it was minted at the city of Tours — the towers of the city’s abbey appear on one of the coin’s faces. While many cities in medieval France minted their own gros coins, the ones from Tours were among the most stable over the course of centuries.

An Extraordinary Ruler

However, what makes this particular coin very special is the fact that he who minted it was no ordinary person. His name actually appears in Latin on the coin and reads: Ludovicus Rex, or Louis the King, also known as Saint Louis.

King Saint Louis IX (1214-1270) was a virtuous ruler beloved by his people and known for his passion for justice and his love of the poor. He became legendary in history for delivering fair judgments to all, rich and poor, who came before him under the tall oak tree of Vincennes.

Good and saintly kings are not only the stuff of legends, but they are also excellent economists. Under his reign, France grew and prospered.

As I held his gros tournois in my hand, I could not help but think that we would do well to implement the monetary policies contained in that coin.

A Return to Sound Money

We would do well to return to sound money. The gros tournois was sound money. It was ample in supply, stable in value, beautiful in appearance.

More importantly, the coin did not fulfill the functions, so common in our days, of facilitating unbridled credit, frenzied expansion, and speculation. Indeed, such practices were discouraged by the moral codes of the time. The gros tournois fulfilled the primary and true functions of money, which should serve as a measure of value, a stable exchange medium, and a temperate store of wealth. In addition, this money did not originate from or thrive upon debt.

The gros tournois was a practical and adaptable currency. It was conceived to facilitate the convenience of exchange with common sense, wisdom and flexibility. It did not dominate over other alternative local currencies. It enjoyed the trust of the people, and could be considered a true expression of the culture.

From a purely technical standpoint, the coin represented sound money as defined by many modern economists.

A Return to Moral Money

However, it is not enough to have just sound money if we are to return to order. We would do well to return to moral money.

Saint Louis did not succumb to the temptation of implementing monetary policy based solely on the mechanical manipulations of formulae and numbers. He did not inflate or debase his currency to fit with personal goals.

Modern economists blind themselves to the obvious fact, so often verified, that in the stormy history of money, bad money most often appears because of the despotic acts of men and rulers. Their good or bad actions really determine the course of the economy and the soundness of money.

The gros tournois was sound because Saint Louis sought after justice. His money enjoyed the trust and confidence of the people because they knew the saintly king would not manipulate or debase it. He used the power and prestige of his office to advance the common good and not his personal affairs.

Money fails when injustice rules and the rule of law is ignored. Then, there is no monetary system that cannot be circumvented or perverted. In vain do we speak about a sound monetary policy outside of virtue. Indeed, virtue is the best backing of money; it far outshines the brilliance of gold.

“Saint Louis IX mediating between King England and his Barons” by Georges Rouget.

A Return to Godly Money

Finally, we would do well to return to what might be called “Godly” money. Such an affirmation might irritate secular people who wish to see God banished from all worldly affairs.

The gros tournois was Godly money. Upon one of its faces, there is a large cross of Christ. The abbreviated inscription on the front says in Latin: benedictum sit nomen domini nostri Jesu Christi or “blessed be the name of Our Lord Jesus Christ.”

It is proper that even money should call to mind God and our last ends. Meditating on our salvation puts our desires and appetites in order, which in turn tempers the frenzied excesses of unrestraint in an economy. The cross on the coin signifies the fact that money cannot take away the suffering and trials of our fallen nature. It cannot buy happiness.

During that age of Faith, it was not unreasonable to think that when the name of Jesus Christ is blessed upon coinage, Christ’s blessings upon the economy can be expected, as indeed happened in Saint Louis’s times.

Statue of King Saint Louis IX of France holding the Crown of Thorns, Basilique du Sacré-Coeur, Paris, France.

Confiding in Government

Alas, in our age of disbelief, people today prefer to put their faith in the Federal Reserve and central banks — from which no blessings flow. Rather than throw themselves upon their knees, people prefer to throw themselves into the frenetic intemperance of modern markets that encourage instant gratification and unbridled indulgence.

And when frenzied economies fail, as they inevitably do, they call upon massive governments to prop them up, incur debt, and destroy yet further the currencies of the land.

Would that we might return to the wise policies of Saint Louis! History records that when money suffered debasement from wars and unsound policies in fourteenth-century France, the people clamored and longed for the “strong money” of good King Saint Louis.

Holding the gros tournois in my hand, I found myself clamoring for the strong money of Good King Saint Louis. It is still strong.

As published in Crisis Magazine.