War hero, practicing Catholic and cherished friend of the American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property (TFP), Col. John Ripley, died at his home in Annapolis, Maryland on November 1, 2008.

War hero, practicing Catholic and cherished friend of the American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property (TFP), Col. John Ripley, died at his home in Annapolis, Maryland on November 1, 2008.

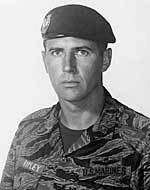

Col. John Ripley was born June 29, 1939 in Radford, Va., and descended from a line of soldiers that dated back as far as the Revolutionary War. After graduating from high school he chose to continue that military tradition by joining the Marines at 17 years of age. He described his father as being “keen on the idea” while his mother wept. Shortly after joining the Marine Corps, he applied for an appointment to the United States Naval Academy. He was ultimately accepted to this prestigious institution and graduated in 1962.

Quad Body

In 1966, he was sent to Vietnam as the commanding officer of Lima Company, 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines and received what he referred to as a baptism of fire. It was an incredibly hostile environment, he said, in which the daily exposure to intense conflict took the lives of many of his fellow Marines. He himself was wounded in action but would return in 1967 to finish his tour of duty.

Upon completion of his first tour, Col. Ripley attended Amphibious Warfare School and then went on to train with the British Royal Marines where he completed the organization’s demanding commando course. He would later complete the equally grueling programs of the Army Rangers, Marine reconnaissance and Army Airborne. In doing so he earned for himself the designation of Quad Body which is a unique distinction among American fighting men who have completed the world’s toughest military training programs.

“In our training,” he would say about the Ranger program, “we were kept in a constantly deprived state, sleep deprivation all the time, and even [deprivation of] food. They did that purposely, and it had a very good effect, because you learned you could operate under these conditions when your body was weak and your mind was addled.”

One of the last tributes he received was to be inducted into the Army Ranger Hall of Fame. He is the only Marine to have received such an honor.

Dong Ha Bridge

In 1971, he would return to Vietnam and the Ranger training he received would serve him well in accomplishing a task that would ultimately be a defining point in his life. It occurred in March 1972 during what has come to be known as the Easter Offensive.

As the North Vietnamese were pounding the south into submission with seemingly unlimited artillery it became clear that the village of Dong Ha was their strategic target. The bridge leading into the city provided the only way for the heavy T-54 North Vietnamese tanks to cross the Cam Lo-Cua Viet River in order to further exploit the south.

As a column of 200 North Vietnamese tanks and 30,000 enemy soldiers came rumbling down Highway One towards this tiny community, Colonel (at that time Captain) Ripley was given the sobering order to “hold and die.” Facing such superior numbers there was only one way out for him and his 600 South Vietnamese Marines. Lt. Col. Gerry Turley would be the one to give Captain Ripley the order to destroy the bridge but feared he was sending him to a certain death. Captain Ripley took a more philosophical approach.

“The idea that I would be able to even finish the job before the enemy got me was ludicrous,” Ripley said. “When you know you’re not going to make it, a wonderful thing happens: You stop being cluttered by the feeling that you’re going to [survive].”

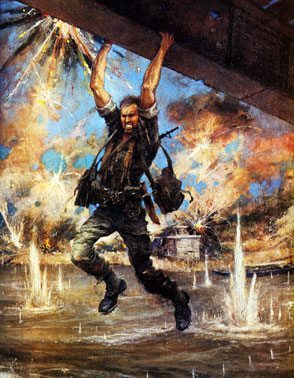

Blowing the bridge would not be easy. Captain Ripley had to place more that 500 lbs of explosives in the bridge’s underbelly. In spite of the fact that he had almost nothing to eat and very little to drink in days, he made dozens of trips between the river bank and the bridge with 40lb satchels of dynamite in hand each time. He then swung arm over arm clutching the I-Beam girders of the structure like a trapeze artist. Enemy fire from the opposite bank continually ricocheted around him as he strategically placed each satchel under the bridge.

When it came time for setting the explosives he realized he did not have the crimpers used to connect the percussion caps to the primer cord. Not allowing this to deter him he simply crimped the detonators with his teeth as he suppressed the horrifying thought that one wrong move would be sufficient to blow his head off.

It would take over three and half grueling hours to accomplish this task and with each trip out into the bridge he felt his strength fading and feared he might pass out.

“The only way I was going to be able to do this,” he said to an audience of TFP members, “was simply to ask God to come along with me.”

Marines are able to make it through physically demanding exercises, he said, with the use of rhythmic chants. He decided to use his own improvised Catholic version and began a continual ejaculation of, “Jesus, Mary, get me there!” They did in fact help him get there since he was ultimately successful in blowing the bridge and thwarting the plans of the Communist North Vietnamese.

Modern Day Knight

As impressive as this story is, Col. John Ripley was not well known outside of the Marine Corps for over a decade, until the release of John Miller’s book The Bridge At Dong Ha. The Naval Academy would eventually honor him with a diorama in Memorial Hall depicting his exploits at Dong Ha and his tale is now “required reading for every Naval Academy plebe.”

Col. Ripley would go on to receive the Navy Cross for his heroism along with numerous other awards. At the time of his death he was considered one of the most highly decorated Marines. Obituaries of the fallen hero used such words as “legendary.” What really defined him however, was something much larger than the numerous medals that adorned his chest; it was the chivalric spirit that burned in his heart. Col. Ripley was in many ways the embodiment of a modern day knight.

While speaking to a TFP audience about Vietnam he was brought to tears when recalling that among the civilians he saved in the village of Dong Ha, was a school full of innocent children. This tender solicitude for the weak and defenseless was an essential characteristic of the medieval knight but one that is often overlooked when exhibited by an American soldier such as this. A man like Col. Ripley who had seen the worst side of human nature and the most violent aspect of war never lost a tender side capable of caring for the “little ones.”

The ferocity with which he defended the village people of Dong Ha was also unleashed in defense of womanhood in America. On June 26, 1992, shortly before his retirement from the military, Col. Ripley waged what could be considered an assault against the politically-correct idea of sending American women into the hostile and often filthy environment of combat.

He began his testimony before a Presidential Commission with a sagacious affirmation that the issue should not be “argued from the standpoint of gender differences.” Many had argued, and still argue this contentious question on the basis of equality. Col. Ripley, in the fashion of a true knight, called for the protection of “femininity, motherhood, and what we have come to appreciate in Western culture as the graceful conduct of women.”

In the following year Col. Ripley took an even more courageous stance when he testified before the House Armed Services Committee against homosexuals in military during the hearings that preceded the implementation of President Clinton’s “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

This could have been the thing which led retired General Thomas L. Wilkerson to give probably the best worded eulogy of this true American hero.

“I admired John”, he said, “not only because of his obvious war heroism, but because of how he conducted himself after the war. John was the standard to which we all aspire.”

Angels and Toy Soldiers

In reflecting on such a great man I could not help recall something I noticed during a visit to Col. Ripley office many years ago. It was a seemingly insignificant decoration that seemed to define the man. Sitting next to his desk was a decorative drum which looked like it a might be a reproduction of the Revolutionary war era. I regret not asking him about it when he was alive. Not because of the historical significance of the instrument but because of what he had on top. It was a little battalion of tiny lead soldiers in magnificent uniforms, neatly arranged in battle array, marching across the skin of the drum.

It is not uncommon for little boys to play with toy soldiers. Perhaps it is their way of projecting themselves onto an imaginary battlefield where they can fight for noble ideals. It did seem to be a significant, though not surprising, choice of decoration for the office of a seasoned warrior like Col Ripley. He was, after all, a man who appeared to retain much of his childhood innocence.

The toy soldier collection in turn reminded me of a story I heard him tell of Sister Patience who taught him catechism as a boy. She used to tell the students to leave part of their seat for their guardian angel to sit down. With an innocent chuckle, that was so much a characteristic of Col. Ripley, he described the amusing scene of a classroom full of children sitting on half a seat. Unlike the majority of men of today, however, there was not an ounce of cynicism in this description. He believed in the presence of angels as much as he did Our Lord and His Mother, who helped him in that desperate situation so long ago.

Col. John Ripley was a true warrior, a modern day knight and a chivalrous gentleman who never allowed a cynical world to cloud his boyhood dreams nor tarnish his innocent desires. He will be sorely missed.

Click to Order your copy of Norman Fulkerson’s book An American Knight: The Life of Colonel John W. Ripley USMC. Also available is an e-book.