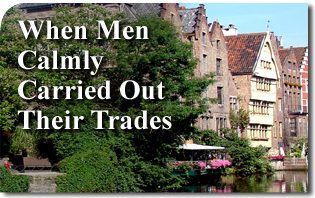

In the placid waters of this canal of the Belgian city of Ghent, the facades of some buildings typical of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance have been reflected for centuries. These buildings create a singular architectural impression of balance because of the harmonious contrast between their imposing, serious and solid mass, and the rich, varied and almost dreamlike decoration on their facades.

Eternal and Natural Law: The Foundation of Morals and Law

What was the original use of these buildings, which are so recollected that we would call them almost pensive? Were they the houses of patricians? Study centers? No. They were used by trade associations. On the far right can be seen the corporate headquarters of the Free Boatmen. Next is the center for Grain Measurers and a small Customs building where medieval merchants came to declare their goods. Then comes the Barn, and finally the offices of the Guild of Bricklayers.

Thus, these were buildings for work and business. And history tells us that a most intense and productive trade went on inside them.

However, at that time, economic production was still not affected by today’s materialistic influences. Work took place in an atmosphere of calmness, thought and fine taste, and not in the feverish, frantic, thoughtless and proletarian atmosphere that so often marks our days. Who could suspect so much nobility and good taste in these bourgeois buildings destined for guild work?

This is not a matter of taste but rather a question of mentality. According to a conception of life that gives value to spiritual things, the best course of human action is guided by the mind. Thus the quality and even the quantity of economic output is best when it takes place in a calm atmosphere without idleness and with meditative recollection.

On the other hand, the materialist conception values quantity over quality; body over soul; agitation over reflection; and nervous hyperexcitement over authentic thought. That is why we see the vibrant atmosphere of certain stock markets or large modern thoroughfares.

* * *

A climate of hyperexcitement reflected its cause: the agitation inside man. The image of the businessman that chews gum, chomps on his cigars, perhaps bites his nails, stomps his feet on the ground, is known to all. He is hyperactive, cardiac, and neurotic.

How different are the placid, stable, dignified, prosperous and intelligent-looking merchants in the admirable painting from the brush of Rembrandt: “The Syndics of the Cloth Merchants’ Guild.”

It was men like these who, with the communications media still uncertain and slow, extended their network of activities in all directions and laid the foundations of modern trade. However, their work took place in tranquility, and we would almost say recollection. They also reflect the particular atmosphere of the old buildings that we analyze.

This is a fecund lesson for our poor world, increasingly ravaged by neuroses.

Originally published in Catolicismo, No. 92 – August 1958, in the series “Ambiences, Customs, Civilizations.” It has been translated and adapted for publication without the author’s revision. –Ed.