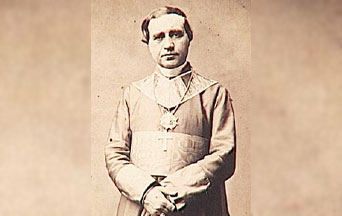

During the Second Empire, some in the Catholic movement unfortunately decided to collaborate with Napoleon III’s policy of favoring Italian revolutionaries. They went so far as to oppose the Holy See openly. These figures included Catholic republicans and ultra-Galicans, of whom Bishop Henri Louis Charles Maret 1 was the most outstanding representative.

In 1857, they constituted only a tiny fraction of Catholic opinion. After many failed attempts to rally Catholics around his government, Napoleon III was obliged to enlist the help of Bishop Maret. The Emperor could not count on Louis Veuillot’s Ultramontanes or liberal Catholics. Veuillot defended the rights of the Holy Father uncompromisingly, while liberal Catholics fought against the empire for political reasons.

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

During the time of Louis Philippe, Henri Louis Charles Maret, soon after his 1830 ordination, became a professor at the Sorbonne. He was the Dean of Theology and held the post until the end of his life in 1884. After the 1848 revolution, he became a republican extremist and companion of Frederic Ozanam and Fr. Jean-Baptiste Lacordaire in their short-lived liberal newspaper, L’Ère nouvelle. His extreme opinions frightened even Lacordaire, who abandoned the newspaper. Father Maret remained at its head until it disappeared.

With the advent of the Second Empire (1852-70), Father Maret saw that Napoleon III kept the democratic virtues of the Bonaparte family and became one of his greatest defenders. His friend, Father Pirre-Louis Coeur, had identical views. In 1849, Father Coeur became the bishop of Troyes. In 1853, the government made Father Maret dean at the Sorbonne, and he was later appointed the titular Bishop of Sura in 1861.

The orientation of these two churchmen was absurdly Gallican and pro-government, and they only deserve mention because they show well the final consequences of so-called liberal Catholicism. The liberal Catholics, especially Bishop Felix Dupanloup of Orléans and the Correspondant group, strove to avoid adverse consequences through skill and contradictions. In contrast, the letters that the two prelates wrote to Gustave Rouland, Minister of Education and Religious Affairs, show how Louis Veuillot and l’Univers occupied a prominent position in the Catholic movement.

For Bishop Maret, the Church was divided into two parties: ultra-Catholics and prudent or moderate Catholics. At the same time, he saw Minister Rouland as “a man whose lights, doctrines, and character mean he will take care of the vital interests entrusted to his care with the noble aim of reconciling the true principles of modern civilization with the eternal truths of which Christianity is the depository.”

In a memorandum to Minister Rouland, Bishop Maret described the ultra-Catholic party.

“This dangerous party possesses, however, considerable organization and power. It is headed by bishops commendable for their knowledge and virtues. These bishops have at their orders talented ecclesiastical and lay writers; their mouthpiece is a newspaper often written with verve and wit; they form a large part of the lower clergy.”

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Learn All About the Prophecies of Our Lady of Good Success About Our Times

Later, Bishop Maret described them in more detail.

“But I have not yet unveiled their main strength: it is not in France but in Rome. That is why the ultra-Catholic party is the defender of the temporal and spiritual dictatorship of the Sovereign Pontiff. It exalts Rome’s recommendations and entire past; all dreams, interests, and passions stirred there. For its part, Rome accumulates favors from the bishops who lead these parties, encourages their writers, defends their newspapers, and puts the Congregation of the Index at their service.”

The two bishops were not always so restrained in their language. In 1862, Bishop Maret promoted the appointment of Bishop Coeur to the then-vacant Paris Archdiocese. However, the government did not intend to go that far to support its allies, who represented a very small part of Catholic opinion. Again, Bishop Coeur displayed his overweening pride when he wrote Minister Rouland.

“As long as the Index and Inquisition decrees are freely published, as long as our Church’s ancient and traditional rules are not re-established, this poor prelate nominated to such dignity will only be the executor of the plans of cardinals at the Univers. I will not submit myself to such humiliation.”

Naturally, Louis Veuillot was the main target of the memoranda the two bishops addressed to the government. Their reports consistently called for the empire to resist Rome and combat l’Univers. They claimed that the Holy See and l’Univers wanted papal absolutism, clerical domination of the temporal sphere, a theocratic regime, the social order of the Middle Ages, and everything anti-modern, anti-French and anti-Napoleonic. They charged Veuillot with being an enemy of the Revolution, claiming that he condemned the principles of 1789, the constitution of 1852, and the empire itself. He was dangerous because l’Univers influenced public opinion. They made the absurd claim that Veuillot had “thirty secretaries, mostly priests.”

10 Razones Por las Cuales el “Matrimonio” Homosexual es Dañino y tiene que Ser Desaprobado

Bishop Maret ended one letter to the minister this way: “Such are the doctrines he advocates and the spirit he instills in his disciples. His intentions may be loyal, and his sympathies are very pronounced. But his spirit is essentially hostile to the significant interests which the imperial regime represents and protects.” Upon reading that letter, Bishop Coeur hastened to congratulate his colleague. “It was God who inspired you when you wrote to the minister. What a danger this fanatical newspaper represents!”

Beneath the surface, the government deemed the two bishops quite troublesome. Their adherence to the empire was fanatical and could occasionally disrupt the Emperor’s policy. However, they were often useful. Bishop Maret became one of Napoleon III’s mainstays in the struggle against the Holy See. He did not hesitate to applaud the Emperor’s policy toward the Italian revolutionaries and, later, wrote a book against papal infallibility.

Photo Credit: Rvalette –Wikimedia Commons

Footnotes

- Henri Louis Charles Maret was the Dean of Theology at the Sorbonne from 1853-1884. In 1860, the government appointed him the Bishop of Vannes, but Pope Pius IX blocked the appointment. Maret was appointed the titular Bishop of Sura in 1861 and the titular Archbishop of Naupactus in 1882. In 1869, he wrote Du concile général et de la paix religieuse, which opposed a definition of papal infallibility and stressed the place of bishops in the Church’s constitution. In 1870, he was a council father at the Vatican Council.