There is something about toy soldiers that brings out the boy in every man.

There is something about toy soldiers that brings out the boy in every man.

Before toys became genderless and pacifistic, the toy soldier was the mainstay of countless boyhood games. How many boys marched their soldiers into battle, staged mock wars, and dreamed of military glory! Indeed, how many military careers were born on the humble battlegrounds of living room floors.

My thoughts were far from such childhood musings when I approached Brown University’s library in Providence, Rhode Island. At the entrance, I chanced to see a sign mentioning the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection on the fifth floor.

Intrigued, I walked up the flights of stairs and down the hallway. Upon reaching the door, I rang the bell. The librarian, a military researcher, craned his neck out, asked what I wanted, and then let me in.

Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine what I would find. I had stumbled upon America’s foremost documentary resource of soldiers and soldiering, one of the world’s largest collections devoted to the study of military uniforms — and a wonderland of toy soldiers.

How did such a military collection end up on a liberal American campus? Only in America can you find such a paradox.

A Wonderland of Soldiers

There they were: toy soldiers, thousands of them, all in brilliant, colorful uniforms. In lighted vitrines, display after display of military toy soldiers in battle array represented fighting men and their units from the days of ancient Egypt to the twentieth century.

There were Egyptian chariots, Roman legions, and Persian armies. There were exquisitely detailed medieval knights on horseback and displays of Renaissance armor. There were Gordon Highlanders, Irish Guards, the Black Watch, and the most celebrated regiments of Britain and France. I marveled at glamorous nineteenth-century uniforms of every nationality with all their splendor and display.

I also found familiar historic figures. There were Charlemagne, Saint Joan of Arc, and famous crusaders. I saw others ranging from Louis XIV to Robert E. Lee to Churchill. It was a veritable procession of history.

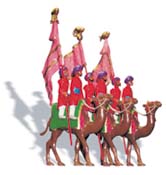

It did not stop there. Amid the 288 feet of displayed soldiers, I found turbaned Indian troops on elephants, robed Bedouins on camels, bandoliered Boers, and rampaging Zulus.

in a gilded carriage surrounded by Swiss

and Noble Guards

Finally, there was a host of displays of military and royal pomp and circumstance. Not least among these was a spectacular English coronation with all its splendor. But above all, I could not contain my enthusiasm for the scene of a papal parade, featuring the Vicar of Christ in a gilded carriage surrounded by Swiss and Noble Guards.

I was spellbound. Like a young boy reliving battles past, I spent the next two hours in awed wonder.

A Vast Collection

The next day I returned to find out more about this extraordinary collection. Library curator Peter Harrington was only too happy to answer my questions.

I learned that the collection contains more than just toy soldiers. Presently, there are over 12,000 printed books, 18,000 albums, sketchbooks, scrapbooks, and portfolios, and over 13,000 individual works of art dedicated to military themes.

To my surprise, I also learned that the library was the life-work of one person. And that person was an extraordinary lady.

The Extraordinary Mrs. Brown

Anne Seddon Kinsolving was born on March 25, 1906, in Brooklyn, New York. Her parents were both members of the Virginia aristocracy with impressive lineages. Her father eventually became rector of Old St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in downtown Baltimore where she spent her childhood.

From her earliest days, Anne developed a penchant for all things military. She traced this love to a treasured copy of The Wonder Book of Soldiers for Boys and Girls given to her on her ninth birthday. She was also impressed by the parades and uniforms she saw in Baltimore during World War I.

In 1930, she married John Nicholas Brown, heir to one of the oldest fortunes in America. During their honeymoon in Europe, the new bride decided to buy a “few” toy soldiers to decorate a room in their home in Providence. Those few soldiers became a veritable army.

Beginning of a Collection

Mrs. Brown was not the type of person who was content to own these soldiers; she wanted to identify and know them. She embarked on a quest to catalogue her troops, concentrating on those from the seventeenth century onward. With great energy, she contacted booksellers on military costumes in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and other major cities, and she herself made numerous sorties into the backrooms of those shops in search of prints, drawings, and illustrated books. She also wrote books on military subjects and beca a leading authority on military collections and uniforms.

Not satisfied with the domestic market, Mrs. Brown made forays overseas and soon began acquiring books and prints from all over Europe. When World War II broke out, a bomb fell on Ackermann’s, a major military publisher in London. That incident spurred her into launching an extensive importing operation, giving her agents carte blanche to buy any military art to save it from the ravages of war.

The postwar years saw her broadening her collection with further acquisitions. According to Mr. Harrington, however, she made little effort to collect modern khaki uniforms because their egalitarian design was drab and “there was little difference between the soldier’s and officer’s uniforms.”

Wanting to organize her collection better, she eventually hired a full-time librarian, who arranged it in its present form. The collection outgrew the Brown’s home and by the time of her death in 1985 the whole collection had been gradually transferred to Brown University library, where it remains as a legacy to her passion.

An Attraction to Heroism

The fascinating story of Mrs. Brown is but part of the story of her toy soldiers. I asked Mr. Harrington what had attracted her to them, and he responded that it was something more than just an eccentric fancy.

Mrs. Brown had noted that the picturesque beauty of the uniforms themselves is not what leads men to honor the soldier. Actors and acrobats, she observed, can be equally picturesque.

No, what attracts us is a higher ideal symbolized in these men in uniform. There one sees expressed the moral beauty inherent in military life: the elevation of sentiments, and the willingness to shed one’s blood for a higher cause. One sees the strength for undertaking, for suffering, risking, and winning.

The beauty of the military uniform speaks of the moral nobility of a fight that is entirely based upon ideas of honor, and of force placed at the service of good and turned against evil. It is the joy of serving with courage, strength, discipline, and heroism that allows the soldier to live in an atmosphere of legend and glory. It is only right that the uniform express these values with color, pomp, and ceremony that attract the multitudes.

Alas, such sentiments find little sympathy in the postmodern man who puts no ideal above self. Today’s pacifists hold an erroneous idea of peace whereby conflict must be avoided at all cost, even at the sacrifice of principles. This is not true peace, but the stagnant “peace” of moral decay.

True peace, as Saint Augustine teaches, is the tranquility of order, above all Christian order. In this, peace is a fruit of an order that must sometimes be defended. And soldiers have sacrificed themselves from time immemorial so that people can have this true peace.

That is why their legends live on — even in the toy soldiers who depict their deeds.

When asked during a speech she gave in 1961 why so many people have portrayed the soldier, Mrs. Brown quite aptly replied: “I prefer to believe it was because, as men, they were admired and respected, even when they were feared, and that over the years the men who themselves had no urge to pioneer and endure the heat of battle, the artists and poets and composers, felt in their hearts a debt of gratitude to the military men who have earned them the privilege of living in peace. So they made these men immortal.”

You can visit the Military Collection at Brown University.