The Ecological Turn of “Postmodernity”

When compared to yesterday’s culture a few decades ago, today’s “postmodern” culture has some rather surprising differences. One such difference is its ecologist tendency to rediscover, re-evaluate and propose models that are backward, primitive, wild and tribal.

In yesterday’s culture, man was acclaimed as the master of Nature. Today, everyone revers Nature as the idol and mistress of humanity and its destiny.

Rationalism and the rule of science dominated yesterday’s culture that sought to shape an advanced civilization and build a bureaucratic and technocratic society. Today, the postmodern trend is toward an irrational and mystical culture, aimed at forming a regressive civilization.

Yesterday, the plan was a cultured, stable, wealthy, comfortable and prosperous society. Today, however, the postmodern model shapes an ignorant, precarious, miserable, uncomfortable and stripped-down society. The “deconstruction” of society is transformed into an anarchic and tribal community.

This “return-to-nature” trend is not as new as it seems. Looking over the history of the Revolutionary process—under the guise of building a future designed on the basis of scientific and technological rationality—there often appears dreams of a return to a utopic and lost past, an unspoiled beginning, an “earthly paradise” in which humanity would live happily, unmindful and free of all concerns.

The Discovery of a Tribal Model of Society

History is full of failed utopian projects seeking to recover a lost happiness found in an unspoiled beginning. Their number exploded in the sixteenth century coinciding with the advent of “modern civilization.” These experiments tried to put knowledge and willpower at the service of a Utopia that would build a free and happy society.

Shortly after the discovery of the Americas, the ships began to bring not only priests, geographers, naturalists and traders, but also “philosophers” to the world. Today these latter would be called ethnologists or anthropologists. They were eager to study the lives of the discovered peoples.

10 Razones Por las Cuales el “Matrimonio” Homosexual es Dañino y tiene que Ser Desaprobado

Those scholars were disappointed with their own civilization, which they accused of being complicated, artificial, unjust and torn by divisions and wars. The Protestant revolution had just broken out. In their journeys to the New World, they sought to rediscover an “earthly paradise,” an alternative and new model of society to replace old Europe. Using today’s trendy terms, they abandoned the “center” to search for the “suburbs.” They refused exclusivity and embraced “opening up to the other.” They rejected the established uniformity to discover diversity.

Thus, some scholars did not merely study the lives of the savages objectively but interpreted them according to their own criteria. They naively believed that tribal society had no property, trade, families, institutions, laws, privileges, hierarchy, political or religious authorities. They believed that the savages lived free from certainties, desires, scruples, insecurity, aggressions and wars. They lived a carefree and unstructured life that today might be characterized as Buddhist or vegan (although the savages avidly ate animals).

According to those scholars, all these things that the savages lacked made them not only ignorant and naïve but also peaceful, chaste, humble, altruistic, generous and wise. They did not suffer the effects of Original Sin, because they enjoyed an original innocence. Thus, the scholars imagined they had discovered in tribal society the ideal community they dreamed of. They elevated tribal life as a model that they proposed to Europeans as an alternative to their corrupt civilization.

The Uncivilized Utopias of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment

The sixteenth century was a historical period that marked the triumph of humanism, neopagan civilization and secularized society. It also saw the rise of utopias that claimed to gather together the knowledge and power needed to return to an “earthly paradise.”

Some Protestant movements of the time such as the Anabaptists already dreamed of a society not only without the Papacy but also without any religious authority, political power, family or private property.

Some proponents of the so-called cultured Renaissance were skeptical about religion, libertarian in politics and libertine in morality. They dreamed of a society that was happy because it was free from religious, political and juridical constraints. For example, the Frenchman Etienne de la Boétie, a pupil of Montaigne, hoped that Europe would become a continent “without Faith, Kings or Laws.”

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

Between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, illustrious humanists elaborated more precise utopian projects. It began with (Saint) Thomas More, who, with his famous book, Utopia (1516), launched the concept with the title of the book. Later, Dominican Tommaso Campanella wrote The City of the Sun (1602). However, those literary fantasies were not meant to be imposed on real society.

Later, however, the Anglican Sir Francis Bacon with his New Atlantis (1612), and the Puritan Gerard Winstanley with his Law of Freedom in a Platform (1652) proposed Utopias as ideal programs that could be scientifically implemented by employing political and economic techniques invented by the then-nascent “social sciences.”

To avoid ecclesiastical censorship, many authors proposed their ideal societies by writing literary fiction stories of the geographic discovery of distant societies. In his book on a fanciful voyage to The Southern Land (1676), Gabriel Foigny imagined a primitive society composed of multi-sexed asexual individuals with ambiguous or mutant sexuality, not unlike the imaginings of today’s gender theorists.

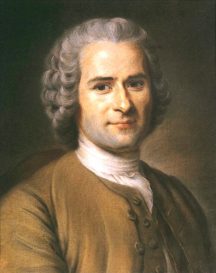

Although society of the Enlightenment was supposedly cultured, scientific, pragmatic and refined, this tribalist utopian literature displaying contrary characteristics continued during the eighteenth century. Writers such as Fontenelle, Meslier, Deschamps and Rétif de la Bretonne argued that happiness comes from “simplicity,” understood as the rejection of dogmas, laws, duties, obligations and social constraints. Morelly drew up his The Code of Nature (1755), Rousseau developed the pedagogy of “wild spontaneity,” and Diderot proposed a political program that revolutionaries tried to implement during the French Revolution with the disastrous results that are well known.

The Tribal Utopia of Socialism

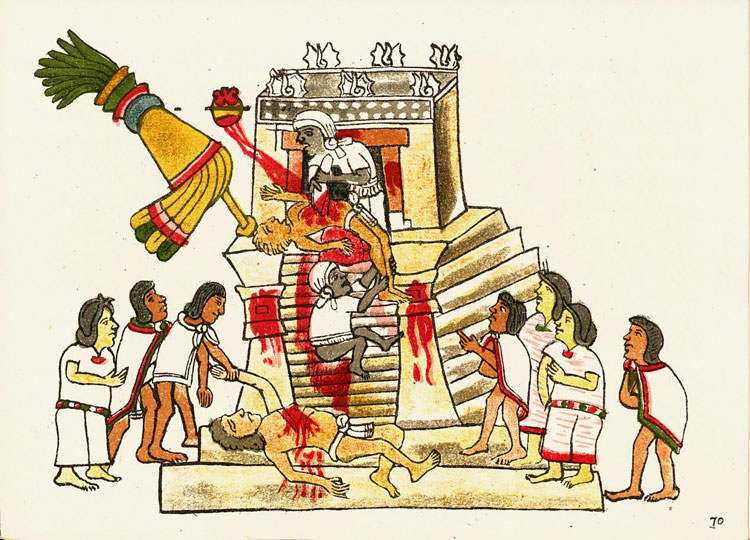

In the nineteenth century, some political scientists and sociologists joined the ethnologists and anthropologists who were studying the social system of the pre-Columbian Amerindian societies (Aztecs and Incas). Although those societies were tyrannical, oppressive, slave-makers and even perpetrators of massacres, these scholars praised them as based on “solidarity,” i.e., living in sync with nature. They marveled at how these societies could merge countless individuals into collective entities so that each acted as one compact and powerful body, like that of a “big animal.”

Some socialist authors sought to counter the technocratic model of positivism with the primitive model of the “Third World” or the tribal life of savage communities. They dreamed of a society liberated from religious, political and economic authority. Everything was collectivized: marriage, the education of offspring, property, inheritance, work, entertainment, teaching, housing, food and clothing. This ideal called for the socialization of birth, growth and death, which presupposes secularization and impoverishment. For example, the utopian socialist Fourier designed a social system like that of the Amerindian empires, in which every aspect of individual life was subjected to a tribal-type collectivism.

This primitive model also seduced so-called scientific socialism. Marx programmed his communist revolution to abolish alienating and oppressive factors—property, money, commerce, family, education, law, political and religious authorities—that dominated history from patriarchal to bourgeois society. This abolition would allow a return to an ideal primordial community. This “primitive horde” imagined by Engels, was a community, in which “everything is in everyone,” and all are equal, not only in possessions and power but also in their thoughts, desires and feelings.

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

The early experiments by the Leninist regime in Russia and the Maoist one in China had this goal. The bloody dictatorship of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia was a tragic, if obviously failed attempt, to eradicate an entire population from its civilization by sending its people into the forests to experience a savage tribal life.

“Postmodern” socialism began with the sexual and ecological revolution elaborated by Reich, Fromm and Marcuse. Since 1968, the postmodern program consists of pursuing the original equality yet farther by promoting an irrational, stripped-down and destructive dimension.

That being the case, it is no wonder that the very term “Revolution” (from the Latin revolvere) does not express an advance towards the future but a return to the past, to a lost and lamented primordial state of perfection and happiness imagined as a “reign of freedom and equality”—when people give up civilization. Thus, the real choice facing the world today is between revolutionary barbarism and Christian civilization.

More articles like this may be found on Pan-Amazon Synod Watch, at https://panamazonsynodwatch.com/.