Michael Drake: What is the significance of the natural moral law for a secularized country?

Michael Drake: What is the significance of the natural moral law for a secularized country?

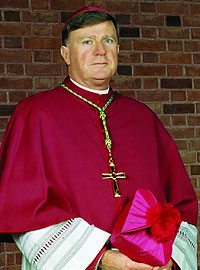

Bishop McManus: The recognition of a natural, moral law provides the common ground between believers and non-believers about the fundamental moral issues affecting the common good and our living together.

In a morally relativist society like the United States, we have people who have reduced moral positions into personal opinions. Once my opinion differs from your opinion, the conversation breaks down.

If I appeal to Divine Revelation, whether Old or New Testament, a non-believer would say, “That is very nice for you, but I do not believe in that.” Thus, the conversation stops. However, when we both believe we share a common human nature that contains in itself fundamental inclinations geared toward fulfilling what it means to be human, we can talk. We can agree that it is necessary to reflect on these fundamentals, so as to encompass some type of moral position. From that disciplined reflection, we have a common language in terms of trying to work and live together in a morally acceptable way.

Michael Drake: So, it is an appeal to the human condition of that person?

Bishop McManus: It appeals to the fact that we have something in common, which is our human nature.

Another reason for retrieving the natural moral law tradition is that there are so many competing ideas of what it means to be human in our society. Because of our Faith, we have what we call a Christian anthropology or a Christian way to look at what it means to be human, because we look at our humanity through the light of Divine Revelation.

I think much of our moral discussion breaks down because people are working out of various anthropological visions—their understanding of what it means to be human. If we appeal to natural moral law, even before we get into that discussion, we raise the issue and put ourselves in a position to say: “Let us sit down and talk about what you think it means to be human. What do you think it means to act in a humane way?”

Michael Drake: What is the role of the Catholic laity in defending and promoting the natural moral law? Where have the faithful been successful or helpful in a special or significant way?

Bishop McManus: First of all, we can apply this to our personal lives. Living in the midst of our religiously pluralist and morally irreligious society, we Catholics sometimes get the feeling we are very strange people who believe certain things about moral living that no one else does. However, if we become acquainted or re-acquainted with the natural moral law position, we would realize that the Catholic position is not sectarian or private. While our position is buttressed and supported by our faith in Divine Revelation, fundamental Catholic positions on morality are derived from human reason, reflecting on human nature, which is, in fact, the natural moral law.

Secondly, if we seriously believe that the primary role of the laity is to transform society and to bring Gospel values and Church teachings to the public square, then, in a religiously and morally pluralist society, knowledge of natural law allows our Catholic laity to enter the public arena and involve themselves in public policy issues, using a language that is non-sectarian and non-theological, but is commonly shared by people, simply because it is a natural language.

Michael Drake: In the issues that are coming down the pike at us—cloning, harvesting human organs, and the redefinition of death to incorporate the new technologies to allow us to use the vital organs—do you have any comments on the natural moral law from the perspective of bioethics?

Bishop McManus: If in the pursuit of retrieving natural moral law in terms of moral reflection, we can refocus on what it means to be human, then the way we treat the disabled, no matter how old, sick or challenged, determines their dignity as a human person. Whether challenged, limited, or debilitated, the disabled are still human, and part of being human is that you do not destroy yourself or others. Hence, the natural moral law condemns euthanasia or assisted suicide.

Michael Drake: It’s hard to portray the natural moral law in an image. Archbishop Chaput brought up the civilization’s problem of the image with that famous picture from a magazine of the zygote on the end of a needle. It doesn’t look human, so it is not being treated as a human being. How can we overcome that image?

Bishop McManus: Again, we return to what it means to be human. Humanity is not exhausted by our ability to sense things. A fundamental part of being human is the use of intelligence. We can reflect on issues and go beyond what is immediately available by the senses. The senses, obviously, are used in the process of knowing. Sensation is fundamental. However, there is more than what meets the eye. That is certain in the case of the development of human life. Although the embryo is microscopic, it is still a real human life.

Michael Drake: So we appeal to the rational nature of man?

Bishop McManus: Yes, exactly.

Michael Drake: Thank you very much for your time, your Excellency.

Bishop McManus: Very good. Nice being with you.